Names: Keller, Sarah (Sarah K.), author.

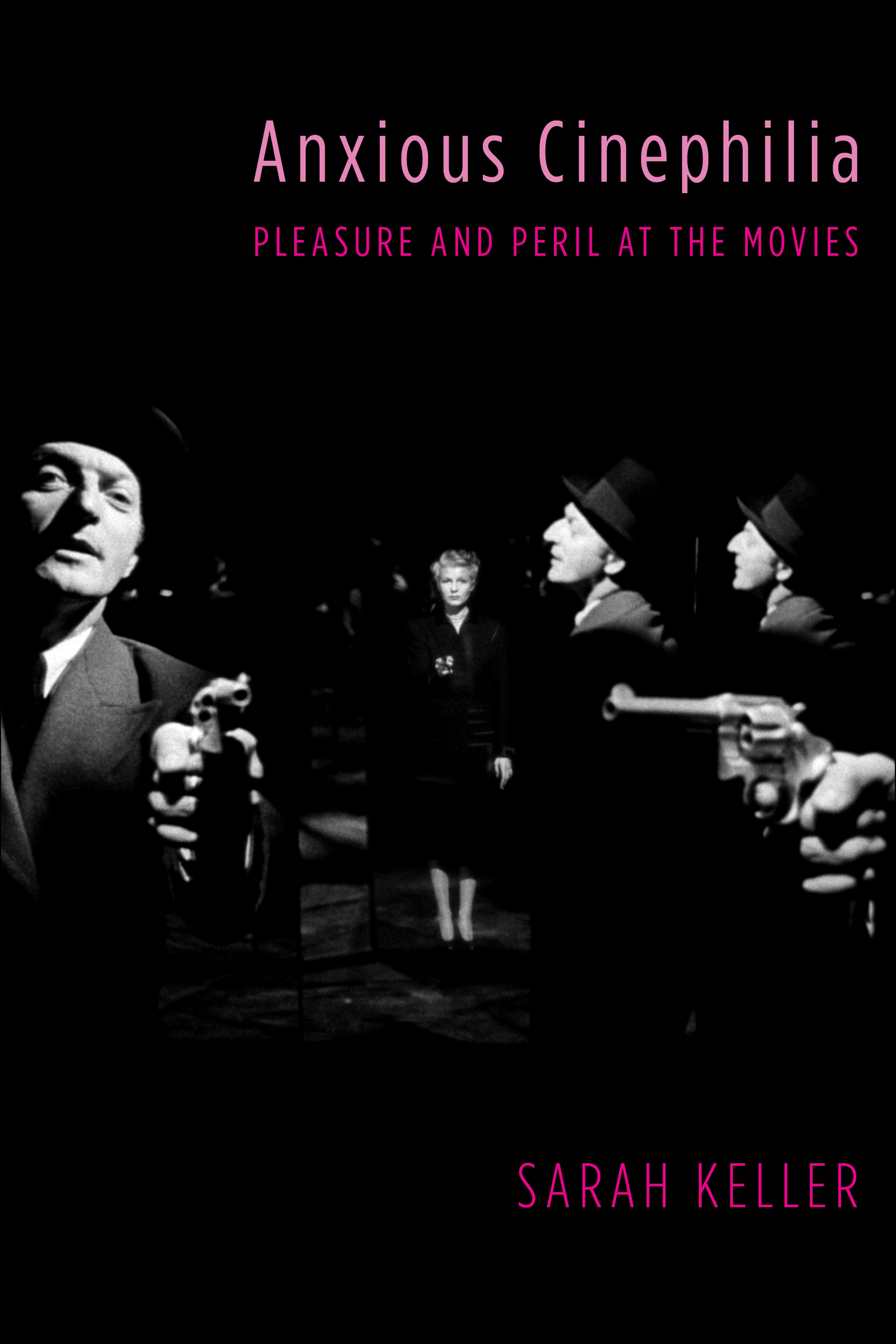

Title: Anxious cinephilia : pleasure and peril at the movies / Sarah Keller.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2020] | Series: Film and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019043044 (print) | LCCN 2019043045 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231180863 (hardback) | ISBN 9780231180870 (trade paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesAppreciation. | Motion picturesPsychological aspects. | Motion picturesHistory.

Classification: LCC PN1995 .K397 2020 (print) | LCC PN1995 (ebook) | DDC 791.4301/5dc23

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

I have profited from many conversations with all the smart, engaged, anxious cinelovers I know over the years I have worked on this project. I am deeply grateful to be part of that community. The conferences, panels, seminars, and individual invitations to present my work allowed me to air parts of this project. Thanks in particular to the organizers and audiences who offered thoughts at presentations for Domitor, Michigan State University, the Modernist Studies Association, New York University, Northwestern University, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, the Screen conference, and the University of Minnesota.

