Contents

Guide

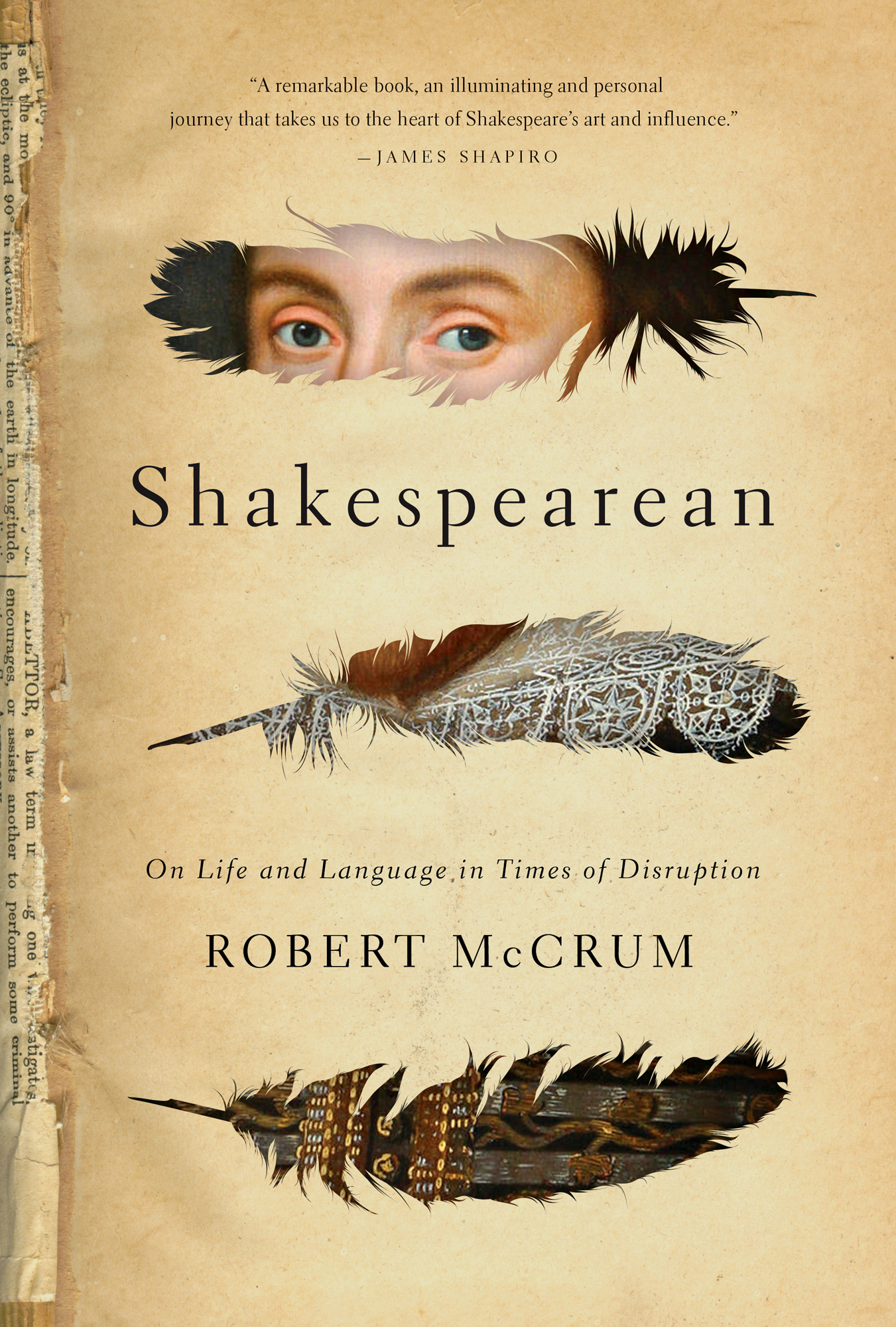

A remarkable book, an illuminating and personal journey that takes us to the heart of Shakespeares art and influence.

James Shapiro

Shakespearean

On Life and Language in Times of Disruption

Robert McCrum

For Emma

I hear new news every day, and those ordinary rumours of war, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, comets, spectrums, apparitions, of towns taken, cities besieged, daily musters and preparations, and such like, which these tempestuous times afford To-day we hear of new Lords and officers created, to-morrow of some great men deposed, and then again of fresh honours conferred; one is let loose, another imprisoned; one thrives, his neighbour turns bankrupt; now plenty, then again dearth and famine.

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621)

PART ONE, 15642016: Whos There?

Shakespeare then and now. How hes always modern, and why we turn to his book of life in years of crisis and disruption.

Prologue WAS THIS THE FACE?

The Portrait of a Young Man, 1585

1.

Through the darkness, under a brilliant spotlight, the enigmatic portrait of the anonymous young man glows like an icon in the dining hall of the Cambridge college where I grew up. After more scrutiny, this late-Tudor treasure, painted on wood, will furnish two dates Aetatis suae 21 Anno Domini 1585, the sitters age, plus the year in which he was posing and a sombre, transgressive motto, Quod me nutrit me detruit, meaning, That which nourishes me also destroys me.

