HELM

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

This electronic edition published in 2020 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, HELM and the Helm logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the UK in 2020

Copyright Lukas Jenni & Raffael Winkler, 2020

Lukas Jenni & Raffael Winkler have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as Authors of this work

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7722-9 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7723-6 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-7720-5 (ePDF)

Design by Marcel Burkhardt and Tabea Klliker

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

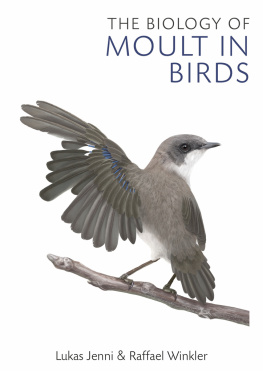

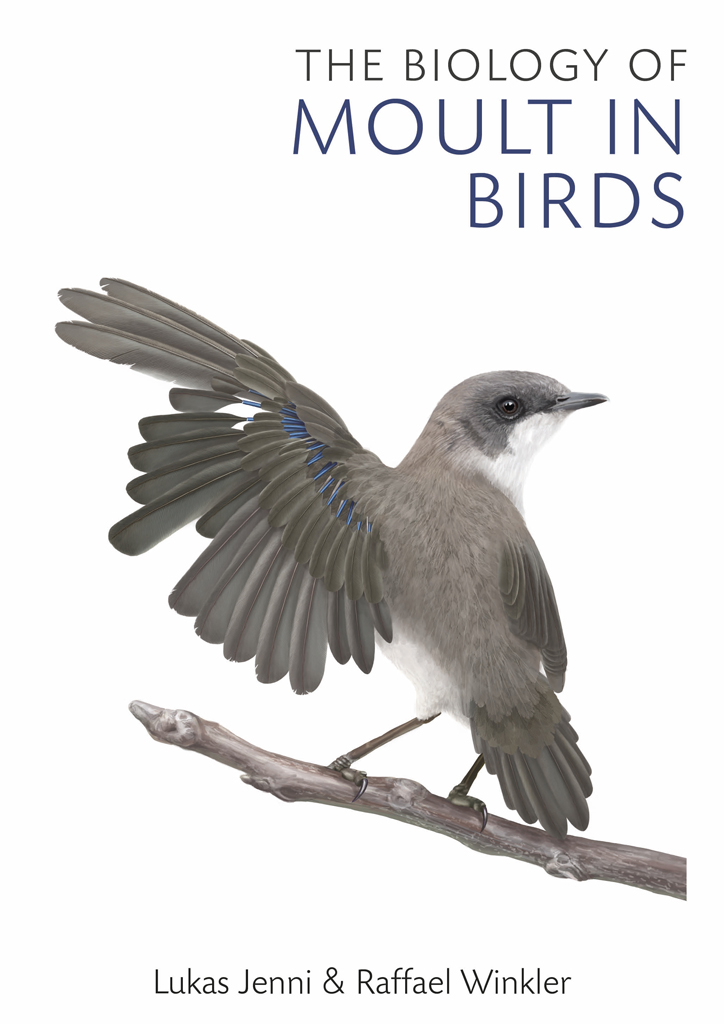

Cover drawing by Jasmin Hegetschweiler. It shows an adult Lesser Whitethroat Sylvia curruca in the middle of its complete moult. Primaries 1 to 6 (counted from inside to outside) and their primary coverts have been shed sequentially and are regrowing in a staggered order, the innermost being almost full grown, with a trace of sheath remaining at its base. Primaries 7 to 10 and their primary coverts 7 to 9 are still old, and are worn and bleached, as are the three unshed alula feathers. Secondaries 1 (the outermost) and 7 to 9 (the tertials) are growing, while secondaries 2 to 6 are old and worn. The greater coverts are all growing simultaneously, and all of the rectrices are growing in a staggered fashion. The blueish blood quills are only visible on the wing, while those on the body are covered by old and new feathers. The same bird is depicted in , where all the blood quills protruding from the skin are represented as though visible through the overlying feathers.

