Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

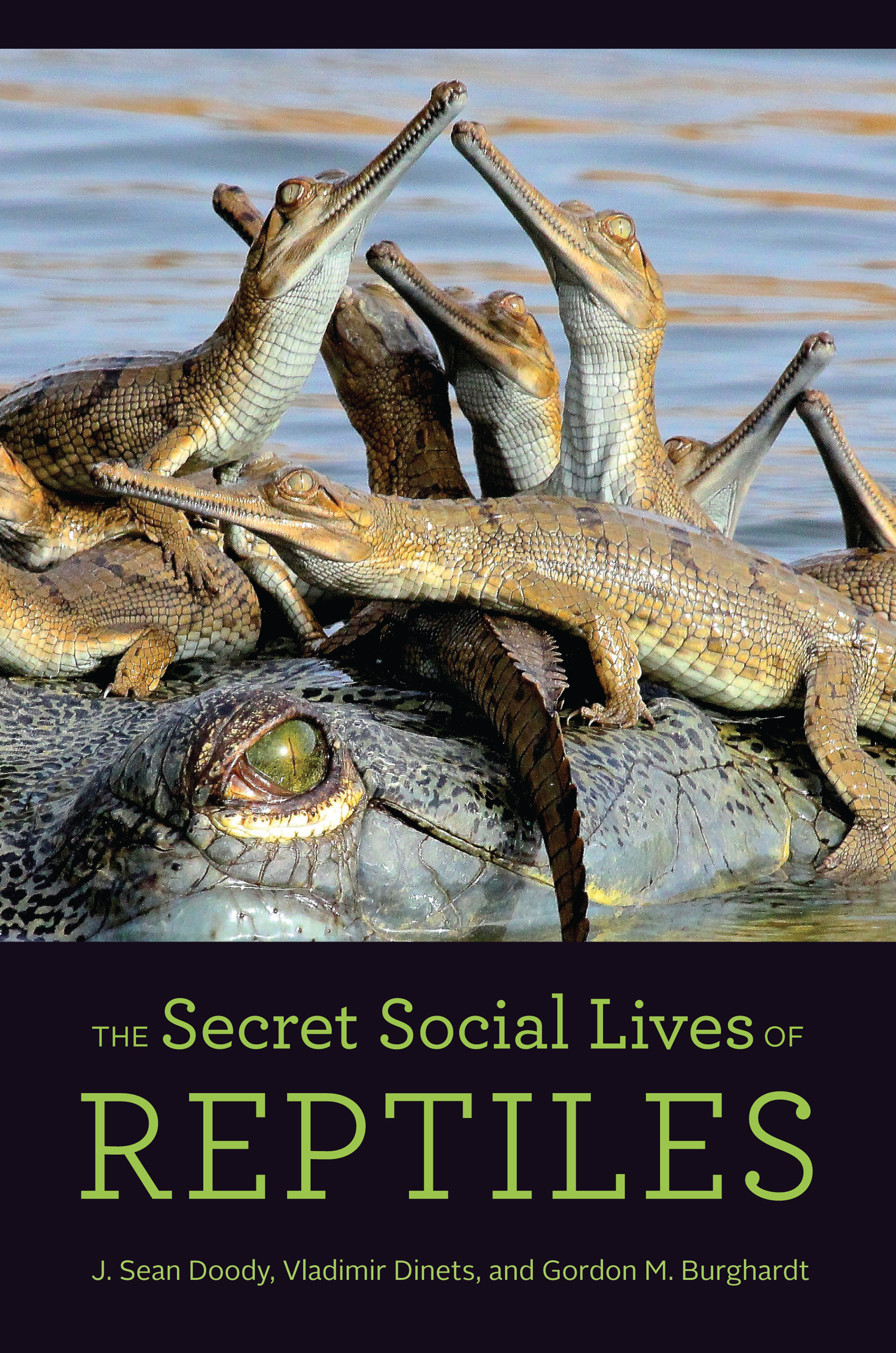

THE SECRET SOCIAL LIVES OF REPTILES

Secret Social Lives

REPTILES

J. Sean Doody, Vladimir Dinets & Gordon M. Burghardt

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESSBaltimore

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESSBaltimore

2021 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Doody, J. Sean, 1965 author. | Dinets, Vladimir, author. | Burghardt, Gordon M., 1941 author.

Title: The secret social lives of reptiles / J. Sean Doody, Vladimir Dinets, Gordon M. Burghardt.

