A Failure of Capitalism

Copyrighted image removed by Publisher

Preface

The world's banking system collapsed last fall, was placed on life support at a cost of some trillions of dollars, and remains comatose. We may be too close to the event to grasp its enormity. A vocabulary rich only in euphemisms calls what has happened to the economy a "recession." We are well beyond that. We are in the midst of the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. It began as a recession that is true in December 2007, though it was not so gentle a downturn that it should have taken almost a year for economists to agree that a recession had begun then. (Economists have become a lagging indicator of our economic troubles.) The recession had been triggered by a sharp nationwide drop in housing prices the previous summer that had caused the market in "subprime"very riskymortgage loans to collapse. Housing prices had been bid up to unsustainable heights in the early 2000s. When the market decided that houses were no longer such a super investment, many people who were overmortgaged relative to the value of their houses defaulted, and either abandoned their house or were forced out by foreclosure. The result was a glut of unsold houses and a drastic reduction in the amount of home building, as well as a great many nonperforming mortgages. Two mortgage hedge funds owned by the investment bank Bear Stearns went broke in the summer of 2007, along with American Home Mortgage Corporation and three investment funds owned by the French bank BNP Paribas. Countrywide Financial Corporation, the nation's largest mortgage lender, narrowly averted bankruptcy.

The recession was overtaken by a financial crisis in March 2008, when Bear Stearns itself collapsed. The crisis became acute in mid-September, when the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the distress sale of Merrill Lynch, the near collapse and ensuing government takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (giant buyers and insurers of residential mortgages), and the bailout of American International Group, the nation's largest insurance company, triggered a sharp drop in the stock mar ket and a worldwide credit freeze. Frantic efforts by the Federal Reserve, the Treasury Department, and Congress to save the financial system ensued. These efforts culminated in early October when Congress enacted a $700 billion bailout of the banking industry (TARP the Troubled Asset Relief Program). But the bailout could not prevent the further deepening of the recession. By the end of 2008 with the Detroit automakers on the verge of bankruptcy and economic activity everywhere declining sharply, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average having declined to 8,800 (at this writing February 2, 2009 it is down to 7,900) from 14,000 in October 2007 and from 11,100 as recently as September 26, and with the Federal Reserve making desperate efforts to prevent a deflation the recession was beginning to be seen as the first U.S. depression since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The word itself is taboo in respectable circles, reflecting a kind of magical thinking: if we don't call the economic crisis a "depression," it can't be one. But no one who has lived through the modest downturns in the American economy of recent decades could think them comparable to the present situation. The actions that the government has taken and plans to take bespeak fear that without radical measures of the kind that were or perhaps should have been taken during the Great Depression, we could find ourselves in almost as dire a predicament. It is the gravity of the economic downturn, the radicalism of the government's responses, and the pervading sense of crisis that mark what the economy is going through as a depression.

There is no widely agreed definition of the word, but I would define it as a steep reduction in output that causes or threatens to cause deflation and creates widespread public anxiety and, among the political and economic elites, a sense of crisis that evokes extremely costly efforts at remediation. It is too early to tell how protracted the downturn will be, and I recognize that protraction, so notable a feature of the Great Depression (especially in the United States), is a common marker for depressions. But it is expected to exceed in length every recession of the last half-century.

Not that we are likely to see a 34 percent drop in output or an unemployment rate of 24 percent, as in the depth of the Great Depression. But there is semantic space between a "Great Depression" and a mere recession, especially if, as may well happen in the present instance, a "successful" effort to avoid a repetition of the Great Depression will impose enormous long-term costs on the economy. The cost of a depression is not just the loss of output and employment before recovery begins; it is also the cost of the recovery, including such aftershock costs as inflation; there may be political costs as well.

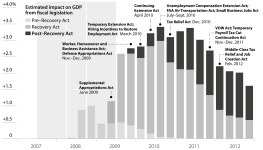

At this writing, the federal government, in a desperate effort to speed the recovery, has spent or committed to spend (I include the stimulus package now wending its way through Congress, as it seems certain to be enacted) $7.2 trillion ($5.2 trillion by the Federal Reserve, $2 trillion by the Treasury Department), and has guaranteed another $2 trillion in loans and deposits. We are facing the certainty of a huge increase in the national debt and the possibility of a future inflation rate so high that, as in the early 1980s, the Federal Reserve will have to engineer a severe recession (by effecting a sudden sharp increase in interest rates) in order to restore price stability. Such a recession would be an aftershock, and hence a cost, of the present crisis. The aftershock would be all the greater if at the same time that interest rates were rising the government was raising taxes in order to trim an astronomical national debt. And suppose that to reduce the pain of a post-depression recession the Federal Reserve restarted the boom-and-bust cycle by forcing down interest rates. In short, even if the current downturn is arrested within months, the extraordinary measures that the government is taking to arrest it will cause profound economic problems for years.

Some conservatives believe that the depression is the result of unwise government policies. I believe it is a market failure. The government's myopia, passivity, and blunders played a critical role in allowing the recession to balloon into a depression, and so have several fortuitous factors. But without any government regulation of the financial industry, the economy would still, in all likelihood, be in a depression. We are learning from it that we need a more active and intelligent government to keep our model of a capitalist economy from running off the rails. The movement to deregulate the financial industry went too far by exaggerating the resilience the self-healing powers of laissezfaire capitalism.

To understand the economic crisis and draw the appropriate lessons while it is still unfolding will require our close attention to the following questions: What is this depression exactlya mere li quidity crisis? a solvency crisis? something else? and what precipitated it? What are the underlying causes? Why was it not anticipated? How well is the government responding to it? Is the depression unalloyed grief, or may it have some redemptive political or economic consequences the silver lining that every self-respecting cloud should have? What can we learn from it about capitalism, government, and the economics profession? What can be done to head off future depressions? What individuals or institutions are most culpable for having failed to foresee and avert the depression? What is its principal political lesson? I organize my discussion around these questions.