Aesthetic Ideology and the Bildungsroman

Preface

In a modest but ineluctable fashion, the specter of the Bildungsroman haunts literary criticism. This genre does not properly exist, and in a sense can be proved not to exist: one can take canonical definitions of Bildung (itself no simple term), go to the novels most frequently called Bildungsromane, and with greater or lesser difficulty show that they exceed, or fall short of, or call into question the process of Bildung which they purportedly serve. Even Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre can be (and has been) excluded from the genre it exemplifies. Nor does one need to be a postmodern literary theorist to encounter this paradox. Soundly humanistic Germanists have been doing so ever since the term Bildungsroman began to circulate in the early decades of the twentieth century (for another odd feature of this supposedly nineteenth-century genre is that its name barely appears in the literary record prior to the publication of Wilhelm Diltheys Experience and Poetry [1906]: its currency is roughly coterminous with the professionalization of academic literary study). Yet despite, or because of, its referential complexity, the notion of the Bildungsroman is one of academic criticisms most overwhelmingly successful inventions. Few professional terms (let alone German ones) have achieved comparable dissemination in Western literary culture; and critics probably will go on talking about the Bildungsroman as long as the institutions of literary criticism as we know them survive. The Bildungsroman exemplifies the ideological construction of literature by criticism.

In consequence, the issues raised by this pseudo genre greatly surpass the literal terms of the debate over whether it exists or not. My central argument in this book is that the notion of the Bildungsroman brings into sharp focus the promises and pitfalls of aesthetics, and that aesthetics in turn exemplifies what we call ideology. As a result, this book is not in the ordinary sense a book about the Bildungsroman. It is certainly a work of literary criticism and offers as central to its self-justification readings of novels by Goethe, George Eliot, and Flaubert. But since my analyses discover in the rather minor professional embarrassment of the Bildungsroman the infinitely inflatable question of the aesthetic, I am also writing about what we mean by culture, history, and humanity, what we do when we read or teach literature, and why the twentieth-century institutionalization of literature has generated the curious phenomenon of literary theory. In an indirect fashion this book is about the literary institution and thus also about the political, technical, and cultural worlds which this institution at once excludes and commemorates. This breadth of ambition stems from the peculiar difficulties of writing about aesthetic ideology.

Few narratives are more familiar to scholars of modern literature and culture than the story of the appearance of aesthetics, both as a new philosophical category and as a massively diffuse and influential discourseone that provided the post-Romantic Western world with meanings for words such as culture and art that we now consider primary. The topic of beauty is as old as philosophy, but the notion of the aesthetic as a particular sort of experience or judgment or class of objects does not begin to appear regularly until the eighteenth century. At the same time, large-scale historical developments were permitting, as is well known, the emergence of art and literature in their modern sense, and the transformation of the artist into the genius, the representative of universal humanity, whose productions transcend the system of commodity exchange which enables them. Aesthetics partakes of the emergence of the universal subject of bourgeois ideology.

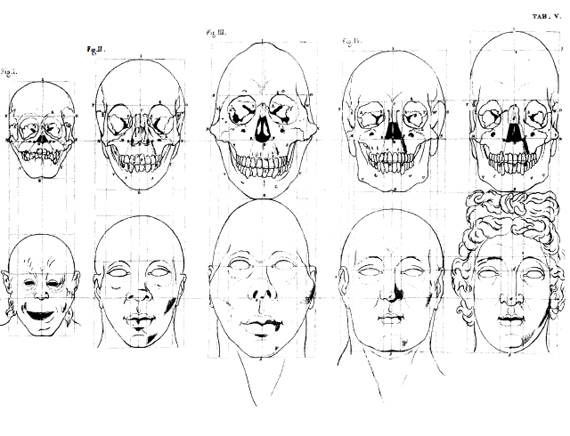

Indeed, aesthetics enables and exemplifies the production of this subject. For though aesthetics has usually been subordinated to logic or ethics because of its dependence on a sensory element, this very hybridity of the aesthetic makes it a privileged point of contact between the supersensible and the sensory worlds, and also grants it inherent pragmatic and pedagogical force. Since its mission is to guarantee and promote spirits articulation with the world, the aesthetic establishes disinterested space in the service of a certain referential effectivity. In the harmonious free play of the faculties which results when Kants subject performs a disinterested aesthetic judgment, the judging subject becomes exemplarycapable, in its formality, of representing universal humanity. Thus in Schillers influential On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795), Kantian themes easily acquire political and historical dimensions. Because aesthetic education is at once the universal history of man and the specific history of the acculturation of certain groups and individuals, aesthetics provides a powerful selfvalidating mechanism for the representativeness of the social groups which can claim to have achieved and inherited this understanding of acculturation. The sheerly empirical qualities of being European, white, middle-class, male, and so on become either tacitly or overtly essentialized as privileged sites in the unfolding of an irreversible aesthetic history. Thus from the sober precincts of philosophy one is led with disconcerting speed to the large reaches of ideology; indeed, ideology then becomes a limit-term difficult to control. For this aesthetic logic of exemplarity subtends powerful Western ideas and discourses of the self, the nation, race, historical process, the literary canon, and the function of criticism; it informs the role of the cultural sphere in modern Western societies, and the mission of the humanities in the modern university. And aesthetics not only structures crucial aspects of mainstream post-Romantic Western culture but also shapes this cultures internal nightmare, as Walter Benjamin indicated in his famous characterization of fascism as the aestheticization of politics. A lurid but necessary task facing any genuine critique of aesthetics is that of engaging both the abyssal difference and the complex proximities between the humanist tradition and what Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy call the Nazi mytha phrase coined to describe not the sociohistorical actuality of German fascism but rather the decisive turns of an ideology that transforms the representative subject of aesthetics into the exemplarity of a master race, and the humanistic, deferred promise of Schillers Aesthetic State into the violent immediacy of a destiny.

Aesthetics thus poses the question of ideology itself in its vacillation between philosophy and politics, and between the languages and practices of high culture and those of modern propaganda. Furthermore, as a process of and discourse about formalization, aesthetics is always also prepared to function as a figure for the act of signification itself. The inflationary aesthetic spiral generates the limit-term of ideology as language. As a philosophical category, aesthetics is the place where the cognitive manifests itself in the phenomenalwhere the essential structure of the sign, in other words, seems to unfold itself as an experience or intuition. Aesthetics translates into psychological or phenomenal terms the unintuitable difference and repetition that allow a linguistic sign to mean and to refer. If Paul de Man asserted that what we call ideology is precisely the confusion of linguistic with natural reality, of reference with phenomenalism, it was because he understood ideology as aesthetics. The full difficulty of such a claim becomes apparent once we realize that it is asking us to conceive of aesthetics as, paradoxically, at once structurally necessary, structurally incoherent, and historically contingenta ghostly event, haunted by its own inauthenticity, yet, despite its impossible and repressed dependence on linguistic difference, possessed of enormous social and political impact.

Next page