Description: Baltimore, MD : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020028521 | ISBN 9781421440675 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781421440682 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ReptilesBehavior.

Classification: LCC QL669.5 .D66 2021 | DDC 597.9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028521

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

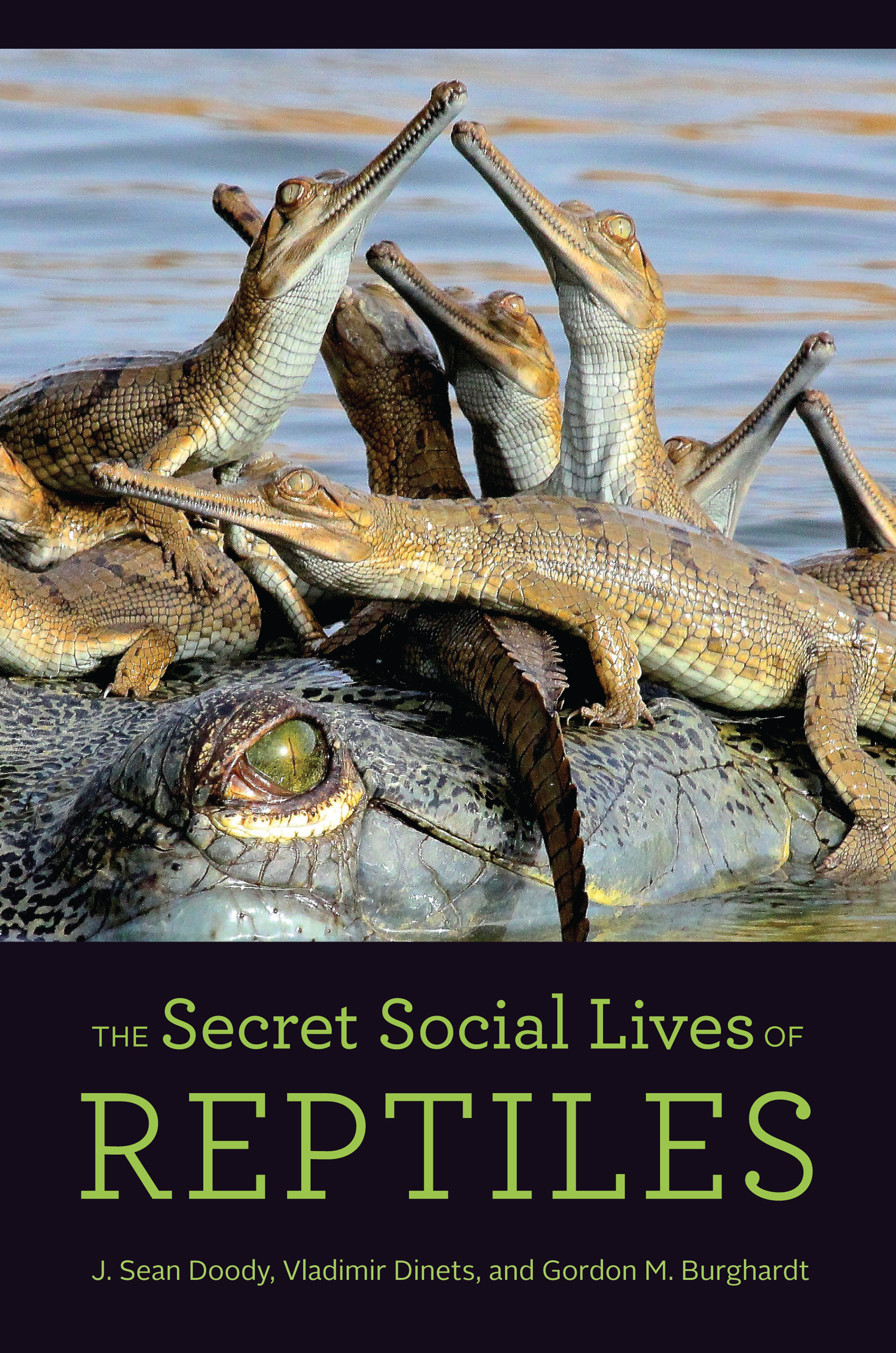

Frontispiece: Communal egg-laying in the giant Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis expansa) along the Purus River, Abufari Biological Reserve, Amazonas, Brazil. Photograph by Camila Ferrara.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at .

