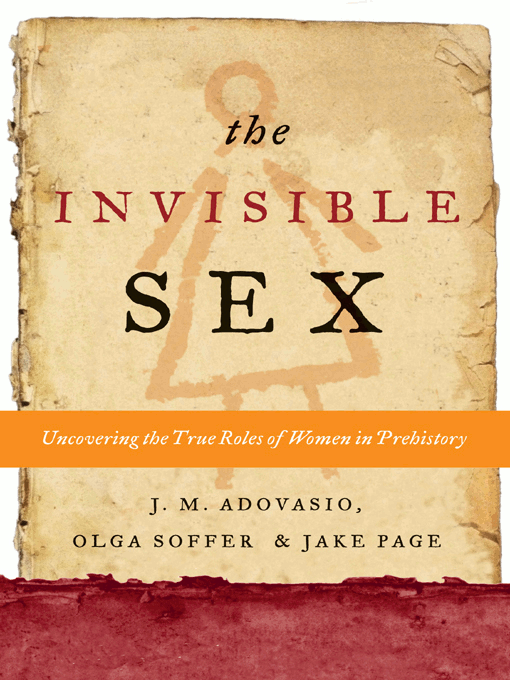

an outstanding Russian scholar, stimulating colleague, consummate charmer, and good friend, whose impact on Paleolithic archaeology was muted because of both her gender and her ethnicitya modern-day example of invisible sex at work in academia.

This book is the product of three authors, and that may well remind readers of the old caveat about too many chefs in one kitchen, which implies a culinary catastrophe. But numerous chefs are common in the arena of scientific discourse. Some scientific papers include the names of practically everyone who had anything to do with the experiment or investigation being describedprobably even the guy who delivers the pizza on late nights in the lab. In theory, everyone except maybe the pizza guy signs off on the wording of the final article, signaling an overall agreement with its contents. But this book is not a piece of scientific discourse like that.

We might never have known one another, much less worked together, except for a series of contingencies and serendipitous events. This is fitting, since the story we will tell here is also one of contingencies, of what might be called accidents. For example, the occasional mutation occurs in some apes genes, a mutation that does nothing to harm the creature and perhaps does something helpful. A slightly different ape emerges. Over a few million years, and a lot of mutational games of chance (most of which ended in TILT), here we are: humans.

In a similarly random manner did the three of us come together to produce this book.

Adovasio, whom we will refer to as Jim, was thrust by an extremely forceful archaeological professor into the extremely unsexy field of perishable artifactsbasketry, cordage, weaving, and so forth. These all fall into the category of perishable artifacts because they dont usually preserve well, and hence there arent very many to be studied. Before long he was the leading scholar on all such artifacts in North America and had handled, inspected, and thought about almost 90 percent of every such artifact known on the continent. This put him, as a regular duty of his profession, in mind of prehistoric women, since by analogy to living populations it was women who usually made such stuff. Also, by an accident (if you believe in such things), he became terribly controversial when, in the 1970s in the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in western Pennsylvania, he and his students came across evidence that people had trod North America some 5,000 or 6,000 years earlier than the evidence until then showed. This kicked up a terrible fuss, of course, which is just now dying down some 30 years later, with most American archaeologists admitting that people were here much earlier. But to substantiate his claim, Jim and his team invented some of the most rigorous field and laboratory procedures ever seen in the field of archaeology, including something called forensic microsedimentology, and it was this technical excellence that recommended him, it seems, to be invited to a historic pair of meetings of Soviet and American archaeologists in the early days of glasnost. One of the prime movers in these two meetings was Soffer, whom we will refer to as Olga.

Jim knew from the age of three or four that he wanted to be an archaeologist, but Olga had a stint in the fashion business first. Of Russian extraction and a native speaker of that language, she devoted most of her attention, starting in 1977, to the Paleolithic era in Soviet-dominated eastern Europe and central Europe. She also served as a scientific advisor to Jean Auel for two of her novels of the Pleistocene, Mammoth Hunters and Plains of Passage.

Since Marx had said nothing about the Paleolithic, the Soviet archaeologists could (and did) become friendly with Olga, and they all wanted to bridge the chasm that existed between Soviet and American colleagues. When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union, this aim could become a reality. Olga and George Frison, onetime head of the Society for American Archaeology, organized the first SovietAmerican Archaeological Symposium in the summer of 1989 when nine North American archaeologists traveled to the Soviet Union. Jim and Olga met for the first time in the departure lounge at JFK airport in New York. Jim spoke Ukrainian, learned from his mother, and when they arrived in the Soviet Union, he helped Olga with translating and with herding archaeologists around the country to visit various seminal sites. More than that, however, Jim had for 30 years been telling everyone in his field how important a diagnostic tool was to be found in all those perishable artifacts he had come to know so well. Nobody seemed to give a damnexcept that Olga did. Right off, perhaps in part because she was as attuned to fashion as she was to ancient ceramics, she also took up the cause.

A second symposium took place in Denver in 1991, in part financed by Jean Auel, who had become a kind of archaeology angel. Later that year, Olga and some colleagues were planning the excavation of a site in the Ukraine and asked the Ukrainian-speaking and technically proficient Jim if he would like to come along. He did. Later, in 1995, at a meeting about the Ukrainian site in Olgas home in Urbana, Illinois, she showed Jim some slides of enigmatic impressions she had taken while working on another project in Moravia in the Czech Republic. There she had been looking at a huge collection of fired clay from some 26,000 years agoat the time thought to be the oldest pottery known anywhereand had photographed some that had what looked like parallel lines on them.

She projected the slides on the refrigerator door. Jim announced that the lines were the impressions of textiles, making them by far the earliest such artifacts. Olga and another colleague wondered whether he was not mistaking the texture of the refrigerator door as textiles, and Jim gave them a look that nearly turned them into pillars of stone. So the Paleolithic Era (a.k.a. the Stone Age) got its first textiles, which play an important part in Chapter Eight of this book.

Meanwhile, not long after this historic meeting in the kitchen, Jake Page, a onetime science editor at Natural History and Smithsonian magazines and then a freelancer, had been given an assignment by Smithsonian to write an article about what was new in the archaeological pursuit of what was called Early Man in the New World. This necessitated a trip to Jims haunts at Meadowcroft, which led not to an article on the subject ( Smithsonian decided not to publish the article because they heard that the editor of National Geographic had one in the can) and then to a collaborative book called The First Americans.

So, when the idea arose for a book on the female side of human evolution and prehistory, it made sense to take advantage of all these earlier contingencies, all this serendipity. Or, as we have joked on at least one occasion, perhaps given so many coincidences, a cabal of Paleolithic Venuses got sick and tired of being thought of as either madonnas or whores, and imperceptibly pushed us towell, none of us really believes in that kind of thing.