The young mans costume is rich and fashionable, a gorgeous midnight-black velour doublet, cut to flash some peachy silk, and studded with exquisite gold buttons. His expression is confident but opaque. Pausing in front of this eye-catching scholar, we might be drawn to his face, framed by that androgynous mane of auburn hair. His lips are full and sensual. Do they express a smile? Possibly we are still guessing. Is there, in those dark-brown eyes, at once fearless and provocative, a challenge or an invitation? Perhaps he doesnt know, either. The shadow of his beard and that wispy moustache tells us hes barely out of adolescence. In the England of 1585, his inky costume alludes to Machiavellian thought, atheism and fashionable melancholy. Quod me nutrit me detruit. What unrequited love does this effeminate youth refer to? What existential torment? Who is he, and what are his circumstances?

Slowly, as we study this inscrutable image, he comes into focus as a university scholar, born in 1564, the same year as William Shakespeare. Further investigation, which now morphs into informed guesswork, even wishful thinking, yields an Elizabethan high-flyer, a godless poet, a homosexual, a secret agent and finally, a name.

The most famous playwright in Elizabethan England, Christopher Marlowe is still remembered for the lyrical rhetoric of Was this the face that launched a thousand ships?, and perhaps for revolutionizing English theatre. Familiar to Shakespeare and his contemporaries as Kit, he is the author of poems like The Passionate Shepherd to his Love, and plays such as Dr Faustus and The Jew of Malta. Yet, more than four centuries on, Marlowe and his work can seem as antique as oil-paint on wood.

This putative portrait is an image I grew up with. My father, Michael McCrum, was the senior tutor of Corpus Christi College when, in 1954, an undergraduate brought him some dusty pieces of scrap hed rescued from a skip, an obscure picture of a young man in sixteenth-century dress, which he thought might be of interest. Since Marlowe was born in 1564, my father later recalled, the dates fitted, and the Latin motto seemed appropriate. So it was possible that this was a portrait of the playwright, an alumnus of the college. We took the picture to our resident medievalist, who insisted that it should be cleaned and restored.

Since then, although there has been no further proof of identity, the picture, which hung for many years in the college hall, has become the accepted likeness of Christopher Marlowe. Its a haunting work of art, widely reproduced, that acts as a poignant reminder of a life cut short by sinister violence. Marlowes melancholy image also suggests a greater truth: namely, that the deeper we enter this singular universe, the more remote it becomes. Indeed, its chiefly the language and literature of Renaissance England which links us to a society so distant, strange and potent as to be simultaneously enthralling yet unknowable.

This anonymous portrait, which is almost contemporary with the year of Will Shakespeares hasty wedding to Anne Hathaway, provokes many questions. None is bigger than this: how is it that one sixteenth-century English writer no longer enjoys even a fraction of the acclaim he knew in his prime, while another continues to speak to us, from day to day, almost as our contemporary? Today, Marlowe and his work are familiar mainly to specialists. The dangerous aesthete, who is a perennial topic of conspiracy theory, remains a tantalizing source of academic speculation, whereas Shakespeare will always be Shakespeare.

2.

My question is: how did this happen? Why does Shakespeare live on as one of us, not merely in Britain, but across the globe? Posterity is fickle, and literary afterlives capricious, but Shakespeares universal fame is spectacular and unprecedented. What is his secret as a vibrant part of modern culture, as well as a touchstone of English, American, and even the worlds literature? How did a young man who grew up in rural Warwickshire, who did not go to university, who forged his early career paying Marlowe the sincere tribute of imitation, and who died at the age of fifty-two, far from court or cloister, become not merely Shakespeare but also the global icon for something far more influential: namely, that quality we call Shakespearean? What follows is a highly personal inquiry into the making, and perpetual remaking, of the greatest writer who ever lived, in relation to his time and our own. This investigation explores the paradox that, where Marlowe subordinated much of his art to his life and is remembered accordingly Shakespeare sublimated experience through art: in his plays, indeed, art and life become inextricable and timeless.

I will argue that today, in finding so many points of relevance and sympathy, we are closer than ever to Shakespeare and his world. His name conjures a universe of characters, poetry, scenes and ideas undergoing constant reinterpretation by audiences, actors and artists across the world, for more than four hundred years. Its through the dialogue of these incessant metamorphoses that, now more than ever, this Shakespeare is as much a part of our time as of his. Moreover, its as our contemporary that he remains modern, a writer with whom we inevitably engage, often not knowing precisely how or why. I am also concerned to examine the mystery of that transaction, by anatomizing the nature of the dialogue Shakespeare always sponsors with those, like me, who attend his plays or read his poetry, poised between the two worlds of then and now.

To write Shakespearean, I have immersed myself in the Elizabethan age of Marlowe and Shakespeare, although this remains a moving target. Pre-modern, and on the cusp of change, it does not always answer to the kinds of biographical inquiry we are used to. There are tantalizing gaps in the record of both lives, and in the many mysteries surrounding their work. Plays, players, and playwrights had neither the recognition nor the status they enjoy today. Yet both men left behind a treasure house of poetry and prose. Accordingly, I have grounded my argument in black and white the words on the page those surviving texts from a world now otherwise lost.