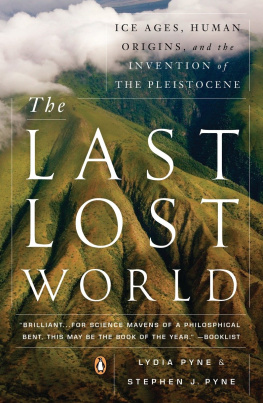

WITH STEPHEN J. PYNE

Copyright 2016 by Lydia V. Pyne

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

INTRODUCTION

FAMOUS FOSSILS, HIDDEN HISTORIES

T he first time I ever met a celebrity was on a June winter morning in Johannesburg.

I was an undergraduate, a student at a paleoanthropology field school in northern South Africa. As part of the summers human paleontology curriculum, we attended a lecture at the University of the Witwatersrand given by the schools eminent scientist, Professor Philip Tobias. For his talk, Professor Tobias had pulled out several well-known fossil specimens from the universitys fossil vault, setting them on flat wooden trays atop red velvet, showing them off like rare gems awaiting our appraisal as we filed into the room to take our seats. As students, we all had seen casts of these fossils before, but these were The Real Thing.

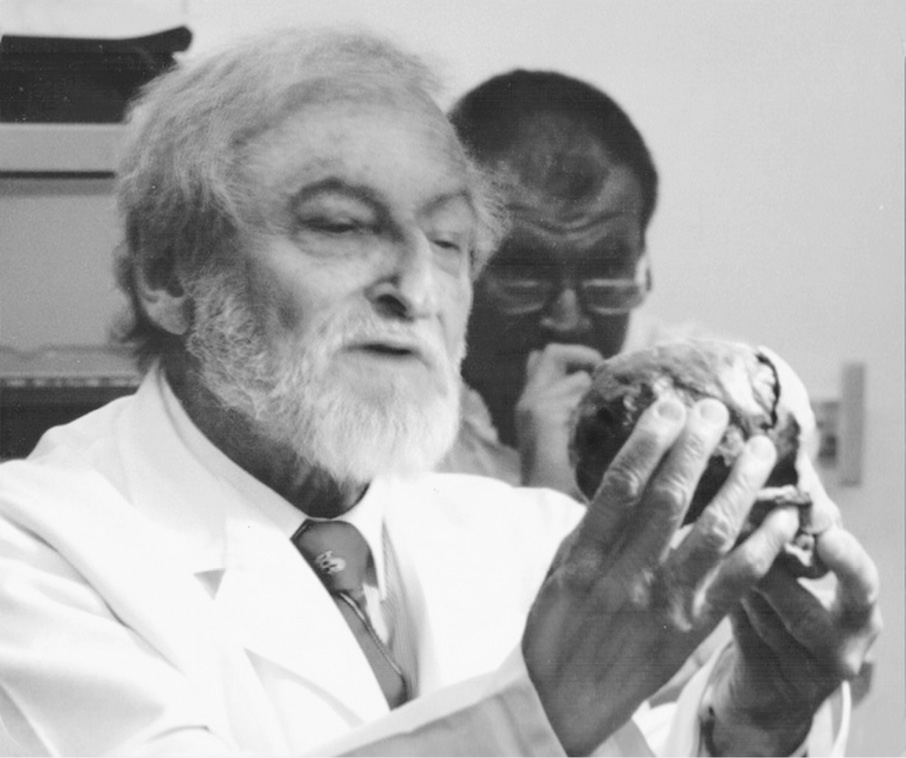

Professor Tobias was a thin, petit man with carefully combed white hair and a meticulously knotted tie. (At a modest five foot four, I felt as if I towered over him.) He arrived for the lecture in a starched white laboratory coat clutching a small wooden box that he put at one end of the lab bench. He began his lecture by describing several of South Africas well-known fossil hominins, or human ancestorspicking up one of the hominin specimens in front of him, turning it over in his hands, pointing out an anatomical feature on the bone, and then carefully putting each fossil back on its tray. The man exuded gravitas and scientific solemnity. The fossils we were looking at represented decades of research and epitomized the crucial role that South Africa plays in understanding human evolution. As the stories about the different fossils seamlessly flowed together, it was obvious that Professor Tobias had given this lecture many times before, but we had never heard it. We were entranced.

