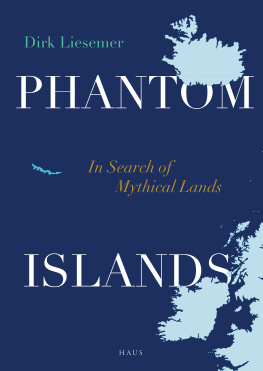

LOST

ISLANDS

THE STORY OF ISLANDS THAT HAVE VANISHED FROM NAUTICAL CHARTS

HENRY STOMMEL

FOREWORD BY

REAR-ADMIRAL G. S. RITCHIE R. N. (RET.)

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2017, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1984 by The University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver. The original foldout map has been reproduced here on single pages in an eighteen-page section at the end of the book.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-78467-0

ISBN-10: 0-486-78467-3

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

784673012017

www.doverpublications.com

Dedicated to the hydrographers

of three centuries who

surveyed the ocean

Contents

Maps

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Of the mariners and scholars who have generously offered advice and information to me during the preparation of this book, I have leaned most heavily upon Lt. Cdr. A.C.F. David of the Hydrographic Department, Taunton, Somerset. His gentle guidance and wide knowledge have contributed greatly to what I have been able to do. The former Hydrographer Rear-Admiral G. S. Ritchie has always been a friend to oceanographers. After his retirement he served as president of the International Hydrographic Bureau at Monaco and kindly provided key information and loaned me some rare books from his own library.

The New York private cartographer Richard Edes Harrison kindled my interest by revealing to me the wonders of the 1922 Bartholomew Atlas, and John C. Bartholomew himself explained to me their history.

Amongst those who have been helpful are H. Derek Howse and Christopher Terrell of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; Helen Wallis of the Map Room of the British Library; H. G. Bilcliffe and F. Herbert of the Royal Geographical Society; H. G. Gierloff-Emden of Munich; Wilhelm Odelberg of the University Library, Stockholm; Gregorio Parrilla of the Instituto Oceanografico, Madrid; Madame Lourdes Diaz-Trechuelo of the University of Cordoba; W. H. Pearson of the University of Auckland, New Zealand; J.S.Turner, P.D. Shaughnessy, and Robert Langdon of Australian National University, Canberra; G. Cresswell and Murray Grieg of the Oceanographic Institute in Tasmania, and Peter Best of the South African Fisheries Laboratory at Roggebai.

In the United States I am indebted for many kindnesses to John Koza and Gregor Trinkaus-Randall of the Peabody Museum, Salem; Irene Norton of the Essex Institute, Salem; Paul Cyr of the New Bedford Public Library; Alden P. Colvocoresses of the U.S. Geological Survey; Judy Ashmore of the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole; Diane Jacob of the Preston Library of the Virginia Military Institute; Patricia Maddocks of the U. S. Naval Institute, Annapolis; Virginia Rust of the Huntington Library, California; John T. Shupe of the National Geographical Society; E. H. Bryan of the Bishop Museum, Honolulu; Dennis Moore of the University of Hawaii; Louis DeVorsey of the University of Georgia; Leslie H. Brown and W. H. Twaddell of the U.S. State Department; John Beasley of Union Theological Seminary, New York City, and Douglas Stein of the Mystic Seaport Museum. For editorial advice I must also add C. Godfrey Day, Tom Suarez, Jim Gilbert, and Capt. Robert Munns.

The two charts are reproduced by permission of the Hydrographer, Taunton; the page from the Book of OBrasil by permission of the Royal Irish Academy; the photograph of the effigy of Admiral Cloudesly Shovell by courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, the photograph of the new volcanic island of Kavachi, by permission of Dr. Jack Dymond of Oregon State University, and the map of the search pattern of the Norvegia, from The Geographical Review, vol 22, 1932, with the permission of the American Geographical Society.

Foreword by Rear-Admiral G. S. Ritchie C.B., D.S.C., R.N. (Ret.)

Hydrography of the Navy (U.K.) 196671

President International Hydrographic Bureau, Monaco 197282

T he thrills of raising a remote ocean island after many days at sea are never to be forgotten. First the crowns of the palm trees appear as black dots beneath a bank of high cumulus on the far horizon; later the silver threads of breakers along the reef-edge sparkle in the sunlight; and while the dazzling white of the beaches and the sombre green of the vegetation assault the eye one becomes aware of the sweet scents of the land frangipani, pandanus and copra as the vessel is directed to the lee side of the atoll in search of a ledge on which to anchor.

The rattle of the anchor cable arouses the islanders who hurry from the cluster of tree-shaded huts and smoking fires to man their canoes and paddle out to inspect their visitors. You have discovered your island.

The discovery of remote islands scattered across the worlds oceans, whether lush and inhabited or bleak and devoid of life except for seals and seabirds, formed a recurring stimulus for European and American explorers, sealers and whalers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, hardly less compelling than the desperate desire of the voyaging Vikings and Polynesians, centuries earlier, to find new homelands.

Henry Stommel is an oceanographer with many years experience at sea who rejoices in the observation of natural phenomena far beyond the confines of any particular study currently engaging him. He is reminiscent of the nineteenth-century oceanographers who were excited by every facet of the new ocean world they were exploring. Here Henry tells the story of how hundreds of islands appeared on and later disappeared from the seamans charts, and how a few survived.

Islands, some true, some false, and others wildly misplaced owing to the difficulties of finding longitude at sea, littered the charts by the latter part of the nineteenth century. Accordingly the British and United States Hydrographic Offices began to make serious efforts to remove the many doubtful islands and to consolidate, with the assistance of mariners, the positions of those deemed to exist. In pursuit of these aims lists of reported dangers were compiled for the several oceans and published for the guidance of navigators. These lists have formed the point of departure for the authors extensive, and often exciting, research.

In this book are to be found tales of how banks of low cloud and icebergs glimpsed from the decks of ships in low visibility blossomed on charts as new discoveries and of how phantom islands were reported by rascals wishing to give credence to their seagoing ventures for which financial backing was required.

The author reports a recent sighting of an island in the Southern Ocean by officers of the Woods Hole research vessel Atlantis II showing how simple it would be to place an island on the map, and how difficult to remove it therefrom even today when satellite surveillance could be expected to have settled the hash of every island of doubtful existence.

As a sea surveyor and chart maker I have found the reading of Henry Stommels stories a delight. I am confident that I shall be joined in this pleasure by seamen, cartographers, hydrographers, romantics, islomanes and indeed all who are interested in the long history of exploring the worlds oceans and exploiting the resources which are found upon many, but by no means all, oceanic islands.

Preface

N ineteenth-century nautical charts and atlases contained some two hundred islands that are now known not to exist. Despite efforts to expunge them, these islands have been tenacious of life and can be found on globes in airline offices, commercial atlases, and official sailing directions. The circumstances of their discovery, confirmation, and later, efforts to expunge them are a byway in the history of geographical exploration that should interest those who love old maps and travel to unusual places.

![Greek islands [2018]](/uploads/posts/book/209249/thumbs/greek-islands-2018.jpg)