Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

DIRK LIESEMER studied at the Henri-Nannen-Schule in Hamburg and has worked as a newspaper editor in Berlin and Munich. He currently lives in Munich and works as a freelance journalist and author.

Published in 2019 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

4 Cinnamon Row

London SW11 3TW

Copyright 2019 mareverlag, Hamburg

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-912208-32-6

eISBN: 978-1-912208-33-3

Typeset in Compatil Text by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in the Czech Republic by Akcent Media

All rights reserved.

For Andrea

FOREWORD

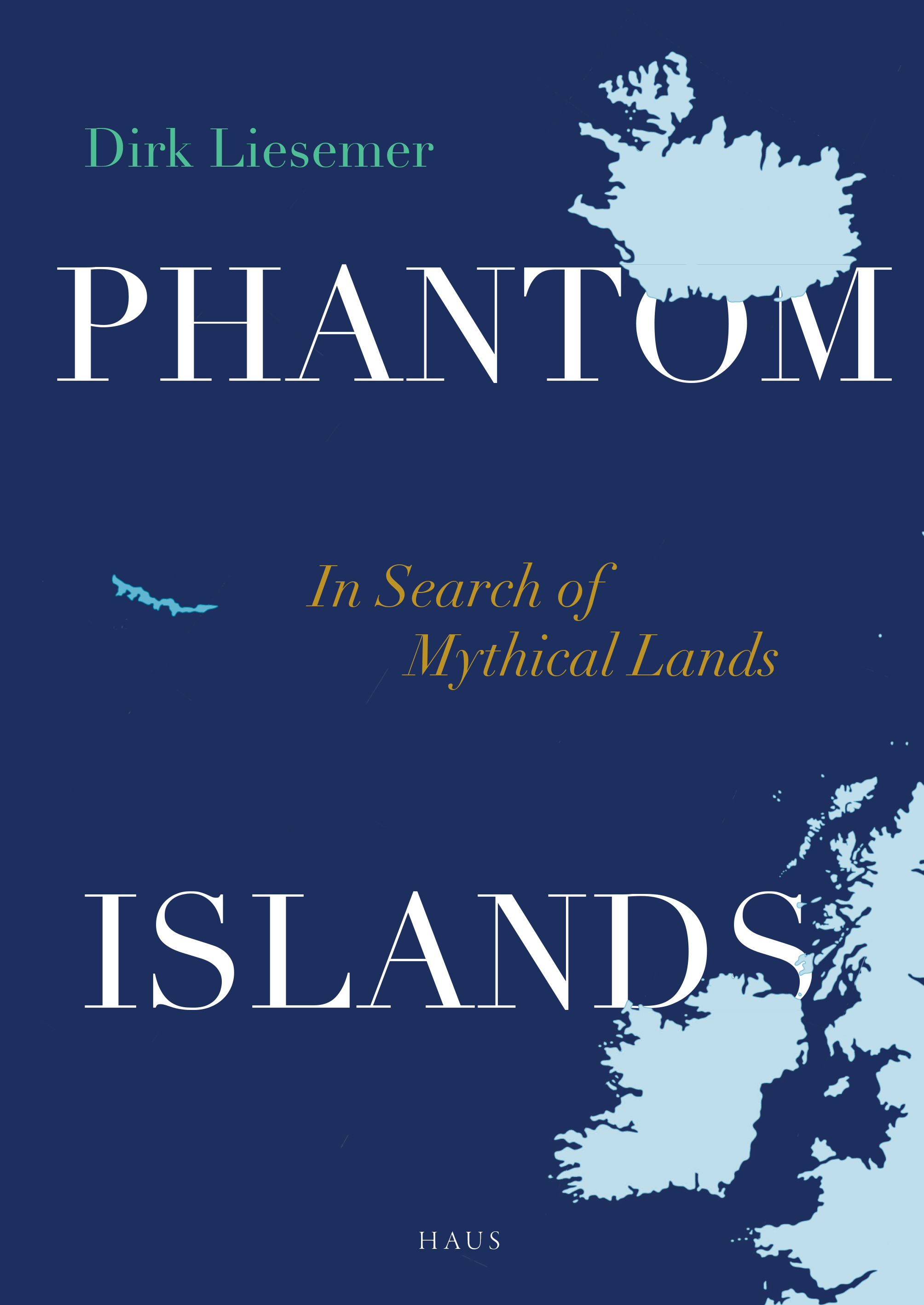

F or many centuries, seafarers, kings, military and naval commanders, pirates and cartographers believed in the existence of islands that were never there in reality. Time and again, expeditions set sail to try to survey them, and more than a few captains reported having actually set foot on Aurora, Breasil, Frisland, Juan de Lisboa, the island of California or the great southern continent of Terra Australis.

The tales of 30 phantom islands contained in this book are 30 journeys across the worlds oceans and back and forth through its history. Every island has its own particular story, yet between the lines, the mindset and the perceptions of the period in which each story first was peddled or gained common currency shine through. For example, it was surely no coincidence that geographers began to postulate the existence of a magnetic island just as the first ships compasses became widespread in Europe. Among the Spanish conquistadors, ideas circulated of a fabled island of gold and a rocky island with sheer cliffs that was home to half-naked Amazons. Devout Christians, meanwhile, dreamt of a Utopia of pious Catholics in the middle of the Atlantic, while at the same time fearing Satanazes, the Devils Island.

More than a few of these phantom islands had their origins in ancient tales or mythical accounts, for instance Thule or Atlantis, the existence of which was seriously posited even in maps of the early modern period. Other islands derived from reports that were passed down through generations by word of mouth; thus it was that the Irish priest Saint Brendan was said to have gone in search of the Isle of the Blessed. His wanderings are recounted in more than 100 different variations. Yet other islands can be traced back to curious logbook entries, shimmering mirages and simple misunderstandings, or even to subtle jokes, downright deception and reprehensible grandstanding. For each case, we can only speculate exactly how the particular ingredients coalesced into a story and how seafarers might have blended their own experiences with hearsay accounts.

