MERIDIAN

Crossing Aesthetics

Werner Hamacher

Editor

THE OFF-SCREEN

An Investigation of the Cinematic Frame

Eyal Peretz

Stanford University Press

Stanford California

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2017 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior

University. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9781503600720 (cloth)

ISBN 9781503601611 (electronic)

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10.9/13 Adobe Garamond

Contents

Illustrations

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Brussels, Belgium.

Triangle Film Corporation.

Triangle Film Corporation.

Triangle Film Corporation.

Triangle Film Corporation.

Nero Film AG.

NSDAP Reichspropagandaleitung Hauptabt.

Charles Chaplin Productions.

Warner Brothers.

Charles Chaplin Productions.

Henry Lehrman, Kid Auto Races at Venice, 1914. Keystone Film.

Charles Chaplin Productions.

Twentieth Century Fox.

Olympia Film GMBH.

THRESHOLD

The Unframing Image

Whats in a frame? Whats in the frame of a work of art? It is in the gap or the distance opening between these two questions, between the frames, that this book tries to find its place.

While we will mostly pay attention to the cinematic frame, cinema stands as a culminating and to an extent revolutionary moment of what we will try to understand as a general logic of framing that preoccupies the work of art in modernity, that is, the work of art as it has developed from the Renaissance to the present. The question regarding the modern work of art, the question indeed of its modernity and novelty, is to a large extent one of exploring, investigating, and experimenting or playing with a new kind of frame, a frame that unframes.

