Dedicated to Z.

CONTENTS

The New Deal has restricted the hours of labor and thereby has introduced a tremendous amount of New Leisure.... Sooner or later this Niagara of leisure will have to be absorbed.... A large part will be devoted to such electronic entertainment as radio, sound-pictures, home talkies, phonograph reproduction, synthetic musical instruments, and eventually, television.

Electronics magazine editorial, September 1933

E ngineers of the early twentieth century held an invisible new power in their hands: they could control the flow of electrons. Harnessing electrons to serve human purposes was a technological leap that would change the shape of the century. Radio would be the first worldwide application of this new power, followed by television and later telecommunications and computer networks, with a thousand smaller steps in between. Todays micro devices, tucked imperceptibly into our bodies and our personal tools, are the direct descendants of those discoveries.

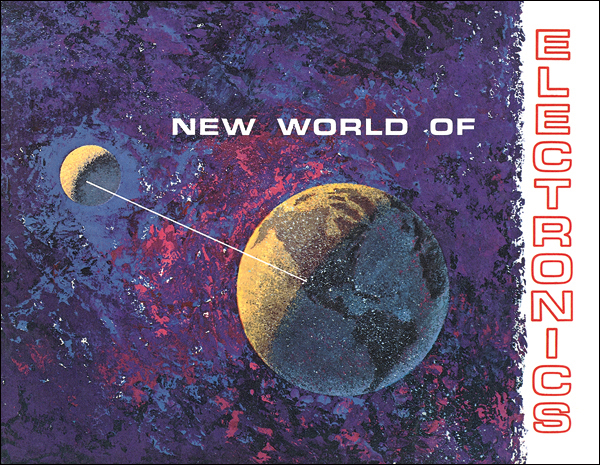

Todays cloud computing facilities actively defy their physicality, while the smallest devices have shrunk to the scale of the electron. Computing culture embraces not-being-seen. In contrast, for most of the twentieth century electronics were new devices that benefited from visibility. The component parts of electronic devicestubes, transistors, and circuitswent through a bell-shaped cycle of emergence: they became steadily more widely seen from the 1910s through the 1930s, then popular and familiar in the 1940s and 1950s. One by one, components entered the public stage and took their places as new artifacts in the cultural firmament.

The devices that they made possible, such as radio, television, and computers, led the visibility of electronics. But the emergence of components had more in common with the systems that those components enabledtelecommunications, transportation, and information. Components and systems both developed outside the view of most people who would use them. In order for them to be introduced and understood, they were placed at the center of advertising and literature campaigns that drew on the talents of graphic artists to convey otherwise invisible developments. The large mainframe computers of the 1960s were the turnaround point of these campaigns for visibility. From the 1960s onward, electronics shrank in size and retreated from view, heading toward todays invisibility.

