Copyright 2011 by Marlene Zuk

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zuk, M. (Marlene)

Sex on six legs / Marlene Zuk.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-15-101373-9

1. InsectsBehavior. 2. InsectsSexual behavior.

I. Title.

QL 496. Z 85 2011

595.715dc22 2010025829

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Lines from The Lives and Times of Archy and

Mehitabel by Don Marquis, copyright 1927,

1930, 1933, 1935, 1950 by Doubleday, a division

of Random House, Inc. Used by permission of

Doubleday, a Division of Random House, Inc.

Introduction

Life on Six Legs

Two-legged creatures we are supposed to love as we love ourselves. The four-legged, also, can come to seem pretty important. But six legs are too many from the human standpoint.

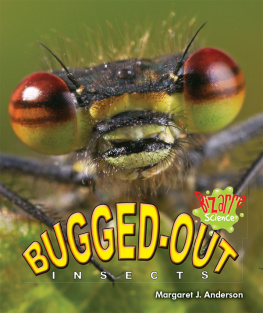

JOSEPH W. KRUTCH

P EOPLE are more afraid of insects than they are of dying, at least if you believe a 1973 survey published in The Book of Lists. Only public speaking and heights exceeded the six-legged as sources of fear, although "financial problems" and "deep water" (presumably when one was immersed in it) tied with insects at number three. Dying came in at number six. I have no reason to expect that matters have changed much, and suspect that if spiders had been included with insects in the options, fear of the multilegged would have easily topped the chart. People have strong feelings about insects, and most of those feelings are negative.

And yet for centuries, some of the greatest minds in science have drawn inspiration from studying some of the smallest minds on earth. From Jean Henri Fabre to Charles Darwin to E. O. Wilson, naturalists have been fascinated by the lives of six-legged creatures that seem both frighteningly alien and uncannily familiar. Beetles and earwigs take care of their young, fireflies and crickets flash and chirp for mates, and ants construct elaborate societies, with internal politics that put the U.S. Congress to shame. And scientistsalong with many backyard naturalistskeep on wanting to tell their stories.

It's not just that we publish scholarly journal articles about insects, or use them in our laboratories. Insects are special. Rats and mice are useful scientific tools, too, but although we personify them in fairy tales or cartoons, rodents are just not as compelling as bugs. Birds are beautiful, and we admire them and write poetry about their song and grace, but they don't get under our skinliterally or figurativelythe way that insects do. When it comes to insects, we write about Life on a Little-Known Planet, with Bugs in the System. We muse about Little Creatures Who Run the World, and we're only partly joking. Those of us who study insects are passionate about them in a way that can seem incomprehensible to outsiders. People get why Jane Goodall loves chimps; they are less sanguine about my fondness for earwigs.

Some of it, of course, is the sheer magnitude of almost everything about insectsthey are more numerous than any other animal, making up over 80 percent of all species. Estimates of the number of kinds of insects vary wildly, because new ones are being discovered all the time, but there are at least a million, possibly as many as ten million, which means that you could have an "Insect of the Month" calendar and not need to re-use a species for well over eighty thousand years. Take that, pandas and kittens! At any one moment, say while you are reading this sentence, approximately ten quintillion (10,000,000,000,000,000,000) individual insects surround you in the world. All of that variety gives enormous scope for evolution to act upon. Think of all those species as possible ingredients for a menu in a vast natural restaurant. You can come up with a lot more living recipes with insects than with the paltry few thousand bird species out there. And then there is the sensationalism; nothing gets my students' attention like hearing about male honeybees' genitals exploding after sex, and everyone has shuddered over the female mantis eating her mate. Insects routinely do things that would put the most gruesome horror film to shame.

Of course, not everyone finds insects scary, The Book of Lists survey notwithstanding. Those books on insects find readers, the nature channels on TV often feature bugs, and in 2009 the London Zoo hosted a "Pestival," "celebrating insects in art, and the art of being an insect." It included art, lectures, discussions, and a celebration of all things entomological. It even featured a six-legged take on the recent death of pop star Michael Jackson: Japanese artist Noboru Tsubaki made a "Vegetable Wasp," described as "a kind of cocoon for Jackson to enable him to traverse between the world of the living and the dead." Whether this effort successfully put Jackson's spirit to rest or not, metamorphosis is a powerful, and not unwelcome, image for us noninsects to contemplate. When Isabella Rossellini made Green Porno, her series of short films on animal mating, she led off with insects: dragonfly, bee, mantis, housefly. They were compelling in a way that other animals are not.

So what is it that keeps us coming back to insects? Why do they inspire such strong emotions, and what can we learn about ourselves from watching their joint-legged lives? The newest discoveries in biology, about genomes and nerve cells and the evolutionary connections between them, are best revealed by insects. This book is my celebration of a world that is alien and familiar at the same time, an invitation to the latest news about insect lives. We are continuing to make extraordinary and important discoveries about insects, routinely even finding new species. I haven't seen Green Porno, but if the segment on dragonflies is up to date, it should include a shot of the male's jagged penis as it scoops out the sperm from a previous mate, replacing it with his own. Sperm competition, in which the sperm of multiple males battle inside a female's reproductive tract, was first discovered, and is best understood, in insects, and new aspects of it are being uncovered all the time.

Insects are even teaching us about mind control, and maybe even about consciousness itself. A tiny wasp called the emerald cockroach wasp can do what many renters cannot: direct the movements of a cockroach. The wasp does this not to rid a kitchen of scuttling invaders but to feed her brood. Many wasps provision their young by paralyzing other insects or spiders and carrying them back to the wasp's nest. The paralysis, as opposed to out and out killing of the prey, helps the prey stay fresh while the young wasp larva feasts on the flesh. Of course, paralyzed insects can't put themselves into the nest, so the wasp usually has to do all the heavy lifting, staggering under the weight of her groceries as she flies back to her young. Except, that is, in the case of the jewel wasp, so named for the glittery emerald sheen of her exoskeleton. The female wasp doesn't send the roach into an immobile stupor; instead, she makes it into a zombie via a judicious sting inside the roach's head, so that its nervous system, and legs, still function well enough to allow it to walk on its own. Then, as science writer Carl Zimmer describes, "The wasp takes hold of one of the roach's antennae and leads it, like a dog on a leash, to its doom."

For years scientists were mystified about the precision of this sinister manipulation of the nervous system. How could a single injection of venom manage to produce what neuroscientists Ram Gal and Frederic Libersat, from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel and the Universit de la Mditerrane in France, called "a living yet docile" victim? Finally, in 2010, through a series of meticulous manipulations of the cockroach nervous system, including a kind of wasp-mimicking injection at various sites along the collections of nerve cells in the head, the researchers demonstrated that the drive to walk in response to most stimuli is seated in a tiny cluster of cells called the subesophageal ganglia. By poisoning just this minuscule part of the nervous system, the wasp is able, in Gal and Libersat's words, "to 'hijack the cockroach's free will.'" Zimmer refers to the discovery as finding "the seat of the cockroach soul." I am not so sure I buy the idea that roaches have souls to be found, nor that free will is residing in all those cockroaches lucky enough to miss an encounter with a jewel wasp, but then I am not sure about either of those things in humans, either. But the finding illustrates one of the most enthralling aspects of insects: they make difficult-to-grasp concepts, for example, souls and free will, satisfyingly literal. If we can get to a roach's motivation to walk by throwing a monkey wrench into a couple of cells, can the ability to find motivations for human behaviors be far behind?

Next page