Patients

at Risk

Patients

at Risk

The Rise of the Nurse Practitioner and

Physician Assistant in Healthcare

Niran Al-Agba, m.d.

Rebekah Bernard, m.d.

Patients at Risk:

The Rise of the Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant in Healthcare

Copyright 2020 Niran Al-Agba and Rebekah Bernard. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC) at 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. For organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by the CCC, a separate system of payments has been arranged.

Universal Publishers, Inc.

Irvine Boca Raton

USA 2020

www.Universal-Publishers.com

ISBN: 978-1-62734-316-9 (pbk.)

ISBN: 978-1-62734-317-6 (ebk.)

Typeset by Medlar Publishing Solutions Pvt Ltd, India

Cover design by Ivan Popov

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Al-Agba, Niran, 1974- author. | Bernard, Rebekah, 1974- author.

Title: Patients at risk : the rise of the nurse practitioner and physician assistant in healthcare / Niran Al-Agba, M.D., Rebekah Bernard, M.D.

Description: Irvine : Universal-Publishers, Inc., [2020] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020034646 (print) | LCCN 2020034647 (ebook) | ISBN 9781627343169 (paperback) | ISBN 9781627343176 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Patients--Safety measures. | Medical errors--Prevention. | Physician and patient.

Classification: LCC R729.8 .A43 2020 (print) | LCC R729.8 (ebook) | DDC 610.28/9--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020034646

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020034647

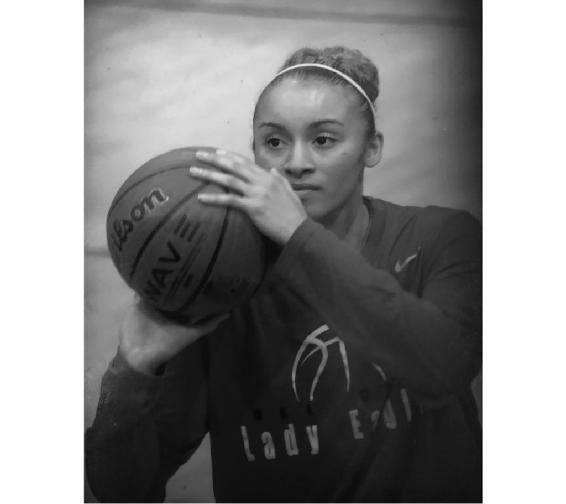

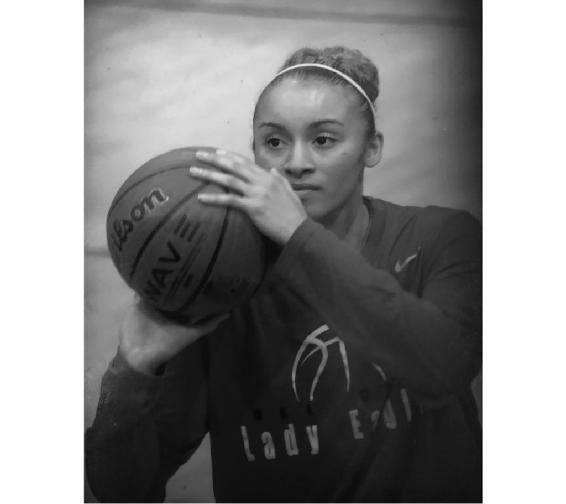

DEDICATION

T his book is dedicated to the memory of Alexus Jamel Ochoa-Dockins and the countless others who have been harmed by a healthcare system corrupted by greed. May the telling of her story give a voice to those who have been silenced and lead to changes in healthcare policy that will ensure that all patients receive equitable, high quality medical care.

(Photo contributed by family)

Table of Contents

Introduction

O n a sunny Tuesday in March 2015, the steps of Capitol Hill were draped in white as nurse practitioners from across the United States descended on the nations capital. Their long white coats flapping, and stethoscopes draped around their necks, the lobbyists marched with determined steps.

The organizer of the event, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, called it a record day. Nurse practitioners had scheduled more than 250 visits with legislators.

The nurse practitioners had a compelling argument. The cost of the 15,000 hours of training required of physicians before being permitted to practice medicine is much higher than the minimum 500 hours required of nurse practitioners. At the same time, lobbyists showed lawmakers studies that appeared to indicate that nurse practitioners were just as safe and effective as physicians, despite this difference in training and experience. So, why pay for the high cost of medical school and residency for physicians when nurses can be trained in less time and for less money?

Lawmakers listened attentively to these arguments. Representatives with large rural constituencies were particularly intrigued by the idea that nurse practitioners could increase access to healthcare in underserved areas. After all, economists were once again predicting a physician shortage, and nurse practitioners promised to fill that void.

By 2019, legislators in 23 states and Washington DC were convinced. Despite opposition from physician and patient advocacy groups, lawmakers in these states granted nurse practitioners the right to provide medical care to patients without physician supervision. Corporations and private equity markets were delighted. Instead of paying top dollar for fully trained physicians, these organizations now had the green light to hire less expensive nurse practitioners. Retail pharmacies across the nation rushed to install nurse practitioners into mini-clinics on every corner. Hospitals began to staff emergency departments and intensive care units with doctors of nursing. University medical centers even began to utilize nurse practitioners to teach medical students and resident physicians. Noting the success of nurse practitioners, other groups began to follow suit, with physician assistants, pharmacists, and psychologists lobbying for expanded practice rights.

With an increased demand for nurse practitioners, private, for-profit training programs rapidly emerged. These programs competed fiercely for student tuition dollars, boasting 100% acceptance rates to potential students,

Experienced nurse practitioners who completed their training at traditional brick-and-mortar nursing institutions complained that these programs were nothing more than diploma mills offering inadequate clinical experience. However, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners did nothing to slow down the production of new graduates. Increasingly, nurse practitioners were starting their first day of work with little to no nursing experienceand corporations were ready to hire them to care for patients independently, no questions asked, due to the lower payroll costs compared to trained physicians.

Unfortunately, most Americans have remained dangerously unaware of this revolution in healthcare. Being treated by a non-physician is not on the radar of the average patient, most of whom assume that anyone in a white coat is a physician. If patients do wonder about being treated by a non-physician, they are reassured that their nurse practitioner or physician assistant is just as good as a doctor, an idea reinforced by multi-million-dollar direct-to-patient advertising campaigns. But is care by nurse practitioners and physician assistants really as good as that of physicians?

Imagine this scenario: There is a looming shortage of pilots in the nation, and experts expect that there will not be enough available pilots to fly the nearly 2 million Americans who want to board a domestic flight every day. It takes about two years and 1,500 flight hours for a pilot to be certified to fly commercially by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Imagine that instead of training additional pilots from scratch, the FAA decided to put flight attendants in the cockpit. The attendants would take an online course on aviation with flight simulations, and then spend 500 hours in the cockpit shadowing a certified pilot before they were permitted to fly independently. Statistically speaking, there is an extremely low chance of a plane crash, and if there are no complications or mishaps, the flight attendants should do just as well as the fully trained pilots. But if your flight were being flown by a pilot with little experience, would getting onboard really be as safe?

A similar scenario is playing out in hospitals and clinics across our nation. Patients are being treated by practitioners with just a fraction of the training of physicians, and few are questioning whether this care is safe or effective. Americans should be every bit as concerned about their safety when they enter medical care as when they board an airplane. After all, more people receive medical care than fly in this country, with the Centers for Disease Control estimating that almost 85% of American adultsabout 213 million peoplehave had contact with a healthcare professional in the past year.

Next page