Mixed Signals

MIXED SIGNALS

HOW INCENTIVES REALLY WORK

URI GNEEZY

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven and London

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2023 by Uri Gneezy.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Adobe Garamond type by Newgen North America.

Printed in Great Britain.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022939728 ISBN 978-0-300-25553-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my sisters Orit and Arza, with love

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Do as I Say, Not as I Do

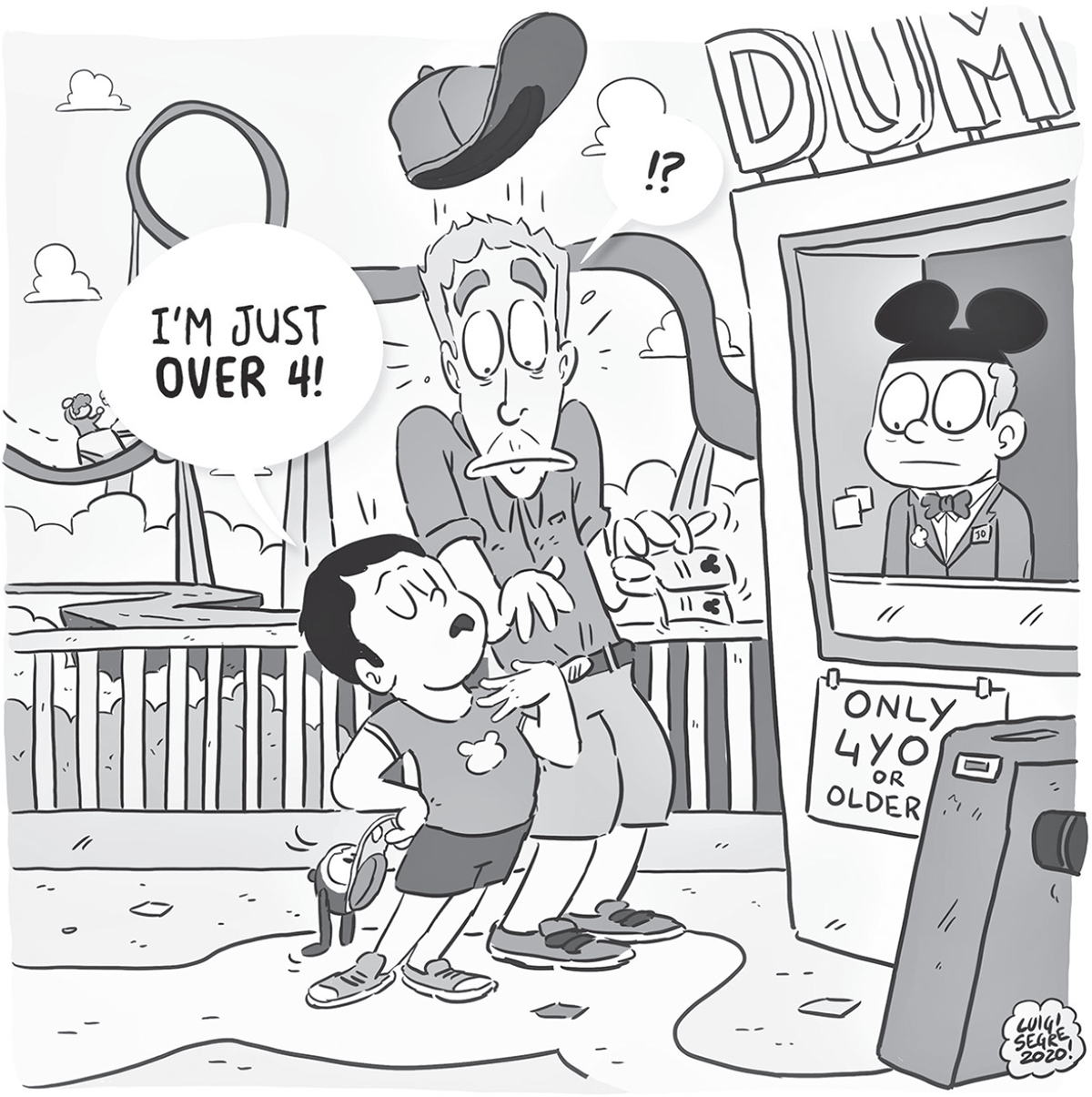

I loved it when my son Ron reached the age when he started effectively communicating with us. Like other kids, he also started to experiment with lying. We told him he shouldnt liebeing honest is what separates the good guys from the bad guys. This moral lesson soon got me into trouble.