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

For Stan Rand

A pioneer whose foundational discoveries in herpetological social behavior and inspiring mentorship fed research streams through many diverse conceptual and geographical habitats

For Mike Bull

Whose ability to link broad concepts of natural history within the context of long-term research on reptiles left a legacy that we should embrace

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

What does it mean to be social? Members of a wolf pack stealthily hunting a wary elk, a flock of sandhill cranes migrating gracefully in formation in the crisp autumn sky, a mother wildebeest anxiously coaxing its calf to enter and cross a river, or even termites, in the many thousands, hastily working together to repair their damaged mound, all are activities we call social. Clearly, the sexual acts of humans, or of any other animal, are categorized as social. We keenly relate to all of these behaviors because we do them too. Remarkably, we express social behavior and have social lives in ways not unlike our close and distant relatives in the tree of life.

For a number of reasons, however, we have difficulty interpreting and relating to the activities of certain animals, such as reptilesin particular, non-avian reptiles (crocodylians, turtles, snakes, lizards, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara). Starting from one end of a continuum, I am fairly confident I could persuade most people, albeit with some effort, that a group of Cagles map turtles sun-basking on a log is an example of social behavior. Perhaps, that could be extended to a group of Nile crocodiles lounging on a river bank, waiting for prey. But, on the other end, I have serious doubts that I could be as persuasive when talking about a group of snakes (by the way, what is a group of snakes called?) or amphisbaenians, a close lizard relative that spends most of its life underground. With regard to the latter, my hunch is that most folks have never seen a photo of an amphisbaenian, let alone a live one indeed, most are unaware that this group of reptiles even exists. This navet or ignorance, a brand of intellectual poverty, is part and parcel of an ever-growing problem in our lack of understanding and appreciation of Earths tremendous biodiversity and its indispensable qualities (Greene, 2005, 2013; Wilson, 2009, 2014; McKeon et al., 2020).

Why do we distance ourselves from nature? Especially, why do we disconnect our lives from experiencing the full breadth of its biodiversity? Answers to these questions might give us better insights to my next question, the very basis of this book: why do we have difficulty perceiving reptiles as having complex social lives and other behavioral attributes, such as personality, reciprocity, and family? We regularly use these concepts and terms for mammals, birds, and even insects. Indeed, recent progress has been made in this field, but it is sparse. Warm-blooded chauvinism still abounds (Burghardt, 2020).

J. Sean Doody, Vladimir Dinets, and Gordon M. Burghardt, the authors of this important and captivating new book, enthusiastically, bravely, and masterfully tackle these questions, and many others, concerning the social lives of reptiles. In grappling with this imbalance of knowledge, the authors take us along on a wonderful intellectual journey.

Right off, the authors get to the core question: what is social behavior? They use the definition by Allaby (2009). Social behavior, broadly defined, is any interaction between two or more members of the same species. I like this simpler and direct approach because it relaxes the tight and restrictive grip of past definitions. It drops unnecessary jargon, and it makes clear that reptiles are social. Importantly, throughout the book, the authors break the socialnonsocial dichotomy (for example, social mammals and birds versus nonsocial reptiles) that has utterly paralyzed past research and progress. We now have a clean slate and are given permission to operate under a continuum of possibilities (Schuett et al., 2016).

Accordingly, with this robust platform, we become immersed in an array of ideas, questions, examples, and future research goals as they pertain to the social lives of reptiles. Proximate and ultimate questions concerning the ramifications of social behavior are carefully presented, and numerous examples are provided. Among them, and most intriguing to me, is the notion of reptile societies and social networks. I immediately envision a few obvious examples, marine iguanas, rattlesnakes, and the giant tortoises of the Galpagos (Krause & Ruxton, 2002). What about species that do not form permanent aggregationscan they form a society, however subtle? If so, do these societies have culture?

Using an evolutionary comparative framework, the authors present examples of social behavior of all groups of reptiles. Importantly, the early chapters provide the reader with an abundance of introductory information on the biology of reptiles pertinent to better understand social behavior. Evolutionary history, sensory anatomy and physiology, mating systems, and other topics all are discussed in a manner easy to comprehend.

Appreciating the diversity of social behavior of all organisms across the tree of life has far-reaching ramifications for humans. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have become painfully aware of the negative impacts of limiting social and physical contact. Isolation, especially long-term, can have enormous deleterious effects on individuals and, as we are seeing, our communities. Whether we like it or not, we have been abruptly awakened to a new era of social practices. We are redefining and readjusting our own social orbit and mores. To be certain, many studies will be conducted on the psychological effects of this global virus on our own species and how it influenced the social lives of nonhuman animals.

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESSBaltimore

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESSBaltimore