THE LIARS OF NATURE AND THE NATURE OF LIARS

LIXING SUN

The Liars of Nature and the Nature of Liars

CHEATING AND DECEPTION IN THE LIVING WORLD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2023 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number 2022948596

ISBN 978-0-691-19860-6

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-24573-7

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Alison Kalett and Hallie Schaeffer

Production Editorial: Jill Harris

Text Design: Heather Hansen

Jacket Design: Heather Hansen

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Sara Henning-Stout and Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Susan Matheson

Jacket image: Leaf mimic katydid (Family Pseudophyllidae), Morley Read/ Alamy Stock Photo.

For Shine and Orien

and their world in the future

CONTENTS

THE LIARS OF NATURE AND THE NATURE OF LIARS

CHAPTER 1

Liar, Liar, Everywhere

She is pregnant. Raising a child takes a lot of time and energy, yet she is short of both. Homeless, she has no choice but to find somebody else to take care of her babyfor free. Its not easy, but she knows how to pull it off. She scouts around and spots a cozy house in a quiet neighborhood. The young wife of the family looks caring and has just given birth to a new baby, so is a perfect choice as a surrogate. She hides herself and waits in the vicinity, keeping watch on the house. Opportunity presents itself when the new mother takes a short trip to get some food. She sneaks in and switches the baby with her own. Then she heartlessly throws the victims infant in a dump.

What you have just read is a cold-blooded murder case, one that takes place in nature when a female cuckoo bird sneaks her egg into a warblers nest. The cuckoo is cheating, though the scenario doesnt quite fit Oxford English Dictionarys definition of the verb cheat: to act dishonestly or unfairly in order to gain an advantage. Cheating in humans usually involves an element of intention. In the larger biological world, however, establishing intent is neither easy nor necessary. For biologists, as long as organisms act to favor themselves at the expense of othersespecially in situations when cooperation is expectedthey are cheating.

This book is about the behavior, evolution, and natural history of cheating. Although, in common usage, the word cheating is often interchangeable with lying and deceiving, the three words differ in connotation, nonetheless. Furthermore, lying and deceiving involve two very different biological processes, as we will unveil in the next two chapters. In light of this new insight, the word cheating refers to both lying and deceiving in the book.

Cheaters are everywhere in the biological world, according to our broadened definition of cheating. Monkeys sneak around for sex; possums, well, play possum, as they are famous for when pursued by a predator; birds scare rivals away from contested food by crying wolfemitting alarm calls that are normally used to warn others about an approaching predator; amphibians and reptiles are master impostors, altering their body color to blend into their backgrounds; stickleback fish protect their eggs and babies by misdirecting their cannibal peers away from their nests; defenseless caterpillars ward off predators by masquerading as dangerous animals such as snakes with big false eyes (see ); squids escape from predators by ejecting ink to create a smoke screen in the water. Examples of lying and deceiving behavior in animals can go on and on.

What may surprise you is that cheating doesnt require a brain, or even a neuron, as many plants are cheaters as well. For example, most orchids mimic the aromas of their pollinators food. Around 400 orchid species, however, evolved a more audacious tactic: they fool male pollinators by mimicking the smell and appearance of female insects to take advantage of eager males who seek opportunities to mate (see

Fungi cheat too. For example, trufflesmushroom-like species that form fruiting bodies undergroundemit a steroid called androstenol that mimics the pheromone of wild boars. Androstenol is produced in the testes of adult boars and has a musty odor to the human nose. When female pigs sense the truffle aroma, they will dig exuberantly for the source. What they dont know is that they are being suckered by something bearing no resemblance to the swine beau they are hoping for. The only outcome of their passionate fervor is spreading spores for the truffles.

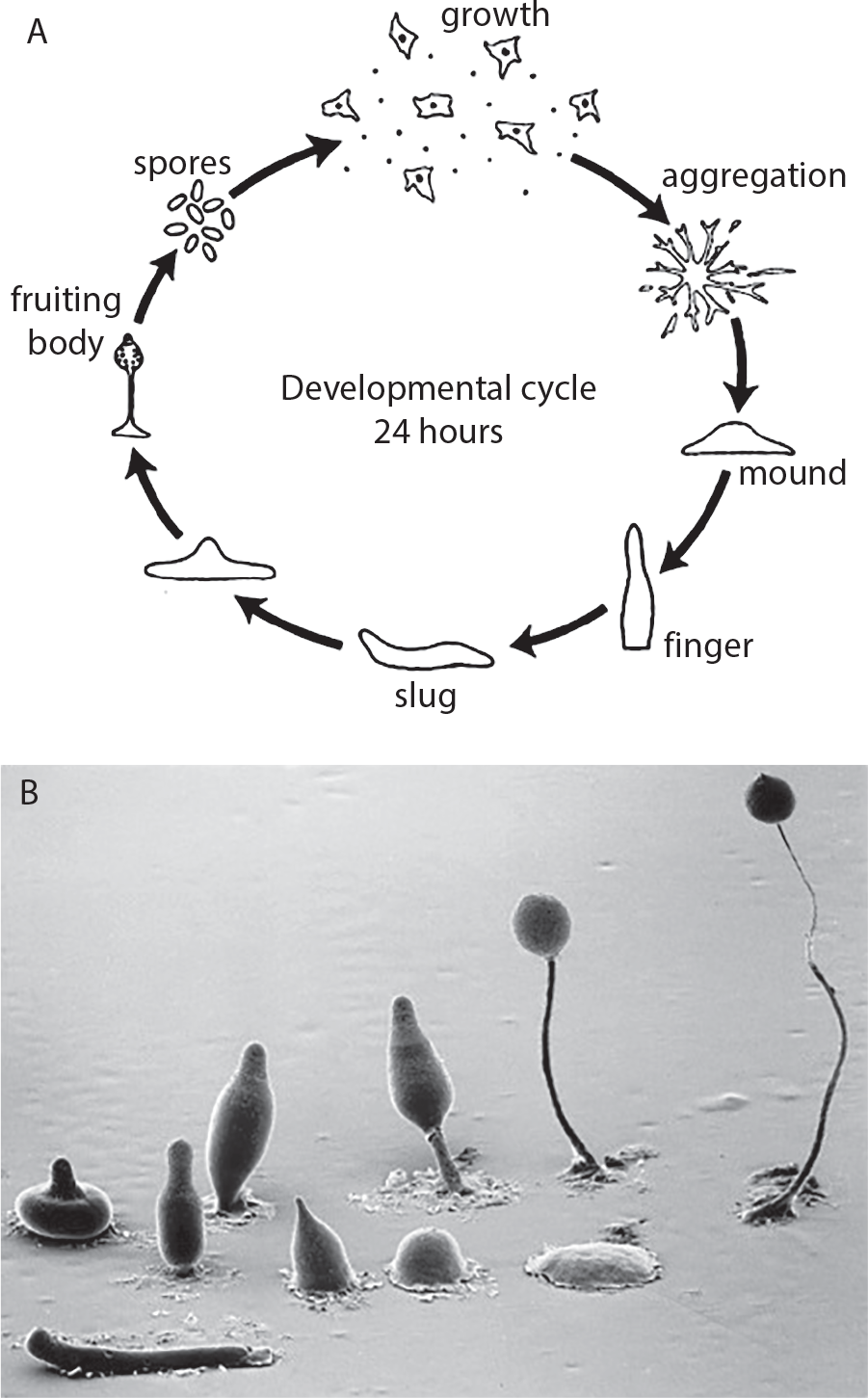

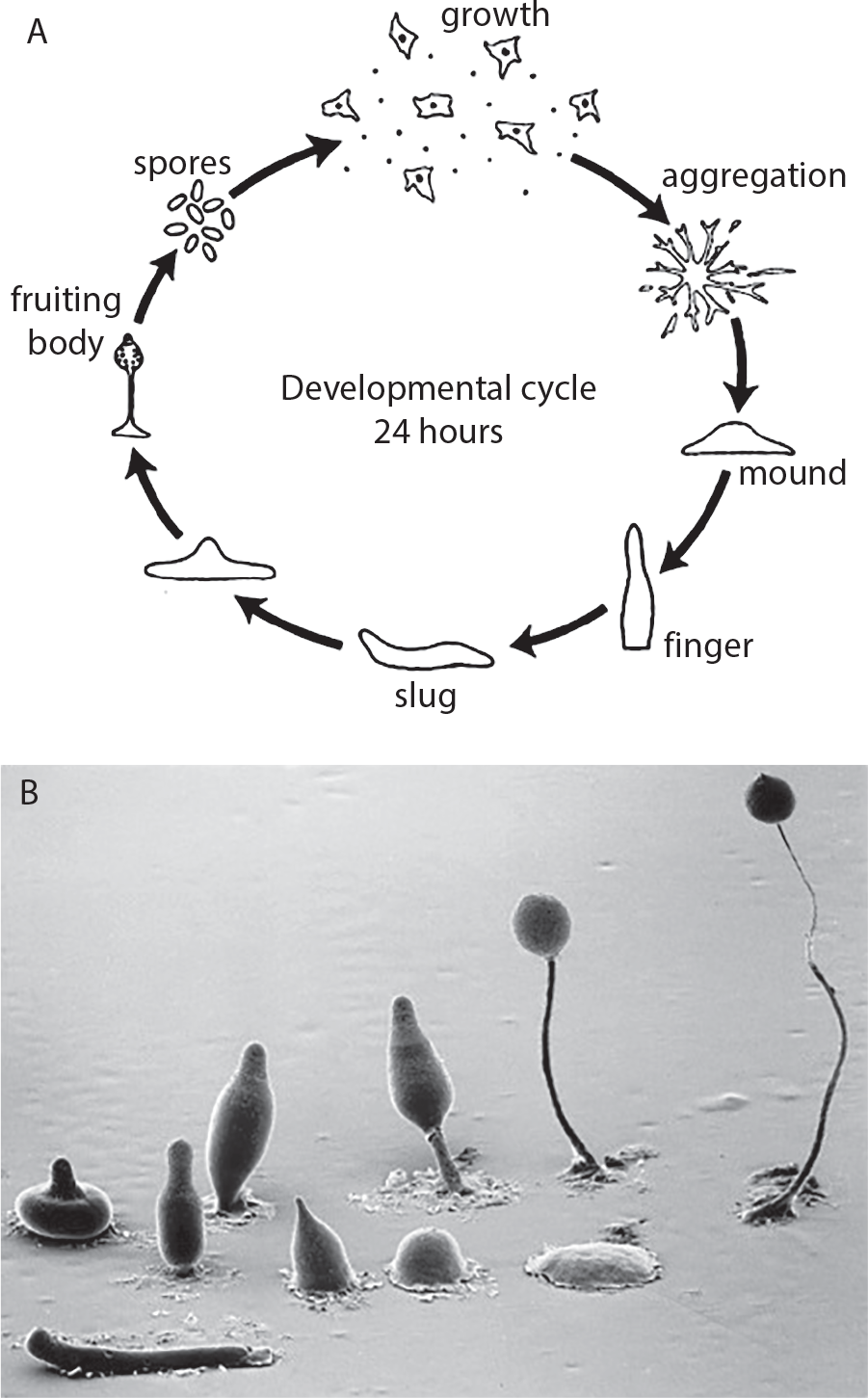

Complex organisms such as plants and fungi cheat; so does single-celled life. A good example is the slime mold (or social amoeba) known by its scientific name, Dictyostelium discoideum (or Dicty for short). When starved, the slime mold amoeba cells gather together to form a mobile, slug-like structure. The slug moves as a unit until it finds a suitable spot and then grows into a fruiting body made of a spore-producing head mounted on a thin stalk. The entire thing is shaped like a lollipop or a maraca (a rattle-like percussion instrument popular in Latin America) (). The cells in the head, which consists of 80% of all cells, will seed the next generation when food becomes plentiful again. The other 20% of the cells consigned to the stalk, however, rot away after completing their missionto raise the head so that the spores can scatter far and wide, like dandelions spreading their fluffy seeds in the wind.

If you were a slime cell, where would you prefer to end upthe head or the stalk of the fruiting body? The head, of course! Because only in the head do you have the opportunity to pass your genes to the next generation. If you were a cell in the stalk, your genes would be destined for an evolutionary dead end. Who, in the biological world, wants to be relegated to an inferior status, without a chance to reproduce?

Fortunately, this isnt a major issue when amoeba cells have the same genetic makeup, like identical twins. When cells share an identical set of genes, it matters little as to which cells seed the next generation. However, when a fruiting body is made of a chimera of two or more types of cells, where many of the genes are different, conflict ensues. They all compete to be part of the fertile head rather than play a supporting role in the sterile stalk. As one might expect, different cells play dirty in order to make it into the prized head by any means necessary, including cheating.

FIGURE 1.1. The developmental cycle (A) and sequence of spore formation (B) in the social slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum (Myre 2012).

Next, lets visit the bacterial world to see whether they also cheat. Bacteria are tiny. Individuals alone cant do much. Just as building the Great Wall involved hundreds of thousands of humans, achieving collective bacterial tasks (such as emitting lightbioluminescenceand trapping vital elements from the environment) requires millions of bacteria working together toward a common goal. Thats why bacteria often congregate to form a thin, slimy layer called biofilm in soil or water.