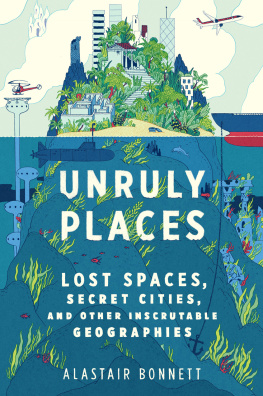

OFF THE MAP

Lost Spaces, Invisible Cities, Forgotten Islands,

Feral Places, and What They Tell Us About the World

Alastair Bonnett

First published in Great Britain

2014 by Aurum Press Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

Islington

London N1 9PF

www.aurumpress.co.uk

This eBook edition first published in 2014

Copyright Alastair Bonnett 2014

Alastair Bonnett has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

Illustrations Lauren Nassef

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eBook conversion by Quarto Publishing Group USA

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-267-4

Softcover edition: 978-1-78131-257-5

For Helen and Paul

Contents

Introduction

O ur fascination with remarkable places is as old as geography. Eratostheness Geographika, written around 200 BC, offers a tour of numerous famous cities and great rivers, while the seventeen volumes of Strabos Geography, written in the first years of the first century AD for Roman imperial administrators, provides an exhaustive compendium of journeys, cities and destinations. My favourite of Strabos places are the gold mines of India which, he tells us, are dug by ants no smaller than foxes that possess pelts like those of leopards. Yet although our appetite for curious tales from afar has been continuous, today our need for geographical re-enchantment is of a different order.

I root my love of place in Epping. Its one of many commuter towns near London, pleasant enough but generic and placeless. Its where I was born and grew up. As I used to rattle out to Epping on the Central Line or drive there along Londons orbital motorway, I often felt as if I were travelling from nowhere to nowhere. Moving through landscapes that once meant something, perhaps an awful lot, but have been reduced to spaces of transit where everything is temporary and everyone is just passing through gave me a sense of unease and a hunger for places that matter.

You dont have to walk far into our coagulated roadscape to realise that, over the past hundred years or so and across the world, we have become much better at destroying places than building them. The titles of a clutch of recent books such as Paul Kingsnorths Real England, Marc Augs Non-Places and James Kunstlers The Geography of Nowhere indicate an emergent anxiety. What is being tapped into by these authors is a widespread feeling that the replacement of unique and distinct places by generic blandscapes is severing us from something important. One of the worlds most eminent thinkers on place, Edward Casey, a professor of philosophy at Stony Brook University, New York, argues that the encroachment of an indifferent sameness-of-place on a global scale is eating away at our sense of self and makes the human subject long for a diversity of places. Casey casts a sceptical eye over the intellectual drift away from thinking about place. In ancient and medieval thought place was often centre stage; the ground and context for everything else. Aristotle thought place should take precedence of all other things because place gives order to the world. Casey tells us that Aristotle claimed that place gives bountiful aegis active protective support to what it locates. But the universalist pretensions of first, monotheistic religion and then the Enlightenment conspired to represent place as parochial, as a prosaic footnote when compared to their grand but abstract visions of global oneness. Most modern intellectuals and scientists have hardly any interest in place for they consider their theories to be applicable everywhere. Place was demoted and displaced, a process that was helped on its way by the rise of its slightly pompous and suitably abstract geographical rival, the idea of space. Space sounds modern in a way place doesnt: it evokes mobility and the absence of restrictions; it promises empty landscapes filled with promise. When confronted with the filled-in busyness and oddity of place the reaction of modern societies has been to straighten and rationalise, to prioritise connections and erase obstacles, to overcome place with space.

In his philosophical history The Fate of Place, Casey charts a growing disdain for the genus loci: indifference to the specialness of place. We all live with the results. Most of us can see them outside the window. In a hyper-mobile world, a love of place can easily be cast as pass, even reactionary. When human fulfilment is measured out in air miles and when even geographers subscribe to the idea, as expressed by Professor William J. Mitchell of MIT, that communities increasingly find their common ground in cyberspace rather than terra firma, wanting to think about place can seem a little perverse. Yet placelessness is neither intellectually nor emotionally satisfying. Sir Thomas Moores Greek neologism utopia may translate as no place but a placeless world is a dystopian prospect.

Place is a protean and fundamental aspect of what it is to be human. We are a place-making and place-loving species. The renowned evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson talks about the innate and biologically necessary human love of living things as biophilia. He suggests that biophilia both connects us together as a species and bonds us to the rest of nature. I would argue that there is an unjustly ignored and equally important geographical equivalent: topophilia, or love of place. The word was coined by the Chinese-American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan about the same time as Wilson introduced biophilia and its pursuit is at the heart of this book.

There is another theme that threads its way throughout the places corralled here the need to escape. This urge is more widespread today than at any point in the past: since fantastic vacation destinations and lifestyles are constantly dangled before us, its no surprise so many feel dissatisfied with their daily routine. The rise of placelessness, on top of the sense that the whole planet is now minutely known and surveilled, has given this dissatisfaction a radical edge, creating an appetite to find places that are off the map and that are somehow secret or at least have the power to surprise us.

When describing the village of Ishmaels native ally and friend, Queequeg, in Moby-Dick, Herman Melville wrote: It is not down in any map; true places never are. Its an odd thing to say but I think it makes immediate, instinctual, sense. It touches on a suspicion that lies just beneath the rational surface of civilisation. When the world has been fully codified and collated, when ambivalences and ambiguities have been so sponged away that we know exactly and objectively where everything is and what it is called, a sense of loss arises. The claim to completeness causes us to mourn the possibility of exploration and muse endlessly on the hope of both novelty and escape. It is within this context that the unnamed and discarded places both far away and those that we pass by every day take on a romantic aura. In a fully discovered world exploration does not stop; it just has to be reinvented.