Table of Contents

FOR MY FAMILY

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stopsat all

And sweetestin the Galeis heard

And sore must be the storm

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm

Ive heard it in the chillest land

And on the strangest Sea

Yet, never, in Extremity,

It asked a crumbof Me.

Emily Dickinson, Poem 254, ca. 1861

Introduction

ON AN AFTERNOON IN LATE SEPTEMBER, IN A BRISK PRAIRIE WIND, I WATCHED a bird Id never seen before, a bird that had strayed far from its usual skies a continent away. Nearly epic in memory, that day began my journey, though I didnt know it then. The journey would take years and retrieve many things: first among them the name of the bird I had watched and didnt knowan escaped parrot that didnt belong in Kansas.

Seeing this bird led me to learn ofand revereAmericas forgotten Carolina Parakeet, which once colored the sky like an atmosphere of gems, as one pioneer wrote. The more I learned of the Carolina Parakeets life, its extinction and its erasure from our memory, the more I wondered: How could we have lost and then forgotten so beautiful a bird? This book is, in part, an attempt to answer those questions and an effort to make certain that we never again forget this species nor the others of which I write.

For as I traveled to libraries and natural history museums on the trail of the vanished parakeet, I soon learned of other birds, other vanished lives: the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, the Heath Hen, the Passenger Pigeon, the Labrador Duck and the Great Auk.

Id been a birder for a few years at that point in my lifethe early 1990sand I remain one today. Enthusiastic and, most of the time, at least moderately competent. (You can spot this kind of birder when he or she is in a crowd of experts; were the ones who stay very quiet and will not venture a first identification for risk of mortifying embarrassment. You thought that was an immature Black-throated Blue Warbler? Puhleeze!) Despite my quiet enthusiasm for birds, I knew nothing about these birds. And why should I have known? I couldnt see them, couldnt add them to my life list. They wouldnt show up on the local Christmas Bird Counts. They were gone.

Their absences haunted me. I began to write. Nearly 10 years later, this book appears.

While most dedicated birders will pore over field guides to puzzle out the nuances of Little Brown Jobs (sparrows) or the maddening winter plumages of various gulls, Id sit at a library carrel looking at John James Audubons Birds of America. I would marvel at the improbably massive beak and almost pathetically tiny wings of the Great Auk or the spiffy black-and-white plumage of the mysterious Labrador Duck.

What had happened to these birds? And why? This book recounts the histories of six extinct North American birds, the stories of their lives and their demise, the stories of the people who killed the birds and those who tried to protect themsometimes the same people. This is a personal chronicle, in which I weave together these accounts with my attempts to understand themwhich led me to visit the places where these birds once lived and died. I take a journey into the past and emerge, sobered and saddened, but also fascinated. And resolved to grapple with hope in this environmentally complicated time: The birds taught me that we can learn from these losses, take comfort in what remains and redefine hope from wish to work. We can work to protect the still-astonishing nonhuman lives that have come to depend on us for patience and care.

Not only did these extinct birds inspire me to delve into and present their natural histories, they also revealed many surprising, compelling human stories. There is, among others, the tale of the painter who saw the last confirmed Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the United States (as its forest was being logged) and the heretofore untold account of how the last known wild Passenger Pigeon died. These and other stories dramatize our various relationships to the land and the sky.

This subject matter also demanded engagement in cultural contexts, the broader historical forces that hastened these extinctions. Logging. The millinery trade. Unregulated hunting. Bird collecting by amateurs and professionals. The stories of the Passenger Pigeon and the Heath Hen illustrate, for example, the story of nineteenth-century urbanization in America, with the attendant development of voracious, concentrated public marketsmarkets that, for several years, sold unbelievable quantities of wild birds.

Perhaps unlike a professional historian and more like the poet I have been, I have found myself drawn to the oddments, the margins, so that a cookbooks reference to Passenger Pigeon Pie looms as importantly in this book as, say, logging statistics. A settlers account of how Carolina Parakeets in sycamores reminded him of Christmas trees in Germanythat matters to memory as much as facts of biology.

The books concern with context continues to the present day, as scientists and others ponder the startling possibility that extinct creaturesincluding these birdsmight be reborn through the rapidly advancing science of cloning. Such a prospect looms, of course, because of technological advance, real and potential. We consider this possibility, though, within a modern culture still struggling to discover some semblance of balance with the nonhuman world.

So I have tried to write not only a natural history, but something morea chronicle at once personal and historical, a collection of factual narratives that engage where we stand now, in relation to the birds gone and the birds remaining. We may never restore vanished birds through the promise of cloning. That may remain a Hollywood fantasy. But we can restorewe can restorythese vanished birds to our consciousness. That can be an important act of recovery of the human spirit in the nonhuman world. I know I risk accusations of nostalgia (I do miss these birds) but anyone who sees the past as important territoryas a map for the present and the futurerisks that allegation. Curiosity began my journey, which led to regret, which brings me always to wonder and dedication.

The Carolina Parakeet

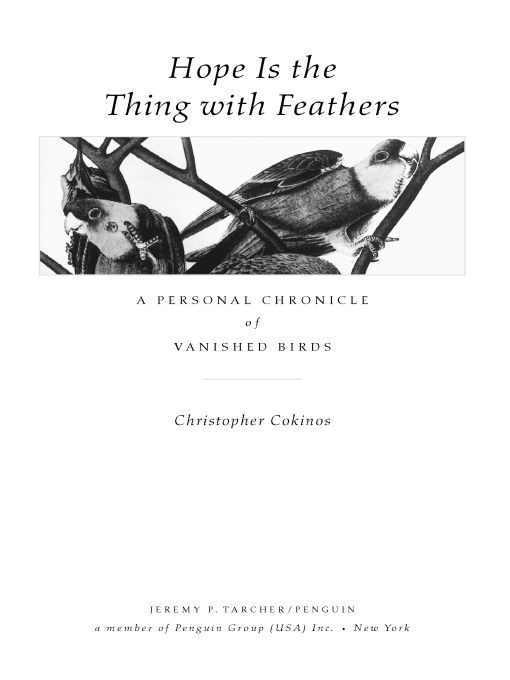

Overleaf: Carolina Parakeets feeding on cocklebur, by John James Audubon.

The Forgotten Parakeet

ON A BRIGHT, CLEAR, WINDY DAY, MY WIFE AND I DROVE TO A NEARBY LAKE. We recently had moved to the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas and, profoundly depressed, I yearned for southern Indiana, where we had been for several years, where we had become apprentices to the land, to still-beautiful fragments of hardwood forest. I disliked an office job Id taken soon after we had arrived in Kansas, as Elizabeth began her teaching career at a state university. I missed the magazine editing Id left behind. Also, I had a cold and felt, therefore, full of myself, literally and figuratively. A little anxious at my grimness, Elizabeth suspected that seeing birds would help. I blew my nose, dubious of nearly everything.