The voyages of discovery that were undertaken in the Age of Exploration introduced errors into the early inventories of geographical knowledge on a grand scale. To begin with, the earliest navigational maps (portolan charts) contained little more than lists of ports and dangerous reefs. Many a supposition was founded on quirky theories, such as that of the equilibrium of the Earth. This was used, for instance, to support the theoretical presence of great landmasses in the southern hemisphere or in the Arctic Circle around the North Pole. While a number of phantom islands drifted around early maps like rudderless ships, perpetually on the periphery of the known world, others had their rivers, mountains and cities documented by name.

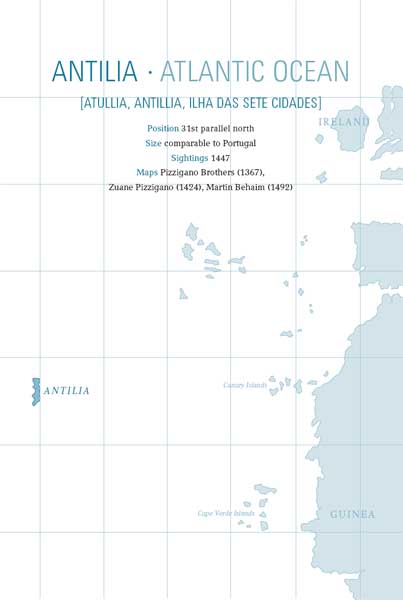

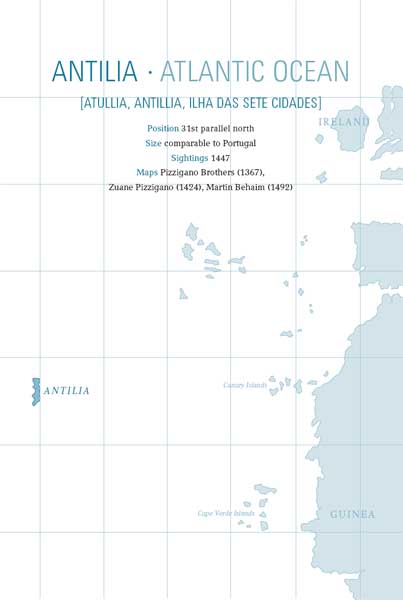

Many islands were places of longing, such as the philosophers island of Kantia as well as Saint Brendans Islands or Antilia. This latter island may well, moreover, have facilitated Christopher Columbuss first voyage westward to the New World. And non-existent islands repeatedly became the focus of squabbles between states; England, for example, declared a good dozen of them sovereign royal territory. As a result of its War of Independence, the United States secured the possession of two supposed islands in Lake Superior. The International Date Line was even once given a kink to the west in order to ensure that the day ended on an American phantom island.

Often, the process of refuting the existence of an island is more exciting, but also more complicated and dangerous, than its discovery. There are quite a few Germans in the ranks of the debunkers of phantom islands, for example the aviation pioneer Hugo Eckener, the zoologist Carl Chun and the polar explorer Wilhelm Filchner, who, at the beginning of the 20th century, even risked his life to prove that an island did not exist.

These 30 stories are not just oddities, however. They can also be read as part of a much larger narrative: we humans are forever trying to gain an overview of the world and yet are prey to the provisional nature of all knowledge. We strive for definitive certainty and, in so doing, barely look beyond the horizon of our own age. We forget all too easily that cartographers had to learn from the ground up to distinguish between myths, opinions and facts; it took a long time before a reliable stock of knowledge could be amassed. The precise image of the world as we know it is only a very recent achievement.

Today, pretty much everywhere has been explored, measured and researched. But even now, old discoveries suddenly wash up again like flotsam. Not long ago, Mexican parliamentarians found themselves arguing over the whereabouts of a supposed island in the Gulf of Mexico. Even more recently, in September 2012, press reports emerged about the futile search for a Pacific island that had found its way onto digital maps of the region.

It may well be that there are still dozens or even hundreds of phantom islands to be found on navigational charts. After all, Indonesia alone is believed to comprise no fewer than 13,677 separate islands, and possibly more than 17,000. Worldwide, there are estimated to be at least 130,000 islands, possibly as many as 180,000 surely a broad enough surface on which to project some new tall tales. One of the latest stories only began on 19 February 2000. A newspaper reported that astronauts aboard the US space shuttle Endeavour had spotted an unknown archipelago in the Andaman Sea, a marginal sea that forms part of the Indian Ocean. A chain of seven islands was clearly visible there, they claimed, arranged in a rough circle off the coast of Thailand. In the centre was an even larger island, like the pupil in the middle of an eyeball; the whole ensemble had supposedly resembled nothing so much as an elephants eye. Who knows? Maybe these islands will make it onto a map before its acknowledged that the astronauts supposed report was a hoax and that these islands are entirely fictitious too.

W ho knows? Had it not been for Antilia, Christopher Columbus might never have ventured as far out over the Atlantic as he did. A long way off in the ocean, so the story went in the 15th century, lay an island by the name of Antilia. Anyone who set sail to try to find a passage to Asia could drop anchor off its shores as a final port of call. There, they could take on board fresh water, fruit, victuals and a whole lot more besides. This island has such an overabundance of precious stones and metals that the temples and royal palaces are covered with plaques of gold, wrote the Florentine astrologer and mathematician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli in a letter of 25 June 1474.

![Greek islands [2018]](/uploads/posts/book/209249/thumbs/greek-islands-2018.jpg)