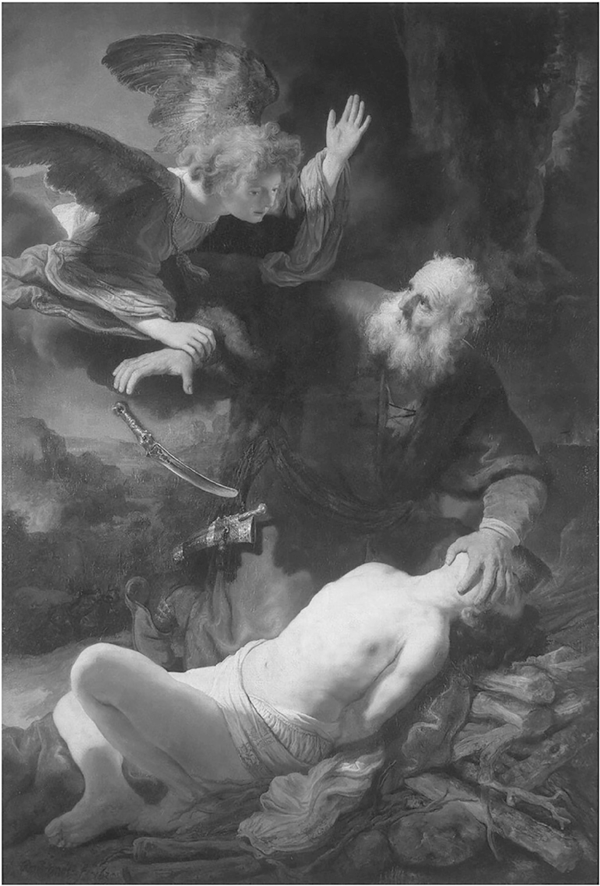

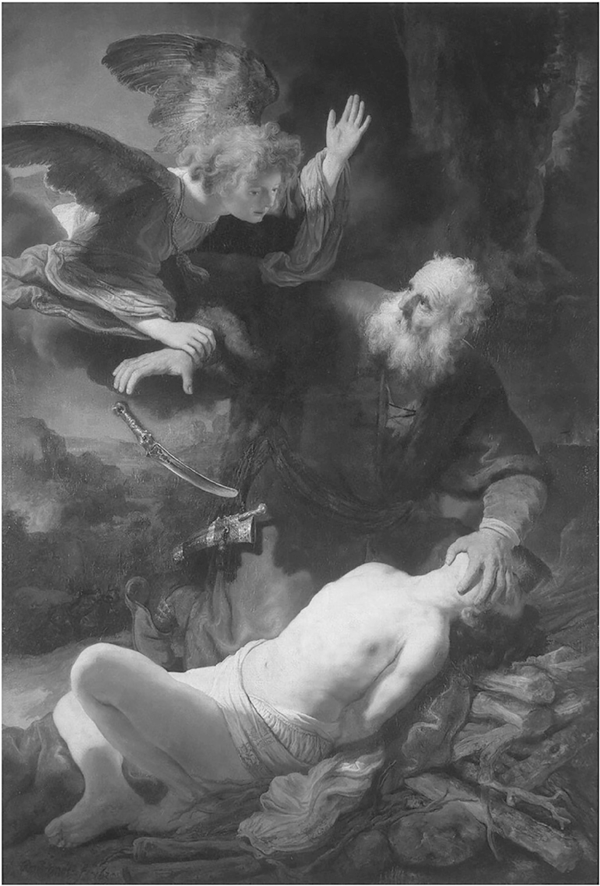

What does the frame of the modern work of art, the framing operation that is the modern work of art, unframe? This concern implicitly and explicitly guides my analysis. I will open by taking a look not at a film but rather a painting that strikes me as a remarkable allegorical reflection on this question of the frame. The painting is Rembrandts The Sacrifice of Isaac (1635).

The Interrupting Angel

All artists are escape artists. Because Rembrandt is a painter, he tries to paint his way out. If what one tries to escape is always a prison of sorts, then what is the prison here, and what are the means of escape? An inscription of a prison as well as an indication of the way out, the painting itself gives us the answers.

Looking at the painting, we can say that on the most literal level, that of representation, what we seem to have escaped, or more accurately, avoided at the last minute, is the killing of a son by his father, and what enables that escape is an interrupting angel. But what precisely does this mean? What is the nature of the killing, or sacrifice, of a son by his father? Why can we describe such a sacrificial scene as a prison? And what kind of escape does the interrupting angel offer? The key to all this can be found in the operation of the pictorial frame. By pictorial frame, I mean not simply the physical limitation of the paintings borders, but also the way in which what we see in the painting functions as the inside of a framing operation, an inside that organizes itself in relation to what we do not see, an outside of the frame.

The paintings theme, the angelic interruption of the sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham, is intimately tied here to the way Rembrandt understands the pictorial frame. In fact, this angelic interruption functions as an allegorical reflection on the activity of the painterly medium itself as structured by a new kind of framing operation, of a framing that unframes. I suggest that Rembrandt shows this new kind of frame to be a saving or interrupting angel. In other words, the angel is the painting: the modern medium of painting is an angelic interruption (of the sacrifice of a son by his father).

But what then, more precisely, is the angel? In the most immediate way, we can say that the angel is a messenger coming from the outside. In the case of the painting at hand, this outside is indicated, at the most obvious and basic level, as whatever is beyond the frames borders, for it is quite clear that the angel has just entered into the painting from a zone invisible to us. In fact, the tip of its wing is cut by the paintings frame, as if making explicit that it has just arrived from across the paintings border.

This outside, to begin with, is thus outside the frame. Yet things are not so simple, for this outside from which the angel comes is different from, say, the spatial outside, such as the wall on which the painting hangs or the outside that the paintings observers occupy. Rather, this outside of the frame seems to be a (nonspatial) part of the painting, belonging to something we might call the fictional realm of the painting (a realm that is larger or more than what the painting makes visible), an outside only made possible by, and in fact to a certain extent co-extensive with, the painting itself. It is the outside of the painting, both in the sense that it belongs to the painting and in the sense that it is outside any actual, visible part of the painting. Thus, while it belongs to the painting, it has no actual presence, only a presence we can understand, for lack of a better term, as virtual, and thus as a nonexistence that is nevertheless in effect. We can name such being-in-effect of what does not actually exist a haunting, a term that will play a prominent role in our discussions.

The achievement of this fictional realm of the painting depends on yet another aspect of the operation of the paintings frame besides its functioning as the marker of the borders of visibility. This other aspect is that of the frame as the mark of a separation or cut between the painting and its spatial and temporal surroundings, a separation emphasized by the paintings movability, by the fact that it can always be taken out of its present context and hung elsewhere. It is only because the painting is framed, in the sense of being cut out or separated from any specific surrounding, that it can create its own fictional realm, a realm in which a visible inside and an invisible outside, one that comes with the painting, wherever it moves, are copresent. It is this invisible outside belonging to the fictional realm that I shall designate as the dimension of the off.

We can see, then, that the paintings interruption of visibility and separation from its surroundings through its borders or frame are what allows the haunting invisible outside, the off, to become manifest: to appear as what is not actually present and visible in the painting yet is still part of it. Consequently, the appearance of the angel from the outside (an outside emphasized as being the outside of the frame) offers an allegory for the way the medium of painting, by creating a frame that cuts visibility, allows for an invisibility belonging to the painting to appear. The angel is the appearance of the medium itself, which makes ghostly invisibility visible; in other words, the angel stands for the being of the painterly image, which we can understand as the appearance of invisibility that belongs to the visible.

Next page