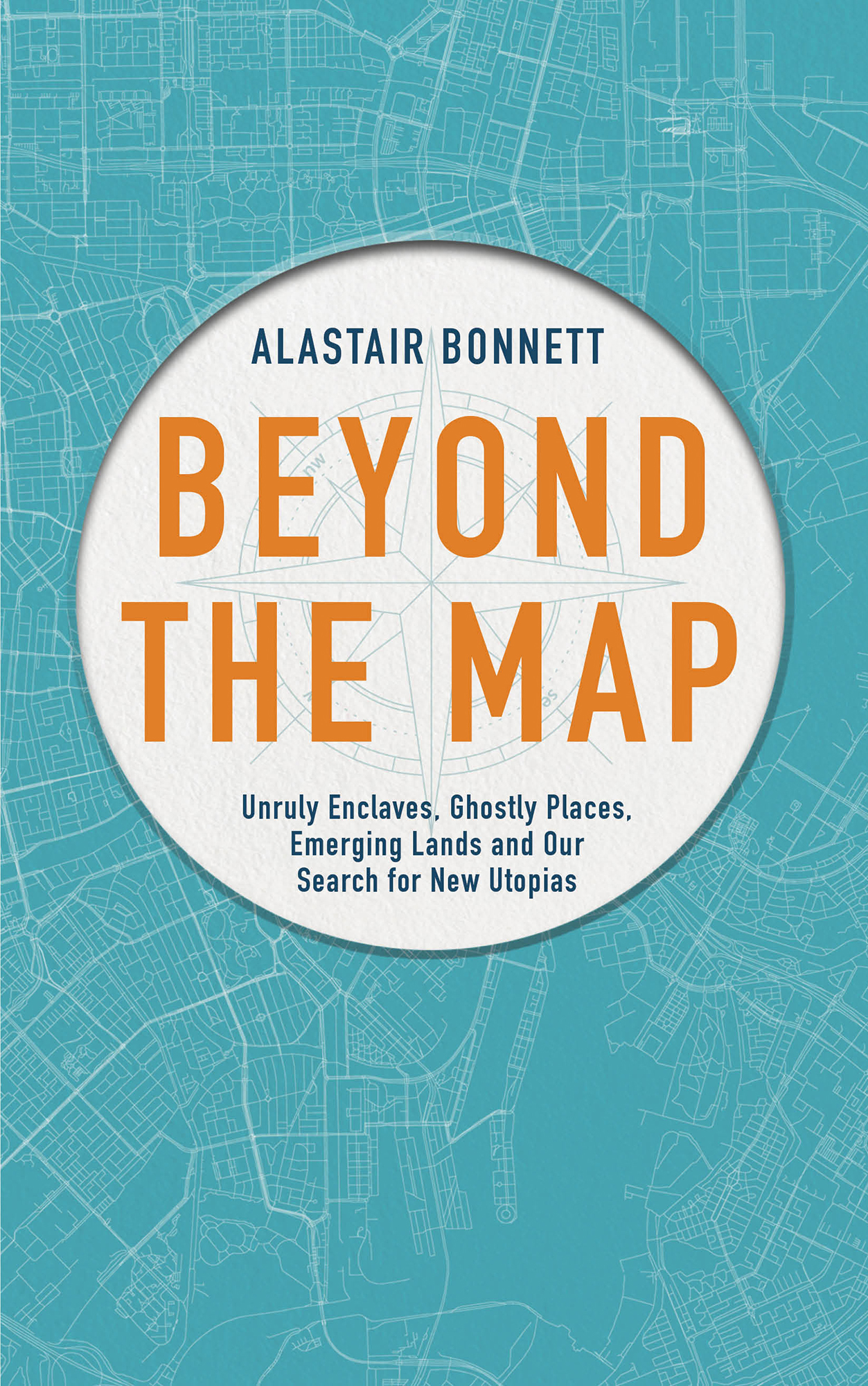

BEYOND THE MAP

Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

ALASTAIR BONNETT

First published in 2017 by Aurum Press

an imprint of The Quarto Group

The Old Brewery, 6 Blundell Street

London N7 9BH

United Kingdom

www.QuartoKnows.com

2017 Quarto Publishing plc.

Text 2017 Alastair Bonnett

Alastair Bonnett has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Aurum Press.

Quotes on from Marshland: Dreams and Nightmares on the Edge of London kindly reproduced with permission from Influx Press. Gareth Rees, 2012, Marshland: Dreams and Nightmares on the Edge of London

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-755-6

Hardcover edition: 978-1-78131-638-2

Illustrations Rachel Holland

Typeset in Minion Pro by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex

Printed and bound by CPI group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Introduction

G eography is getting stranger: new islands are rising up, familiar territories are splintering and secret realms are cracking open their doors. The worlds unruly zones are multiplying and changing fast.