Thanks as well to the staff at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Beverly Hills, California, who assisted me in finding and copying materials in their collection about colorization and the impact of movies on youth.

I owe a special thanks to colleagues at New York Universitys graduate program in cinema studies during the time I spent visiting in 2013, especially Dan Streible, who set me up for success while there. That year, I taught a graduate seminar, Cinephilia/Cinephobia, where the spark of ideas related to this book began to catch fire. The students in that seminar influenced my thinking about cinephilia in highly productive ways, and I thank them for a great semester.

Colleagues from the University of Massachusetts at Bostonespecially in the College of Liberal Arts Deans Office, the Art Department, the Cinema Studies Program, and Healey Libraryalso provided a great deal of support as this project came into being. None did so more than Katharina Loew, who is the very best of interlocutors, writing partners, co-conspirators, and friends.

A special thanks, too, to Ariel Rogers, who at more than one point while I was writing this manuscript lent her calm, brilliant, incisive skills as a reader and editor. I would have been lost without her generous willingness to help. I deeply appreciate her kind encouragement and keen eye.

Others who also offered an ear, advice, suggestions for interesting things to look into further, a forum for presenting work, or general encouragement at crucial moments include Dudley Andrew, Nico Baumbach, Francesco Casetti, Don Crafton, Noam Elcott, Jennifer Fay, Ally Field, David Gerstner, Tom Gunning, Barbara Hammer, Maggie Hennefeld, Brian Jacobson, Daria Khitrova, Antonia Lant, Adrian Martin, Dan Morgan, Justus Nieland, Tasha Oren, Kate Rennebohm, Theresa Scandiffio, Girish Shambu, Tess Takahashi, Yuri Tsivian, Julie Turnock, Malcolm Turvey, Christophe Wall-Romana, Haidee Wasson, Patricia White, Jennifer Wild, and Josh Yumibe.

The Film and Culture series editor John Belton as well as Jennifer Crewe and Philip Leventhal at Columbia University Press provided guidance and thoughtful insights at key moments: I am grateful for their steadfast support. They expertly shepherded this project to its resolution, in part by also finding excellent, anonymous outside reviewers, whose comments sharpened this manuscript in important ways.

Thanks to cinemait has been a long-standing love that has sustained me for my whole life.

And first and last, thanks to my extended family and especially to my fellow cinephiles J, G, and Hfor simply everything. You made the time during which I worked on this book not only worthwhile but wonderful. I wouldnt have done it without you.

Simply put, cinephilia is the love of cinema. However, like all kinds of love, there is in fact nothing simple about it. An affectively driven response to the cinemaitself a fleeting, ever-changing phenomenon based on movementcinephilia is characterized, like love, by an attitude of volatility. Just as for love and cinema, cinephilia is not one thing for all people. So: how to fix this wave upon the sand?

What follows here pursues elusive objects and affects. It takes as its starting point the notion that the foundation of cinema upon which cinephilia builds has been laid with a fluid cornerstone: although it has enduring, sturdy elements that cohere into a system we call cinema, that system is an oceanic phenomenon in constant motion. Predicated on constant change in its ontological bases, its technological realities, and its position as part of cultural, historical, theoretical, aesthetic, economic, and social networks, cinema is naught if not on the move. And cinemas shifting circumstances will undoubtedly change yet again in wholly unforeseen ways in the future. The volatile nature of cinema leads naturally to volatile relationships with cinema. That is, cinema is a mercurial medium, and its magic, such as it is, depends on fickle spectators who watch and obsess in different ways.

FIGURE. 0.1 Six et demi, onze / 611 (Jean Epstein, 1927).

Cinephilia has often been treated as a specifically historical phenomenon, albeit one with threads that reach into earlier and later moments. Fixated in particular on French postwar, Cahiers du cinma, New Wave, auteurist milieus, this model of cinephilia has had a lasting impact far beyond that time and place. Historical notions of cinephilia persist, and they have indelibly and intensely shaped the way we understand film history, the role of directors, the notion of masterpieces, and the appropriate manner of appreciation for engaging with moving images. Indeed, these historical notionsoften not altogether unfairly charged with being elitist (the very word cinephilia may need to be defined to the layperson)have defined for better or worse hegemonic modalities of film style, production, and critical spectatorship. As a result of the way we tend to value certain films and filmmakers over others, the power to produce work has remained in certain demographics, and critical and theoretical ideas about cinema have been formulated from a certain kind of cinephilia. Cinephilia carries a political charge whether it originally meant to or not. Acknowledging cinemas fundamental mutability on the ontological level as well as on the phenomenological level sharpens the acuity of ones loveand ones love helpfully sustains and sharpens notions about what the cinema comprises and why it deserves love.