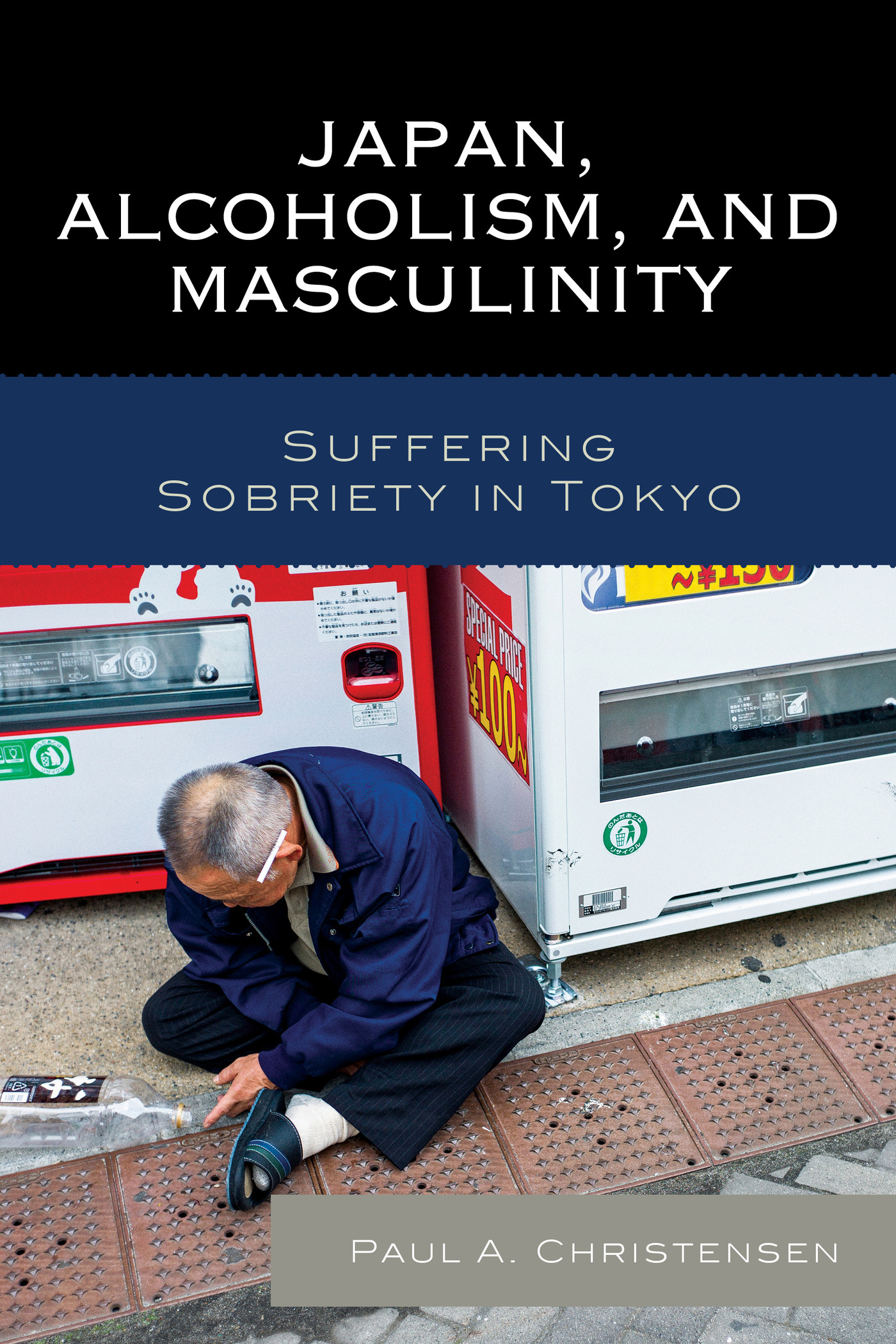

Japan, Alcoholism, and Masculinity

Japan, Alcoholism, and Masculinity

Suffering Sobriety in Tokyo

Paul A. Christensen

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

Writing about alcoholism, addiction, suffering, illness, loss, and the countless other afflictions that surround these topics is trying. Yet my struggles with gathering data, even when the subject matter was raw and unsettling, or fashioning that bulk of information into a coherent piece of scholarship, is nothing when compared to the struggles of the alcoholics introduced in the pages to follow. For this reason I owe an enormous debt to all the members of Alcoholics Anonymous, Danshkai, and the doctors and staff at the hospitals and clinics I visited in Tokyo, Kchi, Kagoshima, and other locales across Japan. Everyones unfailing patience and unhesitating assistance allowed me to write something I hope is insightful and valuable to Japans alcoholic community and beyond. Deepest thanks to the members of the Central Group, Ohashi Danshkai, and Kchi Danshkai, for graciously inviting me into your meetings and allowing me to observe all that transpired without reservation or hesitation. I can only hope to capture a degree of the emotion and power that transpired in those meetings. Finally, particular thanks to Aki, Yoshi, Gen, Toru, Masa, Hiroka, Yuka, Nakamura, Kazu, Toshi, and Ryota. Rarely have I met such an amazing collection of individuals who have overcome so much and work tirelessly every day in the service of others. Without your time, words and patience this book would not exist.

