1xpert/adobe.stock.com

YOU LIVE YOUR LIFE tethered by gravity to the Earth. Every step brings you in contact with rock or soil, even if hidden by a veneer of macadam or floorboards. You may think youve escaped gravitys clutches when you lift off in an airplane, but any exhilaration is fleeting; within a few hours, gravity will win, and youll settle back onto terra firma.

Our attachment to the Earth extends well beyond gravity. The food you eat is made from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or oceans, along with water and nutrients taken up from soil or sea. With every breath you bring oxygen-rich air into your lungs, enabling you to gain energy from your dinner. At the same time, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere keeps you from freezing. Moreover, the steel in your refrigerator door, the aluminum in your tin cans, the copper in your pennies, and the rare-earth metals in your smartphone all come from within the Earth. Given all this, it is remarkable how incurious most of us are about this great sphere that sustains us and occasionally, during earthquakes or hurricanes, places us in harms way.

How can we understand Earths place in the universe? How did the rocks, air, and water that define our existence come to be? How do we explain our continents, mountains and valleys, earthquakes and volcanoes? What controls the composition of the atmosphere or of seawater? And how did the immense diversity of life all around us come to be? Perhaps most important, how are our own actions changing both Earth and life? In part these are questions of process, but they are also historical inquires, and thats the framework of this book.

This is a story about our home, the Earth, and the organisms that spread across its surface. Everything about the Earth is dynamic, ever changing despite common but false impressions of permanence. Boston, for example, has a temperate climate, with warm summers, cold winters, and moderate precipitation distributed more or less evenly throughout the year. The seasons are predictable and if, like me, youve been around for a few decades, you may get the feeling that youve seen it all before. Meteorologists, however, will tell you that the mean annual temperature in Boston has increased by more than a degree Fahrenheit (0.6 degree Celsius) during the lifetimes of its older citizens. We also know that the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmospherea major regulator of surface temperaturehas increased by about a third since the 1950s. Similarly, measurements tell us that global sea level is rising and the amount of oxygen dissolved in the oceans has declined by about 3 percent since the Beatles catapulted to fame.

Small changes add up through time. A plane flight from Boston to London lengthens by about one inch (2.5 centimeters) each year, as new seafloor slowly pushes North America and Europe apart. If we could run the tape backward, wed see that 200 million years ago, New England and Old England were part of a single continent, with rift valleys like those seen today in eastern Africa just beginning to initiate an ocean basin. On the longest timescales, Earths transformations are truly profound. For instance, free to roam on the early Earth, you would have suffocated quickly in our planets oxygen-free air.

