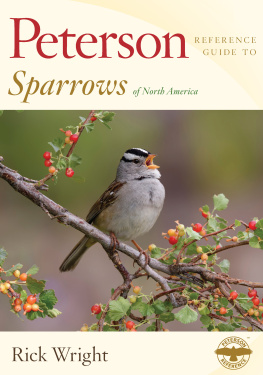

Copyright 2019 by Rick Wright

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-547-97316-6

Cover photograph Alan Murphy / BIA / Minden Pictures / Getty

Author photograph Alison Beringer

eISBN 978-0-547-97317-3

v1.0219

ROGER TORY PETERSON INSTITUTE OF NATURAL HISTORY

Continuing the work of Roger Tory Peterson through Art, Education, and Conservation

In 1984, the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History (RTPI) was founded in Petersons hometown of Jamestown, New York, as an educational institution charged by Peterson with preserving his lifetime body of work and making it available to the world for educational purposes.

RTPI is the only official institutional steward of Roger Tory Petersons body of work and his enduring legacy. It is our mission to foster understanding, appreciation, and protection of the natural world. By providing people with opportunities to engage in nature-focused art, education, and conservation projects, we promote the study of natural history and its connections to human health and economic prosperity.

ArtUsing Art to Inspire Appreciation of Nature

The RTPI Archives contains the largest collection of Petersons art in the worldiconic images that continue to inspire an awareness of and appreciation for nature.

EducationExplaining the Importance of Studying Natural History

We need to study, firsthand, the workings of the natural world and its importance to human life. Local surroundings can provide an engaging context for the study of natural history and its relationship to other disciplines such as math, science, and language. Environmental literacy is everybodys responsibilitynot just experts and special interests.

ConservationSustaining and Restoring the Natural World

RTPI works to inspire people to choose action over inaction, and engages in meaningful conservation research and actions that transcend political and other boundaries. Our goal is to increase awareness and understanding of the natural connections between species, habitats, and peopleconnections that are critical to effective conservation.

For more information, and to support RTPI, please visit rtpi.org.

To Alison

Introduction

Most bird books treat their subject as one entirely separate from the cultural world that humans inhabit, focusing exclusively on what for the past 2,500 years we have called natural history: identification, behavior, and ecological and evolutionary relationships. But birds have a human history, too, beginning with their significance to Native cultures and continuing through their discovery by European and American science, their taxonomic fortunes and misfortunes, and their prospects for survival in a world with ever less space for wild creatures.

That human history is made up not just of facts and measurements but of stories. Some of those stories are amusing, some sobering, but all should remind the reader of one important truth: everything we think we know, someone else had to learn. A fuller awareness of the slow evolution of ornithological knowledge over the centuries can inspire modern birders both to greater ambition and to greater patience with their own development. If scientific ornithology is still debating the status, indeed the very existence, of, for example, the Cassiar Junco a century after its discovery, we field observers can be more comfortable in our own uncertainties.

