THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES

MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Editorial Board

Alton L. Becker

Peter E. Hook

Karl L. Hutterer

John Musgrave

Nicholas Dirks, Chair

Ann Arbor, Michigan

USA

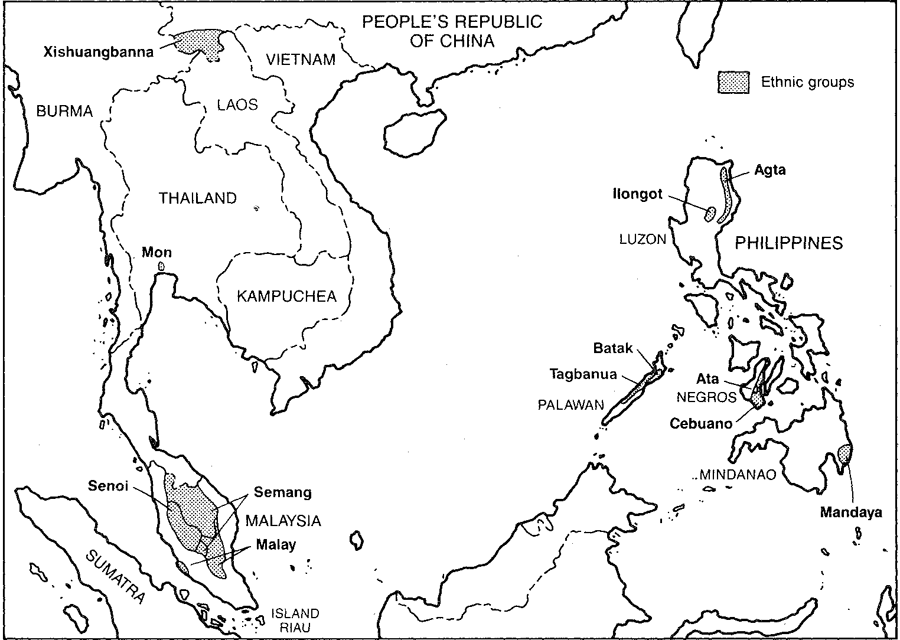

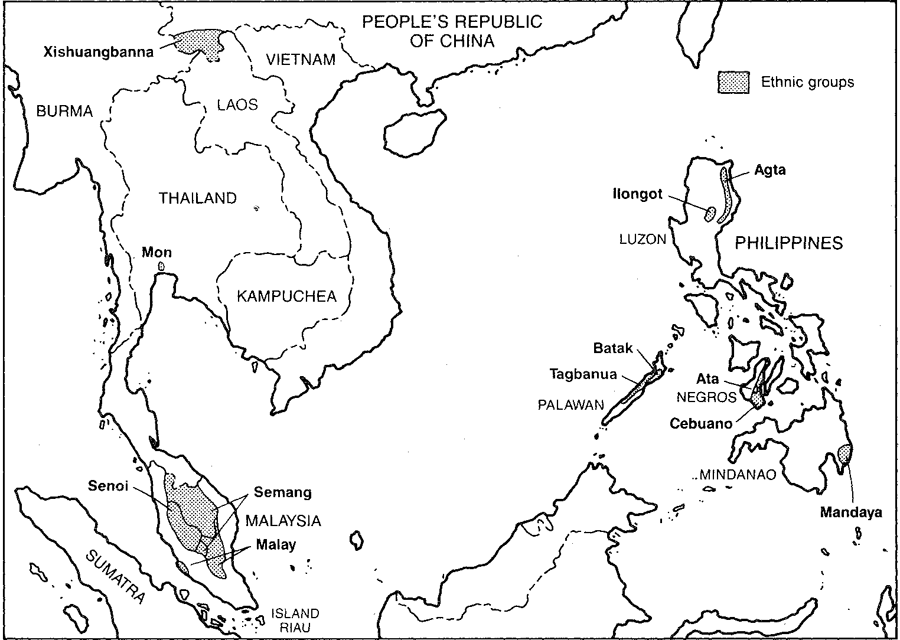

Location of groups discussed in this volume (drawn by K. Gillogly)

ETHNIC DIVERSITY AND THE CONTROL OF NATURAL RESOURCES IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

edited by A. Terry Rambo, Kathleen Gillogly, and Karl L. Hutterer

Published in cooperation with the East-West Center, Environment and Policy Institute, Honolulu, Hawaii

MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA

CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

NUMBER 32

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 87-62020

ISBN: 0-89148-043-9 (cloth)

ISBN: 0-89148-044-7 (paper)

Copyright 1988

Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies

The University of Michigan

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89148-043-3 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-89148-044-0 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12830-3 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90230-9 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

