Contents

Landmarks

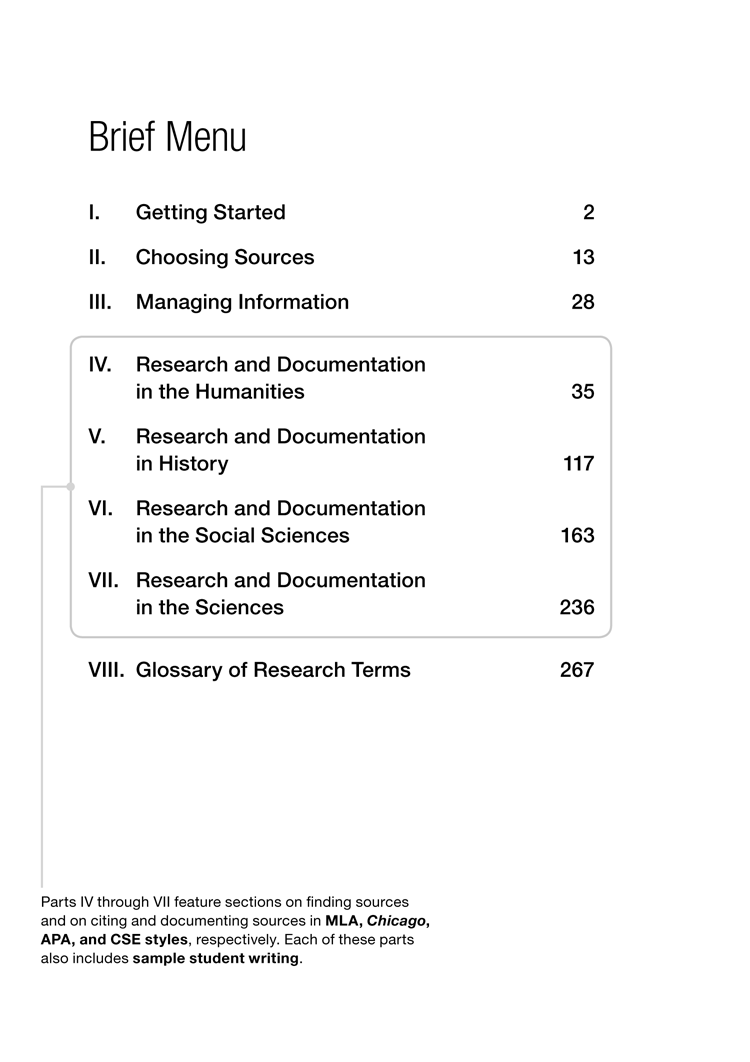

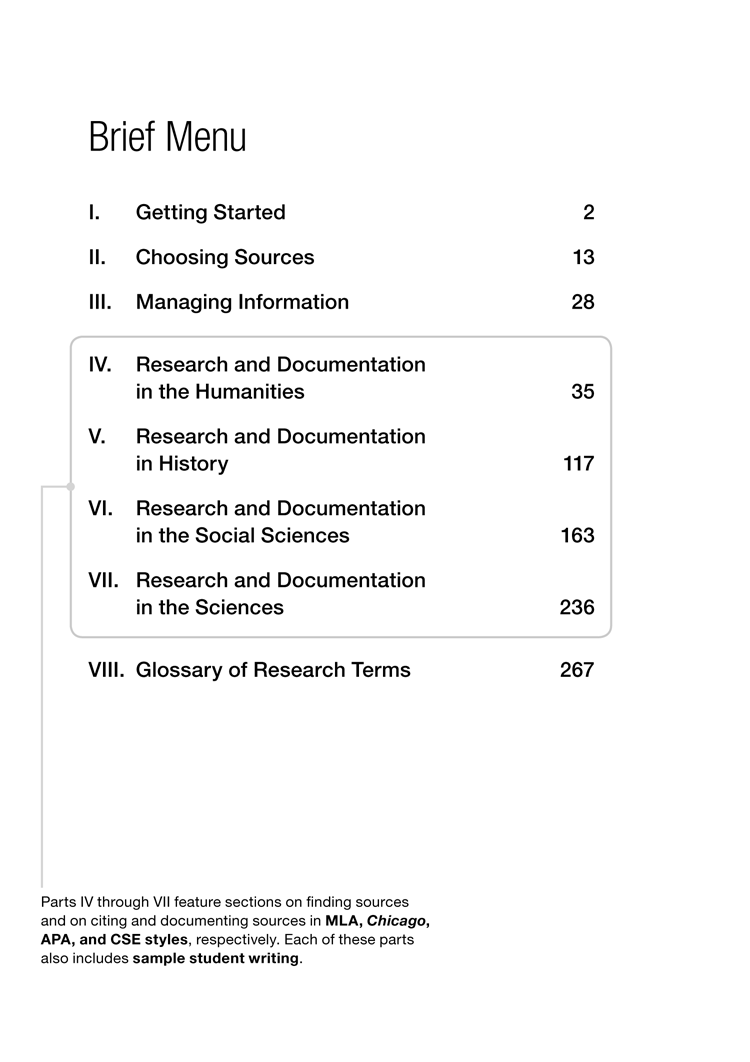

Brief Menu

1.Getting Started2

II.Choosing Sources13

III.Managing Information28

IV.Research and Documentation tn the Humanities35

V.Research and Documentation in History117

VI.Research and Documentation in the Social Sciences163

VII.

