Reality Media

Reality Media

Jay David Bolter, Maria Engberg, and Blair MacIntyre

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

For David Bolter

For Fredrik Engberg

For Elizabeth Mynatt

Contents

This is a book about augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR). We focus on AR and VR not as technologies, but as part of our complex digital media culture. This perspective has determined what to include and what to omit. Our aim is to show how AR and VR function as media and serve as platforms for existing and new forms of expression, rather than to account fully for their varied history and present usage. We will describe how AR and VR relate to and remediate other, more established media, such as film, television, and games.

The book grew out of our own experience with AR and VR as researchers and teachers. In both those roles, we have necessarily been concerned with the characteristics of AR and VR as technologies. But our main concern has been to explore their affordances and overcome their limitations in order to design effective experiences in the areas of education, storytelling, personal expression, and, more recently, communication and conferencing. In the course of this work, we found ourselves explicitly or implicitly appealing to film, video and television, and screen-based video games, and we became convinced of the value of this comparative approach.

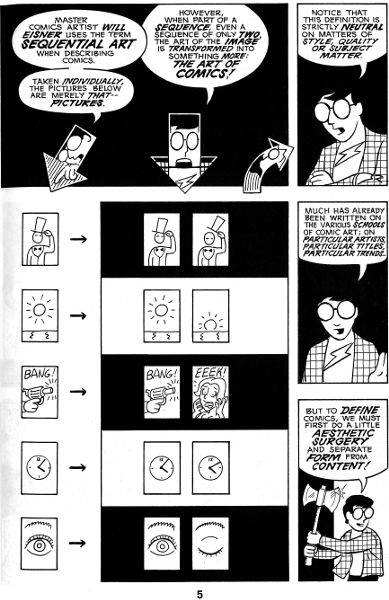

Reflecting on how we could elucidate our approach in a book was what drew us to yet another medium: comics, and specifically the work of Scott McCloud. When the artist and author Scott McCloud analyzed the origin of comics, their nature today, and the future of this popular media form, in Understanding Comics (1993) and Reinventing Comics (2000), he did not produce his analysis as a traditional monograph. He came up instead with the ingenious idea of writing his history and theory of comics in the form of a comic book. He drew himself as a talking character, who deliversballoon by balloona lecture on the subject to which he has devoted his life.

In a conventional book, text and illustrations are separate modes of expression, but in Understanding Comics they are intimately connected. Each panel is both text and illustration. When McCloud wants to define how comics function as sequential art, he actually shows the reader how the panels form sequences to represent the passage of time or cause and effect. McCloud as a character is literally drawn into the argument he is making (figure P.1).

McClouds playful approach inspired us to try to explain a medium in and through the same medium. What McCloud did for comics, we want to try to do for AR and VR. We seek to explain AR and VR in and through AR and VR. But we admit at the outset that we cannot entirely follow McClouds example here. McCloud was able to write an essay on comics in the form of a comic because both prose essays and comics exist in the same medium of ink on paper. In our case, AR and VR cannot function on the printed page; they are born-digital media forms. It is difficult to illustrate AR and VR in the pages of a printed book, and equally difficult to incorporate a lengthy textual discussion in an AR or VR application.

While McCloud could express himself in a single medium, we need two: print and digital, each favoring a different format, a different ratio of text and image, and different ways of engaging the reader or user. The lack of a single unified medium is a limitation, but it allows us to present the media forms from two perspectivesfrom the inside and from the outside. The digital version allows the reader to get inside AR and VRto interact with or even inhabit the media. The printed version is the opposite of an immersive AR and VR experience, contextualizing the technologies that the user experiences in the digital version. It describes the places of AR and VR as media in the history of other media, and it speculates on the future of AR and VR. The printed version is independent of the digital, although the two are in dialogue. A reader will be able to understand the printed book without experiencing the digital version, and vice versa, but your understanding will be enhanced (we hope) if you experience both forms.