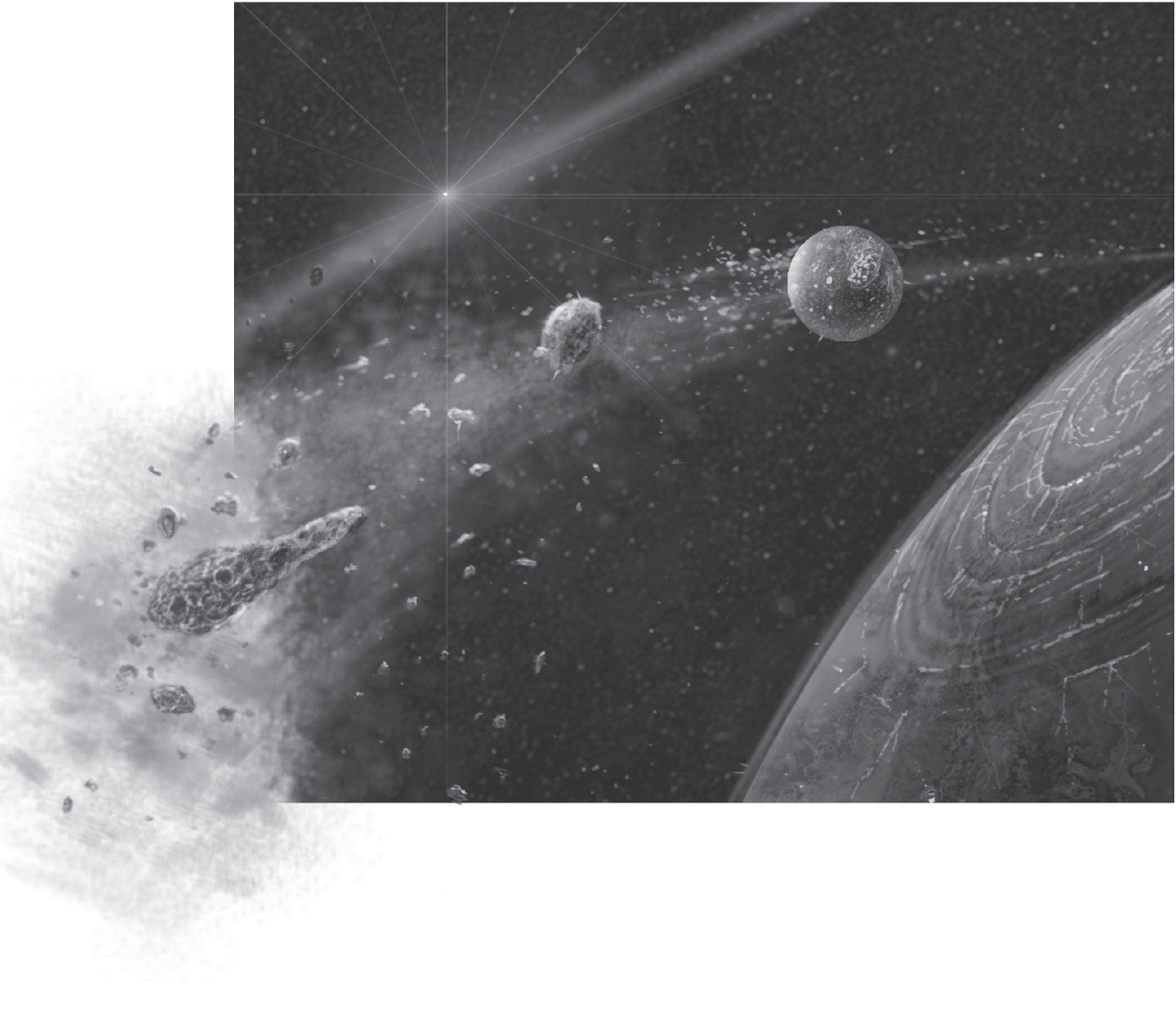

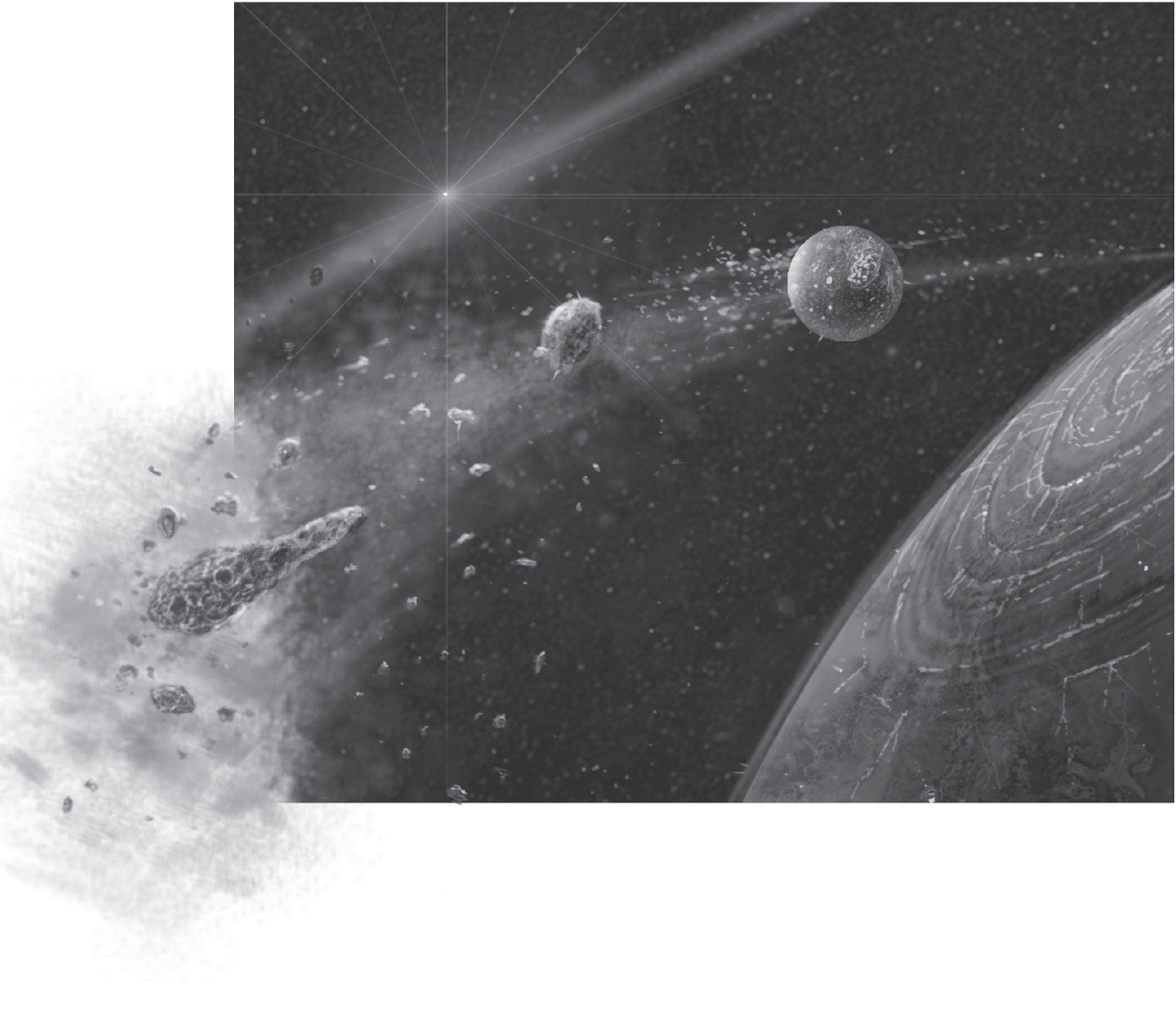

The story of Earth and the organisms it sustains is far grander than any Hollywood blockbuster, filled with enough plot twists to rival a bestselling thriller. More than four billion years ago, a small planet accreted out of rocky debris circling a modest young star. In its early years, Earth lived on the edge of cataclysm, bombarded by comets and meteors, while roiling magma oceans covered the surface and toxic gases choked the atmosphere. With time, however, the planet began to cool. Continents formed, only to be ripped apart and later collide, throwing up spectacular mountain ranges, most of which have been lost to time. Volcanoes a million times larger than anything ever witnessed by humans. Cycles of global glaciation. Countless lost worlds we are only beginning to piece together. Somehow on this dynamic stage, life established a foothold and eventually transformed our planets surface, paving the way for trilobites, dinosaurs, and a species that can speak, reflect, fashion tools, and, in the end, change the world again.

Understanding Earths history helps us appreciate how the mountains, oceans, trees, and animals around us came to be, not to mention gold, diamonds, coal, oil, and the very air we breathe. And in so doing, our planets story provides the context needed to grasp how human activities are transforming the world in the twenty-first century. For most of its history, our home was inhospitable to humans, and indeed, among the enduring lessons of geology is a recognition of how fleeting, fragile, and precious our present moment is.

THESE DAYS , the headlines often seem to have been ripped from the book of Revelation: unprecedented wildfires in California and the Amazon aflame; record heat in Alaska and accelerating glacial melt in Greenland; giant hurricanes devastating the Caribbean and Gulf Coast, while hundred year floods