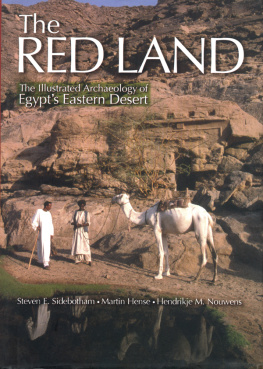

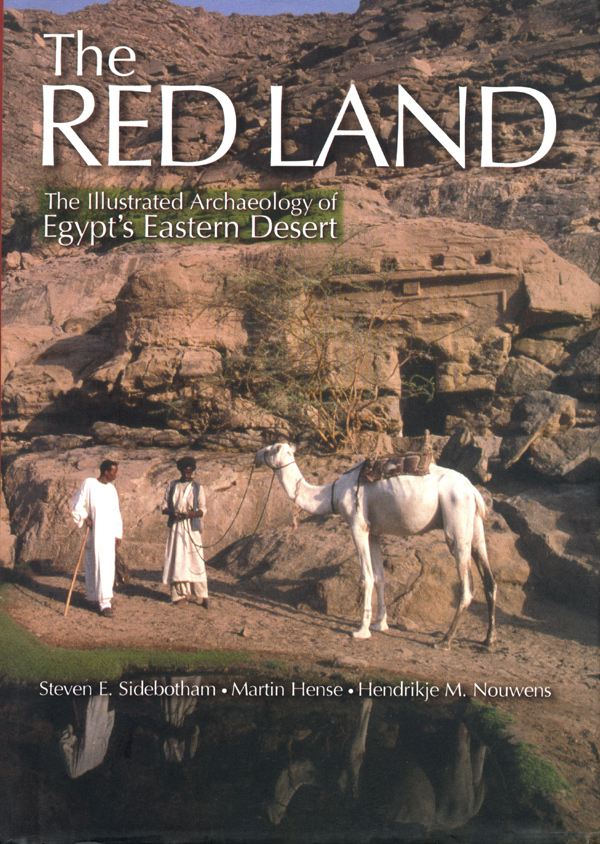

The

RED LAND

The

RED LAND

The Illustrated Archaeology of

Egypt's Eastern Desert

Steven E. Sidebotham

Martin Hense

Hendrikje M. Nouwens

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

Copyright 2008 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Dar el Kutub No. 3130/07

e-ISBN 978 161 797 226 3

Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sidebotham, Steven

The Red Land: The Illustrated Archaeology of Egypt's Eastern Desert / Steven Sidebotham.Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2007

p. cm.

ISBN 977 416 094 0

1. DesertsEgypt 2. Eastern DesertEgypt I. Hense, Martin (jt. auth.)

II. Nouwens, Hendrikje M. (jt. author.) III. Title

916.35

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 12 11 10 09 08

Designed by Sally Boylan / AUC Press Design Center

Printed in Egypt

Contents

Figures

Plates

W orking in the Eastern Desert of Egypt over the years has had its share of challenges, but its haunting beauty, the incredible state of preservation of many of its ancient archaeological remains, and the friendliness of its Bedouin inhabitants have completely captivated us. This book is a snapshot of our experiences in the Eastern Desert and cannot begin to convey a complete impression of this arid wilderness, nor can it adequately express our dedication to the protection and preservation of its beautiful natural and historical treasures and its rich Bedouin heritage from the ravages of the modern world. We hope this book will inspire in our readers an appreciation for this remote and often overlooked area of the world.

There are numerous individuals and institutions that have helped us in our fieldwork over the decades. They are too many to mention here, but their names can be found listed in our many publications. Of most immediate help were those who actually made this book possible. These include Ms. Mary Caulfield on whose computer much of this text was composed and who spent countless hours scanning hundreds of slides as digital images. Ms. Angie Hoseth, Ms. Tracy Jentzsch of the History Media Center, History Department, University of Delaware, USA, and Ruud Koningen from the Netherlands also cheerfully and tirelessly scanned hundreds of slides as digital images. Prof. William Leadbetter of Edith Cowen University, Perth, Australia generously provided his personal computer on which much of this text was edited while Sidebotham was a visiting scholar there in December 2006. Prof. James A. Harrell of the University of Toledo read and commented on the geology sections of the book.

