Rosen - Music and Sentiment

Here you can read online Rosen - Music and Sentiment full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New Haven Conn, year: 2010, publisher: Yale University Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Music and Sentiment

- Author:

- Publisher:Yale University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- City:New Haven Conn

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Music and Sentiment: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Music and Sentiment" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rosen: author's other books

Who wrote Music and Sentiment? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Music and Sentiment — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Music and Sentiment" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MUSIC AND SENTIMENT

CHARLES ROSEN

MUSIC AND

SENTIMENT

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN AND LONDON

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund

Copyright 2010 by Charles Rosen

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S, Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications please contact:

U.S. Office: sales.press@yale.edu yalebooks.com

Europe Office: sales@yaleup.co.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk

Set in Arno Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rosen, Charles, 1927

Music and sentiment / Charles Rosen.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-300-12640-2

1. MusicPhilosophy and aesthetics. 2. MusicHistory and criticism. I. Title.

ML3845.R69 2010

781'.11dc22

2010016214

ISBN 978-0-300-12640-2

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Kristina Muxfeldt

T HIS book was written from the conviction that understanding music does not come from memorizing an esoteric code. Many aspects of music, of course, benefit from a long study, but grasping its emotional or dramatic meaning is either immediate or requires only becoming familiar with it. Understanding music in the most basic sense simply means enjoying it when you hear it. It is true that with music that is unfamiliar and seems alien at first hearing, this requires a few repeated experiences of it and, indeed, a certain amount of good will to risk new sensations. It is, nevertheless, rare that specialized knowledge is required for the spontaneous enjoyment that is the reason for the existence of music. However, specialized study can bring rewards by allowing us to comprehend why we take pleasure in hearing what we appreciate best, and can enlighten us on the way music acts upon us to provide delight.

These chapters began as the William T. Patten Lectures at the University of Indiana at Bloomington in the year 2002. I enjoyed my brief stay there very much, as it is one of the most impressive centers of the study of music, with an astonishing range of activity.

I have been less concerned with identifying the sentiments represented by the music than with the radical changes in the methods of representation throughout two centuries, as these changes reveal important aspects of the history of style. In addition, seeing how the sentiment is represented is more important to our comprehension of the music than putting a name tag on its meaning. In fact, the significance of the musics sense is best clarified when we know the different ways that it could be revealed.

I am deeply indebted to Robert Marshall, emeritus professor of Brandeis University, for sharing his wisdom on the subject. I owe special thanks to Professor Kristina Muxfeldt of the University of Indiana at Bloomington for all her generous aid and friendship. I would never have written any book after my university thesis without the stimulus and help of Professor Henri Zerner of Harvard University. I owe a great debt to Malcolm Gerratt at Yale University Press, and am very grateful to the press for all its encouragement and patience.

I N Shakespeares The Merchant of Venice, act V, scene 1, we find this exchange between the two young lovers:

JESSICA I am never merry when I hear sweet music

LORENZO The reason is, your spirits are attentive

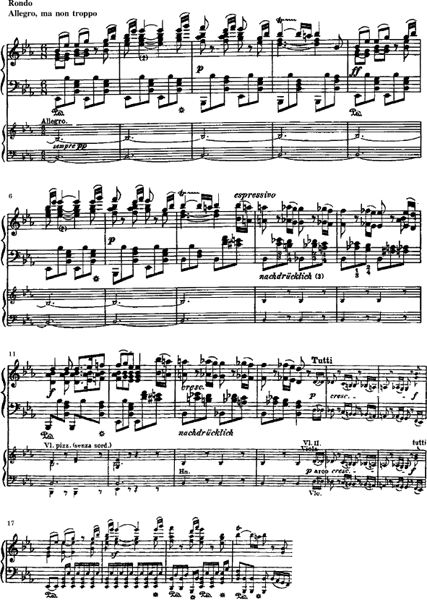

The opening of the finale of Beethovens Emperor Concerto provides a splendid example of the kind of theme that is the inspiration for this book. A completely unified theme that hangs together beautifully, it nevertheless portrays vividly a series of contrasting sentiments in a succession that amounts to a small narrative:

This is not always perfectly realized in performance, due to an error in the tempo marking that has taken almost two centuries to correct. The correct tempo is not simply Allegro, as most editions have it, but Allegro, ma non troppo. The slightly slower tempo is necessary to make clear the radical contrast between the rhythmically complex, heavily pedalled fortissimo fanfare of the first two bars and the simple German dance rhythm (Teutscher or Allemande) of bars 3 and 4, now soft and certainly intended to be performed with a lilting grazioso. After these four bars are repeated, a third sentiment is introduced with the indication of espressivo still within the soft dynamics of bars 3 and 4 in Beethoven, as in most of his contemporaries, espressivo generally implied a slight slackening or freedom of tempo. This espressivo lasts for two bars and leads directly into a new and different affective atmosphere, a more boisterous version of the simple German dance rhythm. The espressivo quickly returns: and since it is now marked crescendo, I assume that an initial return to the dynamic of piano is intended at first, but the new indication of crescendo reduces the contrast with the previous bars made by the first appearance of the espressivo phrase. The orchestra at last takes over the theme, and reduces the contrast between bars 1 to 2 and 3 to 4, playing the whole theme forte with much more agitated inner voices. The graceful lilt of bars 3 and 4 is now assimilated to the decisive energy of bars 1 and 2. All the expressive details of the pianos fourteen bars are reduced to a uniform forte. This overriding of the affective contrasts and oppositions within the theme is an essential trait of the style of the period.

It is intriguing that such a theme that combines different sentiments with strong contrast does not exist in music before the last decades of the eighteenth century. And it largely ceases to exist after the death of Beethoven. It is then replaced by a different and entirely new kind of complexity in the illustration of sentiment, while a still more novel method of representation appears at the end of the nineteenth century. The following pages examine how the change in representing sentiment in music was developed, and what it could mean for the conception of music its style and its function.

In order to make the subject manageable, I shall treat mainly the initial presentation of a theme, as any extensive account of the way the meanings of motifs change in the course of a work would carry us too far afield, although on a few occasions I shall have to mention these developments briefly.

D EALING with the representation of sentiment in music, I shall not often attempt to put a name to the sentiment, so readers who expect to find out what they are supposed to feel when they listen to a given piece of music will be inevitably disappointed. Happily, however, it is mostly quite obvious. That is: some music is sad and some is jolly. Sometimes it is ferocious or funereal and sometimes tender and there is little difficulty in deciding what sentiment is being represented (but somewhat later we shall discuss the rare occasion and the odd reason for a mistake to be made in our response). The frivolity of naming the sentiments arises largely from the fact as Mendelssohn once famously observed that music is much more precise in these matters than language. The communication of information is one of the most important of the many different functions of language, but not of music (you cannot, for example, by purely musical means, ask your listeners to meet you tomorrow at Grand Central Station at 4 oclock). However, language must seek out poetic methods even to approach at a distance the subtlety and emotional resonance of music.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Music and Sentiment»

Look at similar books to Music and Sentiment. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Music and Sentiment and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.