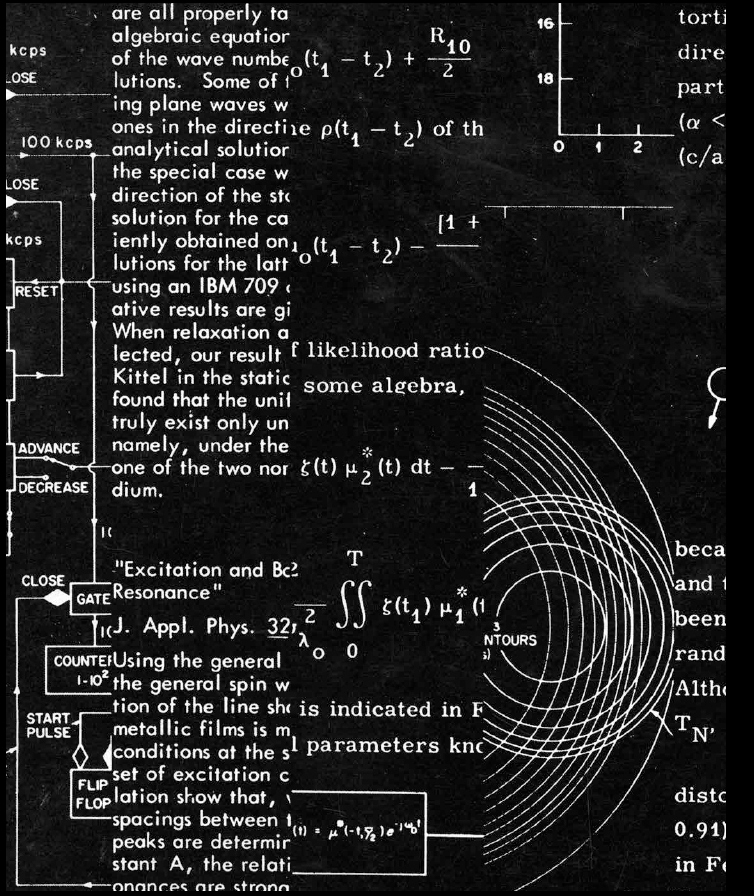

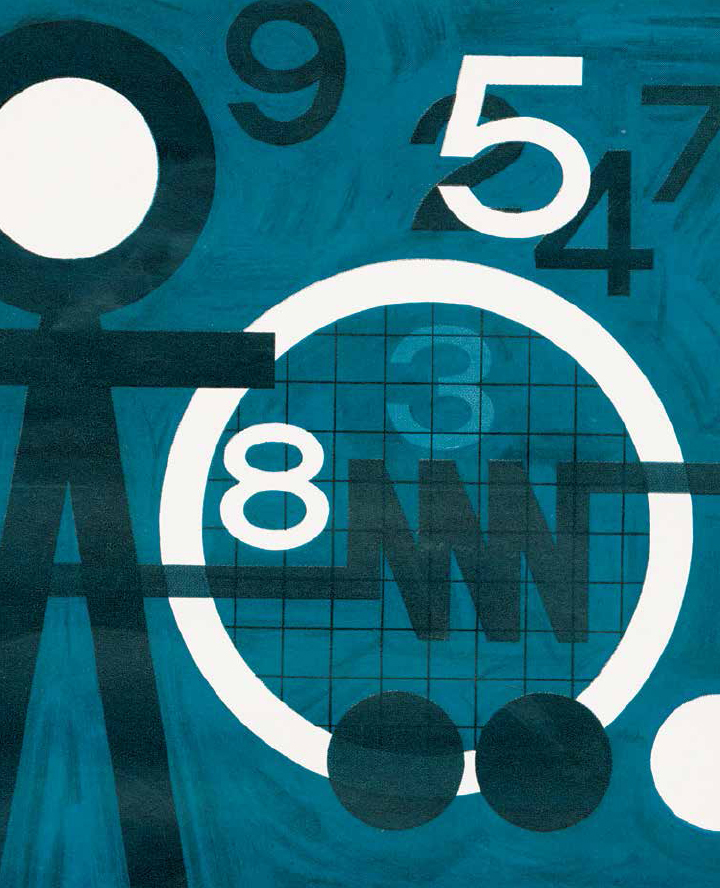

Fig. i.1: THE ELECTRON AND THE SOLAR SYSTEM. GENERAL MOTORS BOOKLET, 1964.

That this period of visibility happened is remarkable. Components themselves were not marketed to the general public, neither were computers in their early decades. The flow of electrons could not be seen, nor could anything as abstract as the process of computation or the emergence of information systems. Each component was a successive invention that emerged from a laboratory and from there became part of a closed system. They reached our pockets and living rooms when they became parts of a new whole: the new radio! the new TV! Yet they did come to light, made vivid on the pages of magazines, catalogs, and books aimed at a techno-savvy readership. The medium of their reveal was art made for industry; the result was a dramatic intersection of art and technology.

This book is a history of electronics that explains technology through the lens of art. It also asks the question: What cultural history of electronics can be extrapolated from a close look at the associated commercial graphic art? The result is a guided tour through the commercial and advertising art that was created when the labors of engineers met the inspiration of artists. At its heart is a technological story of the development of electronic components from laboratory to tabletop. The medium of exploration is the artwork through which new components were introduced, contextualized, and promoted. Whats revealed is arts ability to touch the intangible and render it visible.