I present thirty-nine stories from thirty-nine extraordinary places, each with something to tell us about the shifting nature of place and place-making. Well be meeting warring enclaves and contemporary utopias, along with many other geographical outliers and pariahs. They are all unique but also connected: the uncanny ruins, the unnatural places, the escape zones and gap spaces, are sites of surprise but also of bewilderment and unease. The compass needle is starting to spin. The adventure before you responds to a new spirit of geographical giddiness. The dizzying fragmentation, the overlapping and shape-shifting of borders that is seen in so many parts of the planet, tell us that geography is not a staid and dusty affair but is enthralling and often alarming.

Ive chosen places whose unique and intriguing stories deserve to be better known and that tell us something about our present state of geographical turbulence. Some, like Trap Streets and the Ferghana Valley, came about as a result of suggestions from readers of my previous books, others from my own out-of-the way travels and research.

We start with unruly islands: disputed, fantastic and legion, they are cresting waves around the world, from the chilly English Channel to the warm seas of the Philippines. Next we explore some old allies of the island: enclaves and new countries. In deep valleys in the Italian Dolomites, and behind a wall that stretches across the Sahara, can be found very different types of survival struggle. These strange and uncertain new territories are brimful with bold ambitions. Its a small leap to our next destination: utopian places. The fraying of traditional geographical borders and loyalties is unleashing utopian energies of every stripe, from the darkest to the most playful. As well as ripping up the map, the radical Islamists of Syria and Iraq are creating a version of utopia, a genocidal exemplar of utopias desire for pure territory. Thankfully there are many other ways of seeking perfection: from beautiful Christiania with its acres of higgledy-piggledy self-build, to the movable pods and capsules of the new nomads, an affluent, self-contained tribe of permanent travellers. Dystopia may get all the cultural hype but in the real world, even around the corner, people are busy trying to build workable alternatives.

Ive been trying to work out why Im so obsessed with place. Its certainly not just because Im a professor of geography. If Im honest, its not a cerebral thing at all. Its to do with the glee and the drama, the love and the loathing the powerful emotions that are poured into place. Thats not enough either: for I am afflicted with an aching nostalgia for lost places, a yearning for the disappeared that guides my thirty-nine steps. In the second half of the book I take you to ghostly and hidden places; from an abandoned British graveyard in India to Garbage City in Cairo; from the hidden zones off Google Street View to the mysteries of the Tokyo metro system; all places that are as unique as they are profoundly disorientating.

I guess Im so drawn to the concealed and the spectral because, like so many of us, Im surrounded by a sense of the fleeting and the impermanent. For as long as I can remember, much of the landscape has looked and felt like a building site. On the long roads I drive, the pathways to work, on each side Im surrounded by streets being gouged up, shovelled away and ever more elaborate traffic systems and flimsy, shed-like buildings being bolted into view. In response, shy hints of the past, leftovers and remnants, take on a totemic power.

Why is that? Ordinary reasons, yet they are mine. Visiting my granny as a small boy, in her chilly house surrounded by overgrown fields, Id wrinkle my nose at the thick scent of coal tar soap, mothballs and door blankets; hear the ticking clock above the snapping coals in the fire. I was swaddled in the past. Wed drive to her remote Suffolk village across sandy heaths, and pass row upon row of neat new terraced homes behind the high wire fences of the adjacent US Air Force base. The serried lines of back garden barbecues, as well as the bases substantial pile of free-fall nuclear bombs, all seemed primed and ready to go. The contrast between the fuggy comfort of grannys home and the prospect of Armageddon, of the winding down, the falling away of village life and the muscular spectacle of world-shaping power, lodged itself in my heart and my geographical imagination.

That was getting on for fifty years ago, but I guess it still helps to explain why Im so drawn to places that have an uneasy mixture of the past and present. Many of the places I explore in this book exhibit a similar layering. Modern places might sometimes feel like leaps into gloriously empty air, but the ghosts wont go away, and Ive come to accept them as necessary, even hopeful, presences. Clambering through the ruins of the Boys Village, which lies in the shadow of a power station in South Wales, a seaside campus for boys from mining communities now collapsing with the weight of weeds and covered in graffiti, I found myself searching out the fireplaces, half-expecting the cosy smell of mothballs, the signs of comfort in an unloved landscape.

A place is a storied landscape, somewhere that has human meaning. But another thing we have started to learn, or relearn, is that places arent just about people; that they reflect our attempt to grasp and make sense of the non-human; the land and its many inhabitants that are forever around and beyond us. It can be an unnerving exchange, especially when what we hope to see is something purely natural, and what we find instead is our own reflection. Shorelines are waxing and waning with increasing speed, and old kingdoms, like Doggerland, as well as new ones in the once-inaccessible Arctic, are being revealed, demanding that we look at the landscape, and at the map, in new ways; as something in motion, unmoored by tradition.