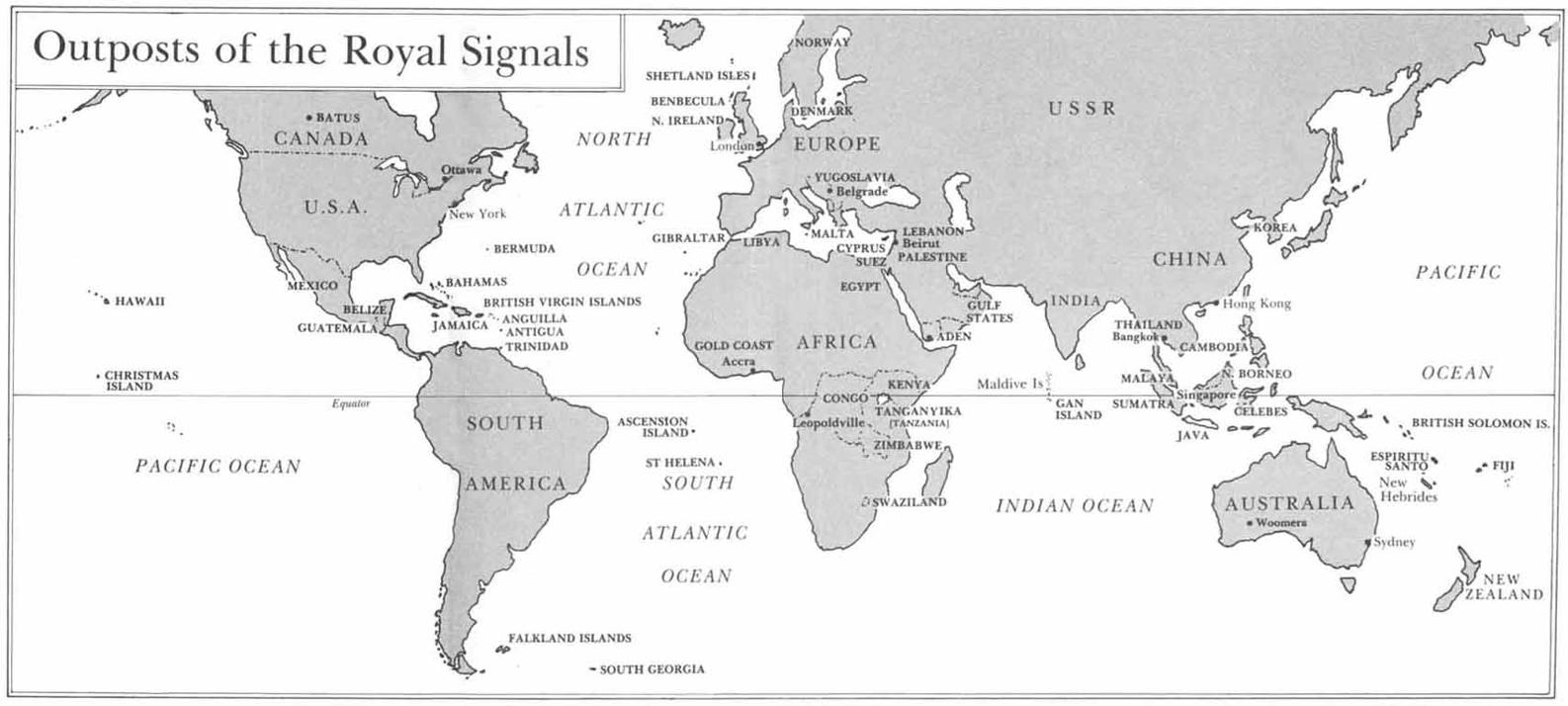

So many members of the Corps have helped me in the production of this book that it would be impossible to list them all. However, there are some of whom mention must be made. Major-General E. J. Hellier formally requested me to write the history, and the members of the Historical Management Committee, chaired first by Brigadier A. M. Willcox, then by Brigadier J. H. Almonds and finally by Brigadier A. H. Boyle, gave me invaluable assistance. I therefore take this opportunity of thanking Major-General D. R. Horsfield, a veteran of the campaign in Burma during the Second World War, who supplied large quantities of essential information, Colonel A. Pagan, Colonel J. Francis, Colonel A. de Bretton Gordon, Lieutenant-Colonel J. Beale and Major A. G. Harfield. Lieutenant-Colonel Robin Painter, another Burma veteran, who was both a member of the Committee and the Corps History Researcher, provided the assistance without which this book simply would not have been possible: nothing was ever too much trouble for him, his advice was invaluable, and his industry was prodigious.

Major-General A. Yeoman arranged an extremely valuable visit to the units in BAOR and provided me with an efficient ADC in Lieutenant M. Fenton. On my tour through 4 Signal Group, 16 Signal Regiment, 21 Signal Regiment, 28 Signal Regiment (which made me an honorary member), 7 Signal Regiment and 14 Signal Regiment I had the fullest help and co-operation from all ranks.

As it would be impracticable to try to thank everyone individually who has helped me to produce this book, I can only thank them generally, which I do, with gratitude.

Western Desert

If the enemy was far off and there was no need for camouflage, a tarpaulin stretched between two cars gave good shade, and so you lay for the midday heat, not sweating for sweat dried as it reached the skin surface, dozing or talking of the unfailing summer noontime topic drink. Only the wireless operator had to stir himself, listening in case Group Headquarters had a message.

And at night, when the rest of the patrol were (more or less) comfortably in bed, sharing with the tired wireless operator the light of a hooded inspection lamp.

Most men in the Long Range Desert Group were specialists in something, and of all these experts the signalman was probably the most important, though the navigators ran them close. For what was primarily a reconnaissance unit good signals were essential. Without them a patrol, three or four hundred miles away from its base, could neither send back vital information nor receive fresh orders. If signals failed, the best thing to do was to come home.

And looking back now I realize how seldom they did fail. We cursed them for having to halt at given times to come up for Group HQ; we disliked their poles and aerials which might advertise to the enemy the presence of a patrol, we scoffed at their atmospherics, skip distances and interferences; we blamed them when they could not get through and when ciphers would not come out; we were impatient with their checks and repeats, forgetting the regularity with which they kept communication.

Long Range Desert Group, W. B. Kennedy-Shaw

Burma

For the signallers there is no peace. They have time only to rid themselves of their equipment before they unload their mules and start erecting their sets. The aerials are slung over the neighbouring trees, sometimes missing their mark and landing with a thud beside a recumbent soldier. In a moment everything is fixed and an operator sits at each set with the sweat of the march still on him. They have a hard time and they deserve the thanks and praise of us all. They have no time to relax or even enjoy the advantage of sitting by a fire watching the food cook or the water boil. Briggs goes round the sets and checks up on progress, repeating the same three words which were to be our theme in the future: Are you through? Jack Masters comes up to Briggs and asks, Are we through? The Brigadier turns to Jack Masters, Are they through? And the only man who can do anything about it is a signalman (the lowest rank in the Royal Signals) on whose ability depends the maintenance of the whole column. So that, while majors swear and brigadiers fume, the man on the set carries quietly on with his job, perhaps a little amused but always conscious of the vital nature of his work.