Contents

Preface

Moult in birds is a fascinating phenomenon. It is a basic life-history event which lasts for 13 months, or longer, each year and profoundly affects the physiology and behaviour of a bird. Moult is a period of physical maintenance and tissue renewal, not only of the plumage but also of other bodily structures. The challenges of moult probably equal those of reproduction and migration. Moult also affects many aspects of a birds life outside the moult period. For example, each moult determines the appearance of an individual bird anew and may change its plumage functions. Moult has a profound influence on the organization of the annual cycle, and constrains reproduction and migration.

Given these major impacts on a birds life, moult is a neglected field of study. During our research for this overview of moult, it was possible to examine most of the relevant literature, something that would have been impossible for other topics such as breeding or migration. Other signs of the underappreciation of moult are the rarity of symposia on moult at scientific congresses, and the lack of any moult working groups or congresses devoted to moult.

Even today, some treatises on bird families omit moult as a subject. More frequently, there is no consideration of the effects of moult on other aspects of bird biology (e.g. reproduction, immunocompetence) or on the determination of plumage traits, most notably in the context of sexual and social selection. In fact, the conditions during every moult, and how a bird copes with them, constantly determine a birds appearance. For instance, we were surprised that we could not a find a study into how the Indian Peacock produces its train one of the showpieces of sexually selected traits and what factors affect its quality. Astonishingly, the fact that both physiological and environmental conditions during moult affect the quality of the feathers produced seems to be largely neglected. For this reason we devote two chapters to the effects of moult, one dealing with its impact during the moult period ().

The study of moult and its effects on the biology of birds appears to be one of the last broad fields in ornithology where fundamental discoveries and insights can still be made. The study of moult started with descriptions of the timing and sequence of moult observed in shot birds in museum collections (e.g. Meves 1855, Altum 1875, Gerbe 1877, Stone 1896, Heinroth 1898, Dwight 1900, Miller 1928). Its first aims were to determine which changes in plumage were due to moult and which were not which moult patterns are phylogenetically inherited and which can be interpreted as ecological adaptation. The German biologist Oskar Heinroth hand-reared a large number of species in his apartment in Berlin and was able to study the sequence of moults in individual birds in detail and ask questions about the function, ecological adaptations, physiology and regulation of moult (Heinroth 1917, Heinroth & Heinroth 19241933, Heinroth 1931), work that was soon followed by the early studies on the effect of hormones on moult (summarized in e.g. Assenmacher 1958, Voitkevich 1966).

Oskar Heinroth stimulated Erwin Stresemann, also resident in Berlin, to pursue further moult research in his early career with the aim of discovering phylogenetic relationships (see Schulze-Hagen 2019). After a break of 40 years, Stresemann and his wife Vesta turned again to moult in 1960 and examined well over 50,000 museum skins, mostly non-passerines (summarized in Stresemann & Stresemann 1966), with the conclusion that the variety of moult patterns is not very helpful in revealing phylogenetic relationships. The Stresemanns work certainly persuaded several ornithologists in Germany and elsewhere to investigate various aspects of moult. The comparative description of the timing and sequence of moult was advanced by the development of a standardized moult recording card (see Jenni & Winkler 2020) for use by volunteer ringers (see Ginn & Melville 1983 for a concise summary for the UK). Moult patterns were also increasingly used for ageing birds, with the best known example for Europe being the several editions of Svenssons Identification Guide (the first in 1964, the latest in 1992).

With various physiological and ecological questions in mind, detailed descriptions of the moult of particular species followed (e.g. Newton 1966, Zeidler 1966). We also benefited greatly from the work of Ernst Sutter (19141999), one of the very first radar ornithologists, who worked meticulously on several difficult problems in moult, in particular serial moults, and who developed the wonderful collection at the Natural History Museum, Basel. Research on the physiology and regulation of moult also intensified (e.g. early work summarized in Dolnik & Gavrilov 1979, King 1980). The regulation of moult and its integration into the annual cycle was investigated by complementary field and laboratory research on passerines (for example the early work of Gwinner 1968, 1969, Berthold et al.