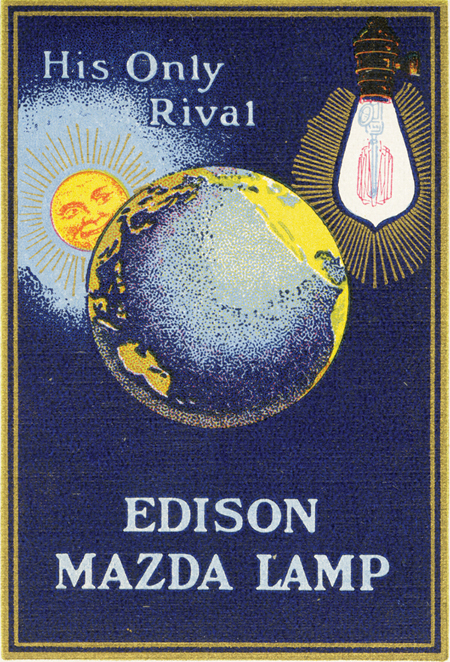

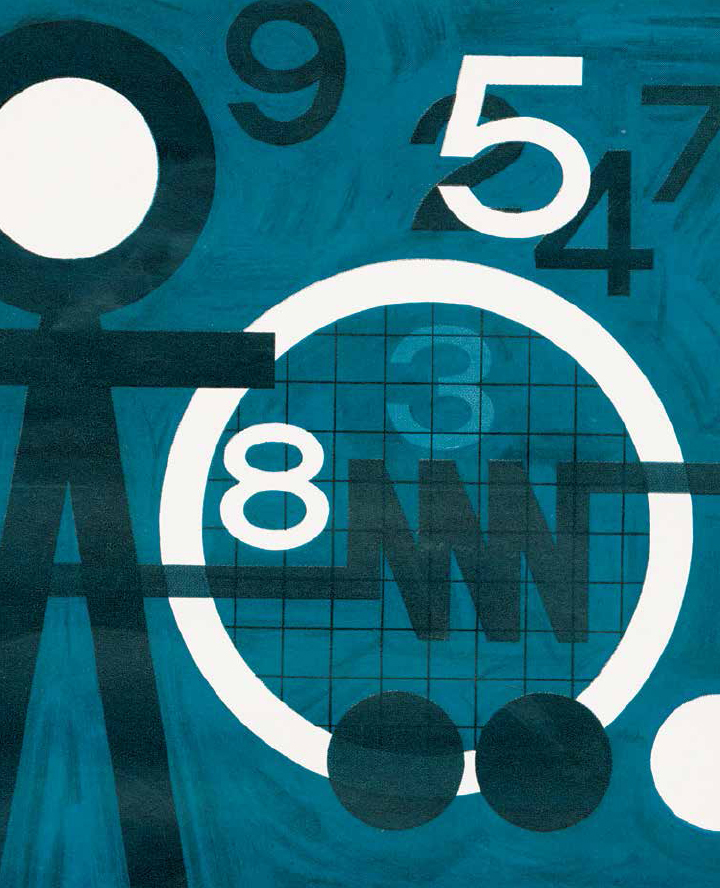

Fig. i.2: ELECTRICITY AND THE SOLAR SYSTEM: THE ARTIST MAXFIELD PARRISH CREATED AN AD CAMPAIGN FOR GENERAL ELECTRIC IN 1917 TO PROMOTE THE COMPANYS EDISON MAZDA LAMP BRAND.

COMMERCIAL ART FOR THE ELECTRONICS INDUSTRY: THE FIRST FIFTY YEARS

The printed literature written and illustrated in the mid-twentieth century to explain electronics provides the raw material for this book. These documents, made primarily for industry and secondarily for the general public, are part of a long tradition of commercial art that stretches back to nineteenth-century lithography. The discipline of graphic artart created for reproductionhas its origins in the printing boom of the nineteenth century. Early twentieth-century commercial art was a fertile ground for the lush illustration of the brand-new hardware of everyday life, such as the lightbulb.

The mid-century era of this book followed directly from the preceding fifty years of invention and illustration. The humble lightbulb stepped into that tradition when it hit the market in the 1880s. It was the first mass-marketed electrical component. As a stand-alone invention it became the subject of artistic attention, sponsored by manufacturers, to introduce, promote, and contextualize it for the public. The synchronous development of the telephone was a similarly tangible outcome of the new-found ability to control electricity within circuits. The respective laboratories of Alexander Graham Bell (later, AT&Ts Bell Telephone Laboratories) and Thomas Edison (whose Edison General Electric company became General Electric) were neighboring epicenters of discovery in methods of harnessing and applying the power of electricity. GE commissioned the noted illustrator Maxfield Parrish to create a series of promotions for the companys Edison Mazda lamp (a lightbulb); fig. i.2 is one of many results. The slogan His Only Rival (referencing the sun) promotes the bulb in distinctly planetary terms. Both this image and fig. i.3 foreshadow decades of connections that would be drawn between electronic technologies and the solar system.

These inventors had historical contemporaries whose work was of equal technological significance even if it was less well known. Nikola Tesla, for example, developed alternating current (the AC of AC/DC), an electrical technology that is as crucial to todays everyday infrastructure as any of Edisons inventions. However, Teslas discoveries did not lead to either a public company or a range of industrial and consumer products bearing his name. As a result, the memory of his work was dispersed for a century. The circumstance of Teslas legacy points out that the total universe of electronic experimentation and invention is much broader than what is represented here. As an introduction to electronic technology, this study is confined to the particular trail of evidence found at the intersection of commerce and graphic art.

Next page