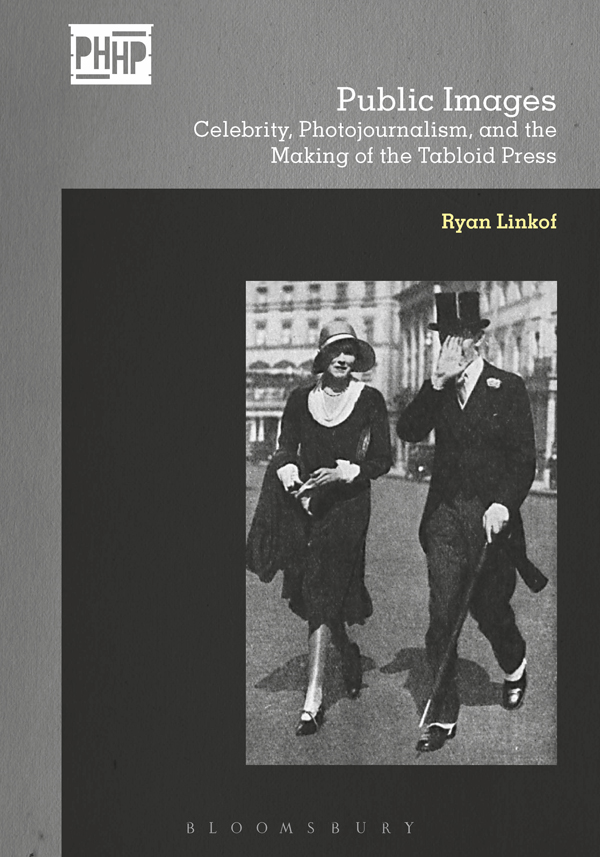

PUBLIC IMAGES

For my mother

PUBLIC IMAGES

Celebrity, Photojournalism, and the Making of the Tabloid Press

Ryan Linkof

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

CONTENTS

In the process of writing this book I have accrued many debts. Researching in three different countries over nearly a decade required the help, guidance, and financial assistance of a number of peopletoo many, in fact, to mention here. This project emerged out of my interactions with colleagues, mentors, and friends, and it has been a collaborative effort in many ways. The unique nature of the intellectual community at the University of Southern California (USC) ensured that my interdisciplinary interests found an engaged and helpful audience. The faculty and students of USCs Visual Studies Graduate Certificate (VSGC) program have been instrumental in helping me to think beyond the parameters of history, and expand my reach into art history, media studies, and cultural theory. This project, it is safe to say, could probably have been written only at USC.

I need to begin by thanking my colleagues at USC who have helped shape this project since its inception. In particular, my advisor Vanessa Schwartz has been an amazing advocate of my work, and an indispensable ally in my professional development. Without her intellectual and moral support, this project would almost surely never have been written. The critical insights of Philippa Levine and Richard Meyer have also shaped the project, and their work has been hugely influential in my own scholarly development. It was an honor to have such a talented and intelligent collection of minds reviewing my work. I also need to thank my two closest confidantes in the dissertation process, Catherine Clark and Brian Jacobson, who offered edits, intellectual guidance, and advice when I most needed it. VSGCs dissertation reading group always served as my first point of call when finishing a draft of my chapter, so I must give a special thanks to Elizabeth Affuso, Jennifer Black, Karen Higa, Chera Kee, Anca Lasc, and Amy Von Lintel, and all of whom helped turn undigested material into the project it has become.

I also need to express my thanks for the financial support that I received during the process of researching this project, both from USC and from a number of grants agencies and institutions. The project would never have been possible without the funds and intellectual support of the Social Science Research Councils Dissertation Proposal Development Fellowship. The mentoring professors and graduate student colleagues of the Visual Culture research group and workshop were an important force in forging this project and providing input during the dissertations gestation. In particular, I must give a special thanks to Emerson Bowyer, who helped to strengthen some of the key ideas of the project. I also received an enormous amount of financial support from the Dana and David Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, through their International Research Fellowship, as well as a number of privately endowed fellowships offered through the college, including the Louis D. Beaumont Fellowship and the Gold Family Endowment Fellowship. The intellectual and financial support of my one-year fellowship at the Center for Law, History and Culture at USCs Gould School of Law played an indispensable role in forging the project. The Roberta Persinger Foulke Endowment Fellowship, offered through USCs Department of History, was also an important source of funding. The financial support of the VSGC, providing funding for summer research for three consecutive summers, allowed me to conduct research in London, New York, and Paris, without which the project would never have been possible. The financial and intellectual support of the Mellon Foundation, through their Seminar in Modern British History at Columbia University, fundamentally affected how I had conceived and implemented the project. The careful edits and engaging discussion of the fellow members of that seminar, and the outstanding guidance and direction provided by Professor Susan Pedersen, helped me to rethink the project at an important stage in its development.

The team at Bloomsbury Publishing has been of tremendous support throughout this process. From the moment I was approached to participate in this series, I have been in the capable hands of Bloomsburys editors. The insights that theyand the peer reviewersprovided throughout this process have helped to shape a dissertation into a scholarly publication.

Finally, I would like to thank all of my friends and colleagues who provided support throughout my tenure as a graduate student, and in the years since I have moved outside the confines of academia and into my career as a museum curator. The support of Britt Salvesen, who encouraged me to continue work on this and other projects while simultaneously working on a number of exhibitions, is deeply appreciated. Her intellectual curiosity and ability to look beyond the art historical canon has been a tremendous inspiration. While I rarely shared drafts of this project with my closest friends, they provided essential support to complete this project, and their intelligence and insights help forge my own critical eye. Even if they were not aware that they were helping me, they often were. In particular, the support (both intellectual and emotional) of Garrett Morgan was an absolutely crucial force in the final stages of this project. So, for that, a very special thank you to him.

The introduction of newspaper photography was a phenomenon of immense importance, one that changed the outlook of the masses. Before the first press pictures, the ordinary man could visualize only those events that took place near him, on his street or in his village. Photography opened a window, as it were. The faces of public personalities became familiar and things that happened all over the world were his to share.

GISLE FREUND

Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.

SUSAN SONTAG

In his scathing 1927 polemic Stentor: or the Press of To-day and To-morrow, critic David Ockham asked, What, actually is a newspaper? In a book dedicated to eviscerating popular news reporting, he gave special attention to the photographic content of newspapers such as the Daily Mirror and the Daily Sketch, Londons most popular tabloids. He wrote,

Then there is a page of pictures, gathered at great expense from the ends of the earth, often transmitted by aeroplane, and providing a feast of new hats and evening wraps from Paris, railway accidents, shipwrecks, upturned tramcars and motor lorries that have fallen into ditches, the more or less recognisable portraits of men and women performing at the Divorce Courts or for some other reason temporarily in the public eye, photographs of film actresses, and pictures of the diversions of the Rich at the races, on the moors, on the Lido, and on the Riviera. Democracys peep-show.

The palpable disdain evident in Ockhams book was shared by many of his contemporaries, and continues to influence perspectives on the tabloid press. The tabloids are at once frivolous and somehow insidioussimultaneously eroding the informational content of the news and providing too much information. Following the rich and famous to the ends of the earth, tabloid photographers seem never to rest in their pursuit of mindless, and morally dubious, photographic spying. These photographers transacted a voyeuristic expedition on behalf of the mass public, looking through the keyhole with camera in hand, in the service of Democracys peep show.