Research and Documentation in the Sciences236

VIII.Glossary of Research Terms267

Parts IV through VII feature sections on finding sources and on citing and documenting sources in MLA, Chicago, APA, and CSE styles, respectively. Each of these parts also includes sample student writing.

Research and Documentation in the Digital Age

Research and Documentation in the Digital Age

Seventh Edition

Diana Hacker

Barbara Fister

Gustavus Adolphus College

For Bedford/St. Martins

Vice President, Editorial, Macmillan Learning Humanities: Edwin Hill

Senior Program Director for English: Leasa Burton

Senior Program Manager: Stacey Purviance

Director of Content Development: Jane Knetzger

Executive Editor: Michelle M. Clark

Development Editor: Cara Kaufman

Marketing Manager: Vivian Garcia

Senior Content Project Manager: Christina Horn

Workflow Project Supervisor: Joe Ford

Production Supervisor: Robin Besofsky

Media Project Manager: Allison Hart

Editorial Services: Lumina Datamatics, Inc.

Composition: Lumina Datamatics, Inc.

Permissions Editor: Angela Boehler

Photo Researcher: Kerri Wilson

Cover Design: William Boardman

Copyright 2019, 2015, 2010, 2009 by Bedford/St. Martins.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except as may be expressly permitted by the applicable copyright statutes or in writing by the Publisher.

3 2 1 0 9 8

f e d c b a

For information, write: Bedford/St. Martins, 75 Arlington Street, Boston, MA 02116

ISBN 978-1-319-20206-4(EPUB)

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and copyrights appear on the same page as the text and art selections they cover; these acknowledgments and copyrights constitute an extension of the copyright page.

Reviewers

For their candid feedback, smart suggestions, and welcome expertise, we thank the following reviewers:

Nancy Sosna Bohm, Lake Forest College

Anne-Marie Deitering, Oregon State University

Diana Matthews, Santa Fe College

Ruth Mirtz, University of Mississippi

Maura Smale, New York City College of Technology

Barbara Wurtzel, Springfield Technical Community College

Introduction

This compact reference from Bedford/St. Martins gives you quick access to useful tips and models youll need as you make your way through the research process.

Parts I through III offer advice about planning and managing research projects that use information from published print and online sources. Parts IV through VII explore research tools and approaches in thirty-one academic disciplines, such as nursing, criminal justice, and anthropology, followed by documentation rules and examples for writing in the humanities, history, social sciences, and sciences. Finally, Part VIII provides a glossary of research terms used across the disciplines.

Research and Documentation in the Digital Age, Seventh Edition, is also available as an e-book. Visit macmillanlearning.com/resdoc7e/catalog for more information.

Part I . Getting Started

Research assignments in college are an invitation to join a conversation about ideas by exploring a topic in depth, weighing relevant evidence, and drawing your own conclusions. To do this, you need to explore widely to discover what issues are under debate, settle on a question to investigate, learn what others have had to say about that question, and write your own response, drawing on persuasive and well-chosen evidence. How you tackle your research will vary depending on the research question you are posing and the subject area in which conversations about the issue are being held. Historians will pose different questions about immigration than political scientists; scientists studying autism may be interested in its genetics, while education researchers may be more interested in effective teaching strategies for children with autism. Finding your way into those conversations is key to developing a focused research question and sharing your own thoughts effectively.

In general, a good research topic is one that is relevant to your course and excites your curiosity. Narrowing and defining that topic takes time. Youll need to collect background facts about your potential topics so that you have a foundation for your research. You might, for example, browse articles online and consult your textbook or other class readings. Librarians can also guide you to specialized reference works such as the Encyclopedia of Applied Ethics or CQ Researcher that cover a wide variety of controversial topics in short, thoroughly researched, even-handed articles.

With that factual foundation in place, youll want to see how people are debating, analyzing, and interpreting the issue you are interested in. For this purpose, you might turn to the web or search a library database to see what scholars, journalists, and members of the general public have said about it. It may also be useful to browse the website of a publication, organization, or government agency that covers breaking news and important issues related to your topic to get a sense of what debates exist and which ones strike you as worth exploring.

Seeing the big picture

When you get started on a research project, you need to understand the assignment, choose what direction to head in, and quickly get the big picture for the topic you choose. You then have to fit all of these tasks into a schedule that may already be a bit crowded. When you receive your assignment, set a realistic schedule of deadlines. Think about how much time you might need for each step on the way to your final draft.

At first your research will be a broad scan of the topic to see what aspect of it might be most interesting. This stage of research is like walking into a room full of people talking about a topic youre exploring. Its a babble of voices, and at first it is a bit overwhelming. As you move through the room, you overhear something interesting and pause to listen. After overhearing several bits of conversation, one discussion really grabs your attention, so you join the group, listen to various perspectives, and weigh in with your own thoughts. Throughout the process, you will be looking for information, but your search will grow more focused and purposeful over time.

As you begin the process of discovering what conversations are going on around a particular topic, a reference librarian may be able to recommend a library database that focuses on articles relevant to a particular subject such as nursing or psychology, or may help you brainstorm good search terms to use in a database that covers multiple subject areas. Most libraries also have subject guides on their websites that will help you find and explore resources relevant for your course. For some subjects it might be helpful to use the librarys catalog to find current books relevant to your research and then browse the shelves nearby to see what approaches different writers have taken to the topic.