There is another major difference between McClouds project and ours. In Understanding Comics, McCloud was presenting a medium with a long and richly varied tradition that he could draw on for evidence. In our case, although they have long been laboratory technologies, AR and VR are just beginning to constitute media with thousands or millions of users. AR and VR are in the process of developing in an ever-changing environment. The American research and advisory firm Gartner issues yearly reports of their so-called hype cycle of emerging technologies. In 2018, they indicated that VR had just moved off the slope of enlightenment, while AR was still in the trough of disillusion and had years to go before reaching maturity (Panetta 2018). As of 2019, Gartner decided that the AR cloud was on the rise, whereas AR and VR were part of technologies that were no longer emerging and would not be included in the hype cycle (Panetta 2019). Gartners hype cycle is only one indicator of the repeated waxing and waning of these technologies during recent decades. But as many application genres and commercially available devices that support AR and VR have emerged, the impact of AR and VR as media forms is becoming increasingly clear.

Figure P.1

In Scott McClouds Understanding Comics, text and illustrations are unified into one form of expression. Reprinted with the permission of HarperPerennial, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art by Scott McCloud. 1993 by Scott McCloud.

Both the printed book and its digital companion are addressed to those who want to understand augmented and virtual reality as media. We consider where AR and VR come from, how they function, and how they have come to take a place among the many media channels and platforms that exist today. This requires some consideration of their technical, as well as historical and cultural, contexts, but neither the printed book nor the digital companion delve deeply into the technologies per se. Those who want to learn how to design and implement AR and VR applications or to seek a thorough treatment of computer graphics (CG), tracking technologies, and computer vision will need to look elsewherefor instance, to the excellent work of Aukstakalnis (2016); Billinghurst, Clark, and Lee (2015); Hughes et al. (2014); Jerald (2016); Pangilinan, Lukas, and Mohan (2019); Parisi (2015); and Schmalstieg and Hllerer (2016). We limit our discussion of technical details to the ones that are the most important for situating AR and VR in the particular media tradition that we are identifying, the tradition of what we are calling reality media. And we strongly believe that both design and technical development can benefit from understanding AR and VR as reality media.

Our own thinking about reality media is informed by numerous scholars and computer scientists and researchers, as well as designers, filmmakers, artists, and programmers. Throughout the writing of this book, which culminated in the spring and summer of the COVID-19 pandemic, we met with and discussed our work with many people, and we cannot acknowledge them all individually. Indeed, all our colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Malm University have contributed to the environment of discussion and inquiry that nourished our work. Among colleagues in computer science, design, digital studies, and other disciplines at our own institutions and elsewhere, we owe particular thanks to Sean White, Jaron Lanier, Steve Feiner, Mark Billinghurst, Diane Hosfelt, Maribeth Gandy, Joshua Fisher, Rebecca Rouse, Nassim Parvin, Carl DiSalvo, Bo Reimer, Susan Kozel, Temi Odumosu, Per Linde, Johannes Karlsson, Sebastian Bengtegrd, Bo Peterson, Brooke Belisle, Paul Roquet, Pepita Hesselberth, Maria Poulaki, Lissa Holloway-Attaway, Lars Bergstrm, and Anders Sundnes Lvlie. Gunnar Liestls pioneering work has inspired us and informed our thinking on augmented reality experience design, especially in the realms of education and cultural heritage. We thank our longtime friend and collaborator Michael Joyce, whose artistic exploration of augmented reality and thoughtful critique of digital media have had a formative influence on the thesis of our book. Scott McCloud inspired us in our attempt to create an uncanny digital double for this book. Others who have played key roles in helping to realize the digital version include Colin Freeman, Joshua Crisp, Gheric Speiginer, Alex LaBarre, and Alex Hill. Our students in the Georgia Tech VIP program (under the direction of Ed Coyle) have helped us test prototypes and refine ideas over the past three years. We thank Carina Strm Hyln and Alex LaBarre for their contributions to the books graphics.

Next page