WHAT MAKES CIVILIZATION?

WHAT MAKES CIVILIZATION?

THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST AND THE FUTURE OF THE WEST

DAVID WENCROW

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

David Wengrow 2010

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd., St Ives Plc

ISBN 9780192805805

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

for Abigail, everything is possible

CONTENTS

LIST OF MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

Maps (Created and Drawn by Mary Shepperson)

Illustrations

1. Gold casing of a cult statue with lapis lazuli inlays around the eyes, from Tell el-Farkha in northern Egypt, c.3200 BC (Late predynastic period).

2. Marble face of a composite figure, with shell and lapis lazuli inlays, from Mari, Syria, c.2500 BC.

3. Monumental stone tower constructed around 9000 Bc (Pre-pottery Neolithic A period) at the site of Jericho (Palestine), preserved to a height of around 9 metres.

4. Human skull with features modelled in plaster, and eyes inlaid with Red Sea shells, c.7500 BC (Pre-pottery Neolithic B period).

5. Comb with bird ornament, c.3500 BC, from a grave at Ballas in Upper Egypt (Predynastic period).

6. Ceramic serving vessels of the sixth millennium BC (Halaf period), from northern Iraq.

7. Copper sceptres, mace-heads, and other ceremonial objects cast in the lost-wax technique, from a hoard discovered at Nahal Mishmar in the Judean Desert (Israel), dating to the late fifth or early fourth millennium BC.

8. I mages impressed onto the clay sealings of storage vessels, and illustration of sealing mechanism (above: Ubaid-period stamp impressions, fifth millennium BC; below: Uruk-period cylinder impression, late fourth millennium BC).

9. Tell Brak (ancient Nagar), in Syria, where urban life dates back to at least 4000 BC. Today its remains still stand over 40 metres above the Upper Khabur plain.

10. Ceramic pouring vessel from the time of the Uruk Expansion, c.3200 BC, from Habuba Kabira, Syria.

11. Cosmetic palette inscribed with the name of King Narmer, one of Egypts earliest rulers, c.3100 BC, obverse face.

12. Early cuneiform account (damaged) of bread and beer from the site of Jemdet Nasr, southern Iraq, c.3000 BC.

13. Stone plaque of Ur-Nanshe, ruler of Lagash, c.2500 BC.

14. Monumental mud-brick architecture at the end of the fourth millennium BC: the White Temple at Uruk, southern Iraq (above), and an elite tomb at Saqqara, northern Egypt (below).

15. Relief carving of a seated statue in transit, receiving an offering of incense, from the tomb of Rashepses at Saqqara, Old Kingdom, c.2400 BC.

16. Plan of the workers settlement near the pyramids of Giza, Old Kingdom, with adjoining towns and fortifications.

17. Syrian bears and vessels arriving in Egypt. Painted limestone relief from the mortuary temple of Sahure at Abusir, c.2450 BC.

18. Tympanum above the entrance to the Oriental Institute in Chicago.

19. Bronze medallion commemorating the publication of Description de lgypte, 1826.

20. General Napoleon Bonaparte, before the pyramids, contemplates the mummy of a king (Egyptian Expedition 1798).

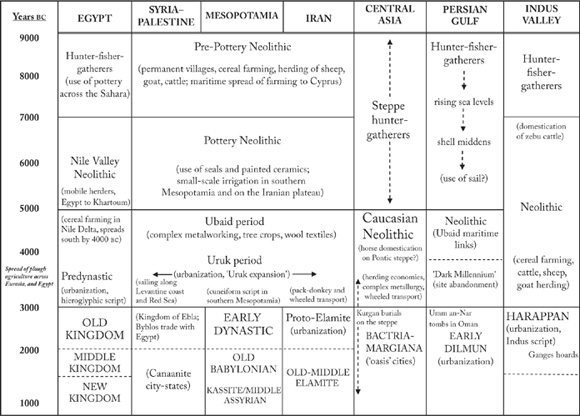

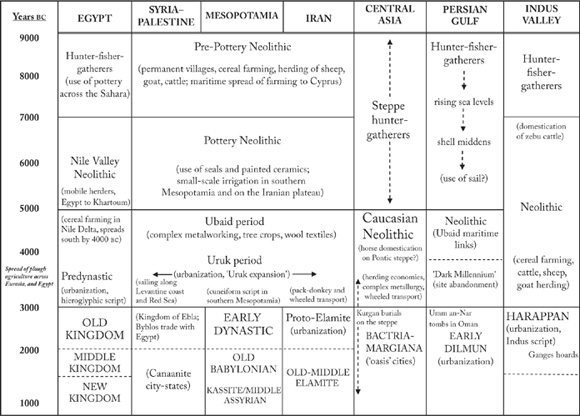

Chronology Chart

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

W hen the Iraq Museum in Baghdad was looted in 2003, eight decades after its foundation by the British diplomat and archaeologist Gertrude Bell, our newspapers proclaimed the death of history. It is easy to see why. After the end of the last Ice Age, around 12,000 years ago, the Middle East witnessed a series of startling transformations that were unprecedented in human history, and have shaped its course down to the present day. By 8000 BC the worlds first substantial and permanent settlements had been established there, accompanied by the earliest domestication of cereal crops and herd animals. Over successive millennia farming spread to neighbouring regions, including the Mediterranean and northern Europe. But in the Middle East itself, further developments unfolded that would remain alien to most of Europe for many thousands of years. By 4000 BC cities of great size and complexity had appeared along the rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates, in what is today Iraq. The invention of the earliest known system of writing followed in that region (referred to by historians as ancient Mesopotamia) around 3300 BC, echoed to the west along the Egyptian Nile, where a distinct group of scripts emerged at much the same time.

This book provides a new account of these remarkable changes in human society and technology, and many others that accompanied them. But its main focus is upon the succeeding period, from around 3000 to 2300 BC, which witnessed the parallel rise of powerful kingdoms, centred upon what are now the countries of Egypt and Iraq, and taking markedly different forms in each. These were the first really large-scale political entities to emerge in human history, the superpowers of their day. It is their appearance that archaeologists and ancient historians, writing in a more innocent age, have referred to as the birth of civilization in the ancient Near East. And even if the grandeur of that particular phrase no longer appeals, our attachment to the ancient Near East as the birthplace of civilization, where the foundations of our own societies were laid, remains as strong today as it has ever been.

Alongside such positive appraisals, however, there exists the memory of another kind of ancient Near East; an alien and sometimes bizarre world where we explore the discontents of modern civilization; where the allure of sacred kingship can still be felt, and the fate of humans is directed by the will of distant and unfathomable gods. Most people today are more likely to encounter ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia through the lens of Hollywood, or works of fiction such as William Blattys

Next page