But the specimen everyone was particularly keen to see was the Taung Childa fossil whose history has loomed rather larger than life in the science of paleoanthropology. Ever since its discovery in 1924, the story of Taung Child has been chock-full of heroes, villains, theories, petty feuds, and the search for scientific truth. Historical tradition champions the perseverance of the fossils discoverer, Dr. Raymond Dart, in his belief that the fossil was, in fact, a human ancestor and not some aberrant type of fossil apean argument that ran against the grain of the scientific establishment in the early twentieth century. When Darts beliefs were eventually accepted by the scientific community, the story of his dogged belief in his fossil practically became catechism in paleoanthropology that good science will be ultimately vindicated in the face of skepticism.

Back at the fossil demo, Professor Tobias eventually worked his way down to the old wooden box at the end of the table and, with a twinkle in his eye, pulled it closer. Drawing out the anticipation, he finally opened the box with theatrical flair. Reverently, he pulled out a tiny cranium and jaw. The pieces were small, gracile, and easily fit into Tobiass weathered hands; he told us that the wooden box was the same one that Raymond Dart himself had used to store the fossil at the University of the Witwatersrand for decades. After recounting the story of how Dart, whod been Tobiass own academic adviser, found the fossil in a box of breccia from the Buxton Limeworks mine, Tobias put the fossil pieces together so that the lower jaw rested under the Taung Childs tiny face.

The fossil stared out at us, sizing up our group. Professor Tobias moved the little mandible up and down, clicking the fossils tiny front teeth together, and launched into a well-rehearsed comedy act of sorts that had the Taung Child telling a few jokes, commenting on the weather, and offering some insights about the early days of paleoanthropology with his good pal Raymond Dart. This ventriloquy was met with stunned, shocked silence.

The veneration that had surrounded the fossil only moments before when Tobias described its historical significance now seemed oddly out of place. To us earnest undergraduates, it was like vaudeville. How could someone as respected as Professor Tobias show off something as famous as the Taung fossil that way?!? This wasnt the way we were supposed to experience it! The fossil should be in a vault. Or a museum display. Behind glass. Anywhere but auditioning as the straight guy for a Laurel and Hardy act.

Professor Philip Tobias holding the Taung Child. Fossil lecture, University of the Witwatersrand. (L. Pyne)

Over the last century, the search for human ancestors has spanned four continents and resulted in the discovery of hundreds of fossils. While most of these hominin finds live quietly in museum collections for experts to study, there are a few fossil ancestors, like the Taung Child, and others, like Lucy, that have become world-renowned personae, celebrities in their own right. These fossils live lives apart from their museum shelf and catalog numberbecause they are ambassadors of science that speak to nonexpert audiences, they have been given enough cultural cachet to transcend their status as scientific discoveries. Although the methods of scientific inquiry have changed significantly in the last hundred or so years of paleoanthropological researchto say nothing about the fluctuations in research questions and scientific paradigmsthese celebrity fossils still remain part of a cultural gestalt. The fame and importance of these fossil ancestors mean that they are more than just the sum of their science; they play an important role in how audiences interact with scientific discoveries.

But what makes one discovery a celebrity and not another? Why does one fossil hominin come to have a nickname, museum exhibits, or even a Twitter handle while others simply sit in a museum drawer? And why might the answers to those questions depend heavily on the fossils own cultural narrative? Skulls or remains can tell only part of a story. Bones are mute, anthropologist Kopano Ratele suggests. Stories must be told about them. They must be talked about, lectured on, explained, worshipped, searched for, retrieved, commemorated, archived, drawn, photographed and represented to restore their meaning. Knowledge must be built around them.

In order to understand a fossils celebrity, its important to understand what the fossil is, where it comes from, and what kind of context it lives in. In other words, we need to situate the fossil within its own cultural history, giving it a biography built out of museums, archives, media, peoplethe countless interactions throughout the fossils life after its discovery.