To the memory of Dawn Jean Rambo

CONTENTS

A. Terry Rambo, Karl L. Hutterer, and Kathleen Gillogly

A. Terry Rambo

James F. Eder

Rome V. Cadelia

Robert L. Winzeler

Alberto G. Gomes

Pei Sheng-ji

Brian L. Foster

Renato Rosaldo

Aram A. Yengoyan

Vivienne Wee

Maps

Figures

Tables

In August 1984, a three-day conference on ethnic diversity and the control of natural resources was held at the University of Michigan. Jointly sponsored by the Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies of the University of Michigan and the Environment and Policy Institute (EAPI) of the East-West Center in Honolulu, the conference was attended by fifteen scholars from six Asian and Pacific countries including the United States (see list of participants in the Appendix). This conference was the second in a series of conferences dealing with key issues in the human ecology of Southeast Asia jointly sponsored by the East-West Center and the University of Michigan. The proceedings of the first conference, held in Honolulu in 1983, have been published in Cultural Values and Human Ecology in Southeast Asia as Number 27 in the series Michigan Papers on South and Southeast Asia.

Like the first conference, which focused on the relationship between cultural values and tropical ecology, this meeting was planned to bring together Asian scholars working in member projects of the Southeast Asian Universities Agroecosystem Network (SUAN) with scholars in Western institutions who share their concern with developing human ecology research in the region. The purpose of the conference was to explore the ecological ramifications of ethnicity in Southeast Asia. This topic was chosen under the assumption that the high degree of ethnic diversity historically evident in the region and its continuing importance under contemporary conditions is related to both the nature of tropical Asian environments on the one hand, and the nature of Southeast Asian political systems and the ways in which they manipulate natural resources on the other. Although the emphasis of the conference series is on developing improved theoretical understandings of human-environment interactions, it should be evident that the topics selected for discussion also have great practical significance.

Scholars representing a broad range of theoretical perspectives and working with an even wider range of ethnic groups and environments were invited. This diversity is reflected in the resulting papers although, unfortunately, the range is narrower than it was in the conference itself. This reflects the fact that anumber of participants, for a variety of reasons outside the control of the editors, elected not to submit their papers for publication in this volume.

All the chapters have been significantly revised following the conference, in many cases taking alternative perspectives presented by other participants into account in the process. The editors have sought to impdse a common format while trying to preserve as much as possible the unique qualities of the individual papers.

Funding for the conference was provided by the East-West Center and the University of Michigan. Karen Ashitomi and Regina Gregory, EAPI Human Ecology Program secretaries, typed multiple drafts of the manuscripts. Helen Takeuchi was responsible for copyediting.

A. Terry Rambo

Karl L. Hutterer

Kathleen Gillogly

Its vast human diversityracial, linguistic, and culturalhas made Southeast Asia simultaneously the ethnographer's heaven and the ethnologist's purgatory. Simply describing the multitude of different peoples inhabiting the region has kept several generations of field workers gainfully employed, with results that threaten to swamp all but the largest library collections. As a consequence of this activity, it is fair to say that Southeast Asia is now at least as well known ethnographically as any world region with the exception of Native North America.

Unfortunately, ethnologists have not enjoyed great success in imposing classificatory order on the diversity revealed by the work of the ethnographers. The culture-area approach, still the standard framework for ordering New World ethnology, was not a conspicuous success when applied to Southeast Asia (Bacon 1946; Kroeber 1947; Narroll 1950). To dichotomize the multitudinous groups in the area into upland swidden farming tribesmen and lowland wet rice farming peasants (Burling 1965) radically oversimplifies reality. Attempts to retain complexity, as in the ethnolinguistic classification employed by LeBar, Hickey, and Musgrave (1964), lack any systematic basis for differentiating between groups. As Yengoyan points out in his chapter in this volume, ethnographers have tended to divide and subdivide groups into finer categories whose existence is highly suspect.

The ad hoc character of ethnic classifications in Southeast Asia reflects, in our view, the continuing theoretical underdevelopment of area studies. Rather than evolving out of a vigorous confrontation between ethnographic observations and general anthropological theory, as was the case in New World ethnological classifications, the schemes employed in Southeast Asia have usually been imported ones. Unlike the American culture-area classification schemes, which are based upon a complex set of theoretical explanations for ethnic differentiation (adaptation to common environmental factors within each area plus diffusion across area boundaries), most of the schemes employed in Southeast Asia have assumed that diversity is explainable in terms of a single cause. For a long time, migration and diffusion were invoked as the key explanatory factor; more recently, equally simplistic evolutionary models have begun to displace the culture-historical approach.