At the University of Hawaii I benefited tremendously from numerous friends and colleagues within and outside the Department of Anthropology and the Center for Japanese Studies. Christine Yano is the best doctoral advisor, friend, and academic mentor anyone could wish for. Sincerest thanks and mahalo as well to Ty Tengan, Eirik Saethre, Andy Arno, Deb Goebert, William Wood, Bob Huey, Gay Satsuma, Alex Golub, Geoff White, Eric Cunningham, Kelli Swazey, J.D. Baker, Hirofumi Katsuno, Satomi Fukutomi, Toru and Naomi Yamada, and Adam Lauer. Elsewhere, Laura Miller, Ted Bestor, Nicolas Sternsdorff, Merry White, Alvaro Jarrin, Linda Cool, Jennifer Matsue, Nancy Campbell, and Joyce Madancy all gave welcome and insightful comments and feedback on elements of the project. In Japan specific thanks to David Slater for his guidance and commitment to an intellectually vibrant anthropological community in Tokyo. Thanks as well to Anne Allison, Richard Chenhall, and Tomofumi Oka for insight and guidance while on the ground in Tokyo.

This work was supported initially through funding from the Monbukagakusho Scholarship, sponsored by the Government of Japan and administered in Hawaii through the Consul General of Japan at Honolulu and the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Hawaii. Later work was funded by the Association for Asian Studies and the Union College Faculty Research Fund. I remain flattered that so many saw merit in my work and helped foster its growth and development over the years.

My family has never wavered in their support along my long and winding path to an academic career. Mom, Dad, Amanda, Jonnie, Sam, Abby, Madilyn, Emma, Jackson, Lucy, Lucia, and AngelaI am so fortunate to have each of you, thank you for everything. Especially to my mom and dad, thank you for fostering an intellectual curiosity in all of us that even you might not fully realize. Finally, Ana and Caetano, the long process of taking this project from an idea to a book has coincided with much of our life together (plus one arrival!). You both are my inspiration and I love you immensely. Thank you for so much patience, help, and wonderful companionship.

Introduction

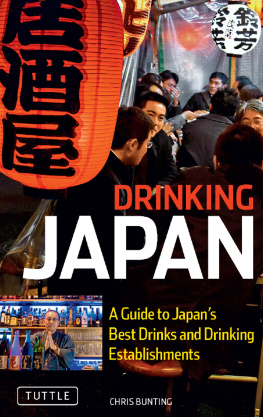

In August 1995, I was seventeen years old and working for the summer as an English teacher in Fukuoka, the major city on the southern Japanese island of Kysh. It was during this summer that I drank my first beer. I and the other teachers, high school students and undergraduates from Washington State and Wisconsin, were down to our final weekend after spending six weeks in Japan. Our collective thirst to do something we believed rebellious had peaked, so we ventured out into a warm Fukuoka evening armed with limited Japanese and the hazy knowledge that being under the legal drinking age in Japan (20) and the United States (21) mattered little, if at all. Despite our collective linguistic limitations, we managed to find Oyafuk-dori (the street of disrespectful children), with its expected wealth of drinking establishments. As mugs of beer arrived without incident and passports remained unchecked in pockets and purses we marveled at the casualness surrounding alcohol consumption in Japan and the impossibility of our sanctioned drinking upon return to the United States in a few days.

That evening I also took mental notes and blurry photographs to induce jealousy in my friends at home. I imagined their astonishment at vending machines that in exchange for a few coins spit out cold beer and sake. Although I did not consider it then, this was the first time I paid attention to the structures and patterns that surround drinking alcohol in Japan. Return trips in the ensuing years fed my growing interest in the topic, particularly how alcohol was consumed and regulated, as well as the surprising (at least to me) frequency with which the consequences of overconsumptionvomiting on train station platforms, public intoxication, and passing out almost anywherewere typically met with indifference, and perhaps a mop, from others.

Yet out of this early interest grew the gnawing feeling that an important component was missing from the prevailing perception of drinking in Japan, as if something had been left absent from the frame or positioned carefully outside the commonly perceived scene. While drinking is important in Japan, and there are many who have said why and how they think it is important, the unremarked position is that such a stance is rarely challenged or questioned. Drinking is everywhere in conversations about Japan, nonchalantly noted in popular and academic texts, films, and countless other accounts. As the only nation in the world where beer is widely available from vending machines, these same machines have earned ubiquitous mention in travel guides and other accounts of Japan by foreign observers. Yet the prominence of Japans alcohol consumption also renders it culturally banal to most, and the victim of trite conclusions by others. That first beer I had in Fukuoka did more than satisfy my thirst for youthful insolence, it set in motion a scholarly interest that in this book brings the backstage complexity surrounding drinking and, more importantly,

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.