inundate the American Midwest with increasing regularity; Chennai, Indias sixth-largest city, running out of water, with Cape Town and So Paulo coming close. The news from biology is hardly better: a 30 percent decline in North American bird populations since 1970; insect populations halved; massive coral mortality along the Great Barrier Reef; rapid declines of elephants and rhinos; commercial fisheries under threat around the world. Population decline is not extinction, but it is the road down which species travel on their way to biological endgame.

Has the world run amok? In a word, yes. And we know why: the culprit is us. It is humans who pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, not only warming the Earth but increasing the magnitude and frequency of heat waves, drought, and storms. And it is humans who have driven species to the brink through changing land use, overexploitation, and, increasingly, climate change. With this in mind, possibly the most depressing news of all is the human response: widespread indifference, perhaps especially in my home country, the United States of America.

Why do so many people care so little in the face of planetary changes that will reshape the lives of our grandchildren? In 1968, Baba Dioum, a Senegalese forest ranger, provided a memorable answer. In the end, he said, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.

This book, then, is an attempt at understanding. An invitation to appreciate the long history that has brought our planet to its present moment. An exhortation to recognize how profoundly human activities are altering a world four billion years in the making. And a challenge to do something about it.

1xpert/adobe.stock.com

MAKING A PLANET

Todd Marshall

IN THE BEGINNING WAS ... well... a jot, a speck, a fleck at once incomprehensibly small but unimaginably dense. It wasnt a localized concentration of stuff in the vast emptiness of the universe. It