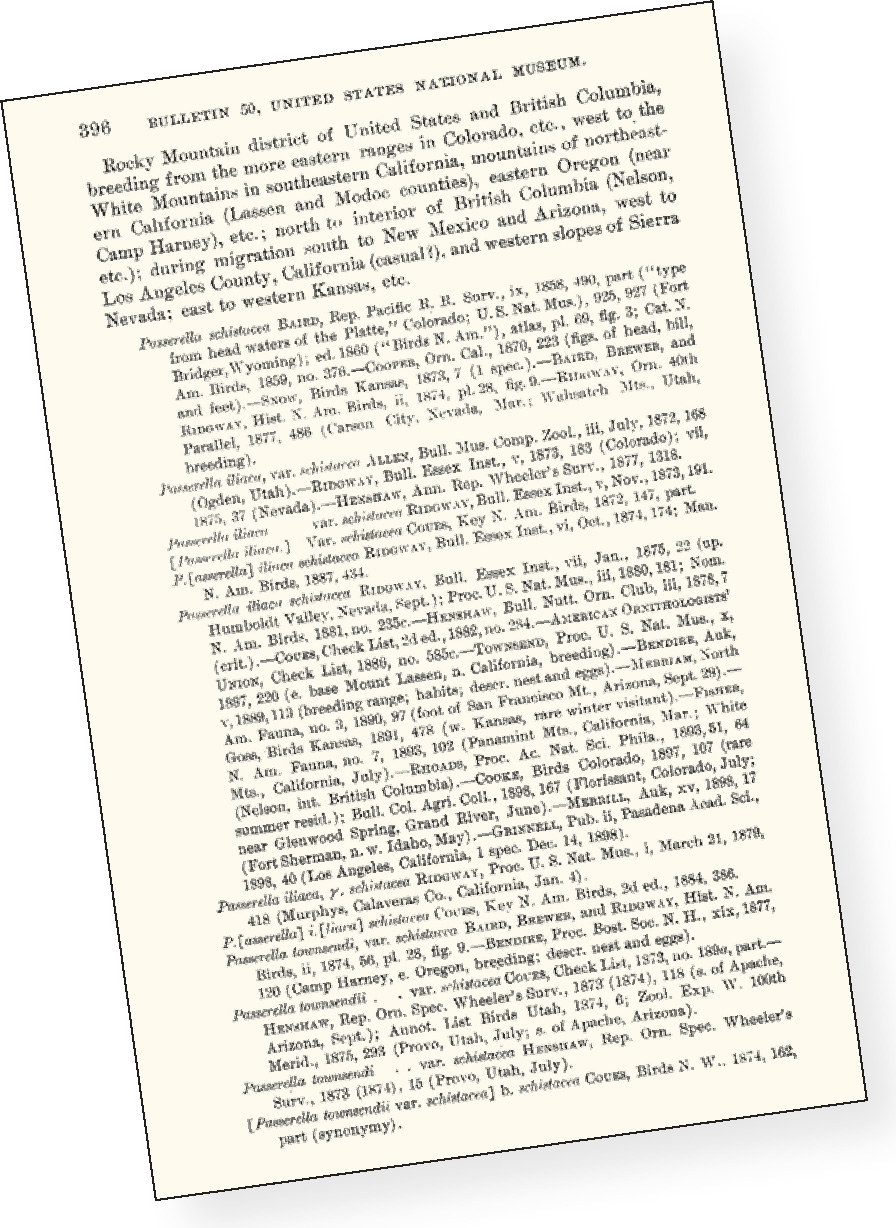

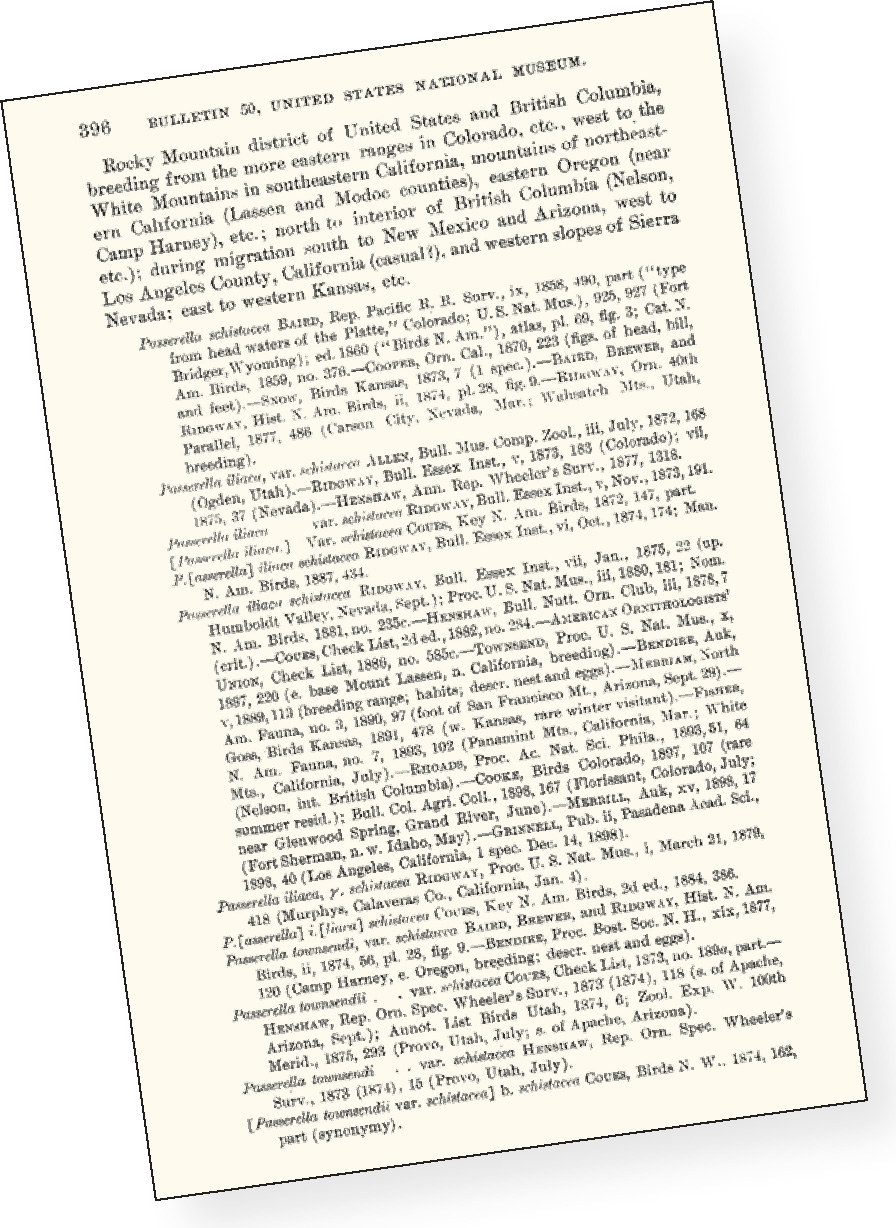

Much of a birds human history is revealed in its changing taxonomythe names (scientific and vernacular) assigned a species over time. Tracing the nomenclatural career of a bird over the decades and centuries is one of the best routes to track the ways that ornithological and popular observers alike have tried to come to terms with a new, odd, or particularly interesting bird. Read in this way, even the driest of synonymies becomes a trove of bird and birding lore that can only deepen our appreciation of our forebears efforts to untangle some of the knottiest problems in American natural history.

It is impossible, especially in a volume as reluctantly slender as this one, to tell all of the stories associated with all of the names assigned to all of the American sparrows over all time. Instead, for each species, subspecies, or flavor of sparrow, we have selected one or two anecdotes that illuminate the confrontation between humans and birds over the years. Virtually every sparrow taxons human history could fill a book of its own, and it is hoped that readers will find their interest piqued sufficiently to dig deeper into the great store of birding and ornithological knowledge of these only apparently bland little birds.

This apparent Cassiar Junco gives every indication of confidence in its own existence.

Cathy Sheeter

A NOTE ON NOTES

The end notes, beginning on , provide bibliographical citations to the sources of quotations, paraphrases, and other explicit references, with the exception of eBird data and identification information drawing on Peter Pyles Identification Guide to North American Birds, Vol. 1 (Salinas: 1998), both of which are cited parenthetically in the text.

WHAT IS A SPARROW?

Some English names for birds are unequivocal. All birders (and many non-birders) have essentially the same mental image of a pelican, a duck, or a flamingo, and a guide dedicated to waxwings or kingfishers would need nothing more than a sketch and a single sentence to satisfactorily identify its subject. In all those and many other cases, a clearly defined term is precisely applied to a neatly delimited avian group.

Other bird names are more difficult to pin down. Notoriously, the same English word can denote birds that are entirely differentand often not even closely related. Sparrow, unfortunately, is a particularly complicated example of the ways in which the conventional scientific use of a term can diverge significantly and confusingly from its natural usage in everyday language.

If any science out-dismals economics, it is bibliography. But following up on the fine print can lead us deep into the human history of natural history.