There is always the vexing question of the transliteration of Arabic words and proper names into the Latin alphabet. We have attempted to use the most commonly accepted and most recognizable spellings. With the el/al prefixes, we have opted to use at. For many proper Eastern Desert place names we have presented here our transcriptions of Maaza and Ababda pronunciations, which do not always coincide with spellings that appear on modern maps. All ruling/reigning dates are based on J Baines and J Mlek, Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt (NewYork: Checkmark Books, 2000).

We would like to dedicate this book to all our Maaza and Ababda Bedouin friends who, over the years, have taught us so much about themselves and their lives in the Eastern Desert.

The earliest traces of human occupation in the Nile Valley and the surrounding deserts survive along the desert hills and terraces in Upper Egypt and Nubia. They consist of large, roughly shaped flint tools, such as handaxes and scrapers, dated about 250,000 BC. These primitive tools, similar to those found in Europe in the Lower Paleolithic period, were made by nomads and hunters ranging over all of North Africa.

Toward Late Paleolithic times, in approximately 25,000 BC, the climate of the region underwent a drastic change and grass steppes began to turn into desert. As a result, early man had to withdraw from his old hunting grounds toward sources of water; in this period traces of more settled occupation have been found in the Nile Valley.

During the Mesolithic period (about 10,0005000 BC) the population of Egypt comprised different groups of semi-nomadic fishermen and hunters living in comparative isolation one from another. The use of flint during this time was much developed and smaller, finer tools for specialized purposes have been discovered, including arrowheads, while blade industries became common. It is possible that the last survivors of these fishing and hunting bands were those who executed the rock-carvings in the cliffs overlooking the Nile Valley and in the wadis leading to the Red Sea in southern Egypt and Nubia.

The first positive evidence for the domestication of cereal crops in Egypt comes with the remains of the first settlements in the Neolithic period (about 50004000 BC). The inhabitants of sites on the western edge of the Nile Delta, in the Fayyum region (a large fertile depression in the Libyan Desert southwest of Cairo), and in Middle Egypt clearly lived a settled agricultural life. They cultivated cereals and flax and raised domesticated animals. Climatic conditions improved in the sixth millennium BC and a moist interval probably facilitated agriculture and stock breeding. Furthermore, fishing, weaving, basketry, and pottery-making played an important role in the economy of these early farmers.

The late Neolithic period in Egypt is generally described as Predynastic and began in the fourth millennium BC. This was a time of great innovation and development, which ended with the unification of Egypt at the beginning of the First Dynasty (approximately 3000 BC).

The early Predynastic cultures were not homogenous; rather there were two main regions, Upper and Lower Egypt, and these developed along different lines. Little was known about the earliest inhabitants of Egypt until the end of the nineteenth century when discoveries of Predynastic cemeteries were made in Upper Egypt, and excavations in Lower Egypt led to the recovery of settlement remains.

Most of the Predynastic cultures in Egypt are named after the village place names where the culture was first identified. The earliest known phase of the Upper Egyptian Predynastic period, which was not discovered until the 1920s, is known as the Badarian period (5500about 4000 BC). The al-Badari region, between Matmar and Qaw, includes several Predynastic cemeteries which yielded numerous finds, including the earliest copper objects found in Egypt, as well as terra-cotta and ivory anthropomorphic figures, palettes of slate for grinding eye-paint, stone vases, and flint tools. The pottery of the Badarian period is particularly fine and was to become very common in later times: the distinctive black-topped red ware, with its carefully polished surface.

Next page