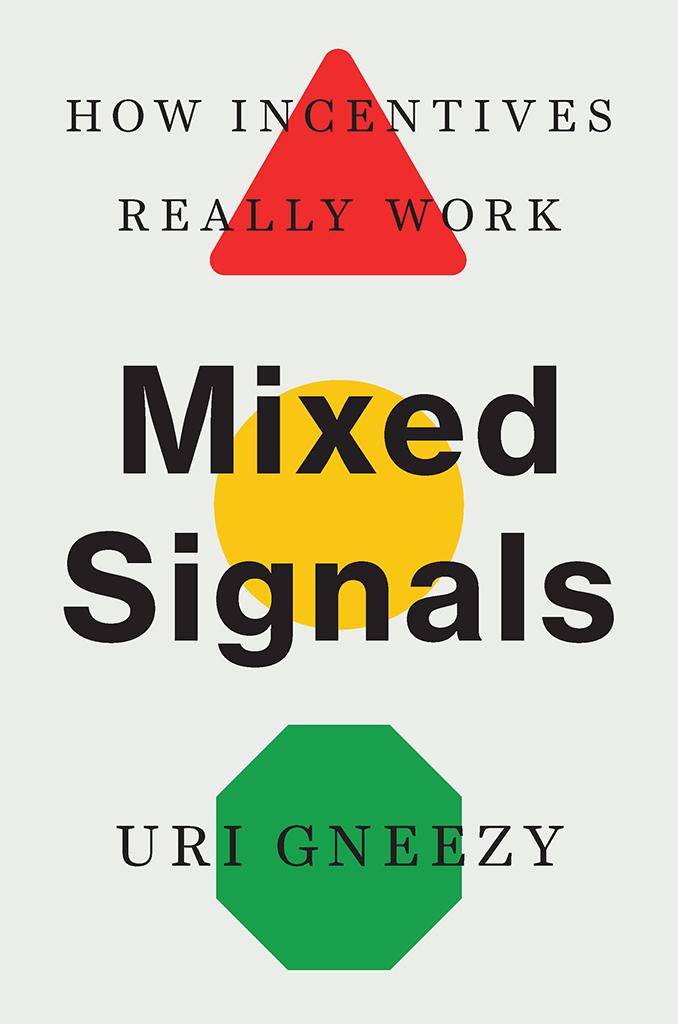

All was good until I took him to Disney World on a nice day in July. We waited in line to purchase tickets, and I saw the sign that said, Under three years old: Free. Three and older: $117. When it was our time to pay, the smiling cashier asked me how old Ron was, and I replied, Almost three. Technically I wasnt lying: he was almost three, but from the wrong side; his third birthday was a couple of months earlier. I paid for myself while the cashier kept smiling, and we went in to have fun.

What happened at the ticket booth and about half an hour later is shown on the next page.

When Ron said, Daddy, Im confused. You told me only bad guys lie, and you just did! I tried the do as I say, not as I do approach, but I dont think it worked.

Before you judge my moral standards, it turns out that Im not the only one who rounds down the age of their kids. An article on Vacationkids.com titled Do You Lie about Your Kids to Get Family Vacation Deals? reports that this question had been searched over two billion times (with a b) on Google! According to Google, Im not alone.

Ron received two contradicting signals from me: what I said versus what I did in the face of a $117 incentive. In a nutshell, this book is about how to avoid such mixed signals: you say one thing, but when the incentives present themselves, you do something else.

Do as I say, not as I do.

What should Ron conclude regarding what I care about? What is the message that Ron heard? What happened when we approached the next ride is shown on the facing page.

The key is to understand that incentives send signals. Too often theres a conflict between what you say and what your incentives signal. You can tell everyone that you care about honesty; talk is cheap. For the claim to be credible, you need to back it up by taking actions that are costly to you, such as paying the full entrance fee. If youll align what you say with the incentives you offer, the signal will be credible and easy to understand.

When you understand signals, you learn how to make incentives more effective. For example, what could Disney do to reduce the number of people lying about age? A simple option is to make people bring documentation, such as a birth certificate, to prove the age of their kids. Thats probably a bad idea because you go to Disney World to be part of a big happy family, not to be policed. While requiring documentation would probably reduce the number of people lying, it would also create a lot of hassle and negative emotions.

Rons takeaway was do as I do, not as I say.

Take a minute to think about a solution.

Heres a solution that is based on signals: Disney could ask that the child be present when you buy the ticket. This would force you to face a mixed-signal dilemma like I did: Am I going to lie in front of my kid or pay $117? Disney can even take it a step further and ask the child to tell their own age, for example, by answering the question, Did you already have your third birthday? You can clearly coach your child to lie to the cashier, but boy, that is one strong and costly signal that lying is acceptable.

Mixed Signals at Work

There are many examples of incentives that send a confusing mixed signal, resulting in a different outcome than intended. As you will see in the pages ahead, even big companies often make such mistakes when designing their incentives.

Imagine a CEO who tells her employees how important it is to work as a team, but the incentives she designs for success are based on an individuals work. The result is simple: the employees would ignore what the CEO says and try to maximize their individual success and monetary gain, as they understand it from the incentives. You may conclude that to avoid such mixed signals, CEOs shouldnt use incentives at all. This book examines both perspectives and explores the middle ground that optimally shapes the incentives so that they are aligned with the intended messages and avoid mixed signals.

Examples of such mixed signals include the following:

Encouraging teamwork but incentivizing individual success

Encouraging long-term goals but incentivizing short-term success

Inspiring innovation and risk-taking but punishing failure

Emphasizing the importance of quality but paying for quantity

My goal is to show you how to be incentive smarthow to avoid these mixed signals and design incentives that are simple, effective, and ethical.

Controlling the Story

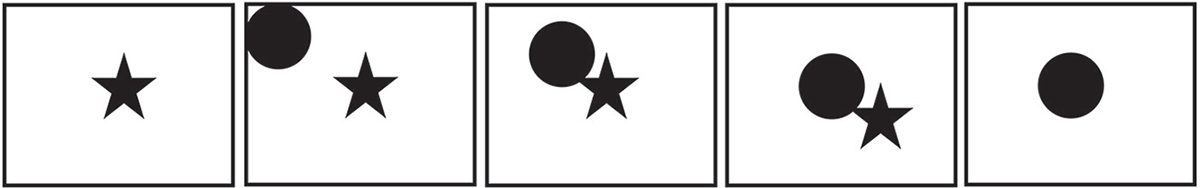

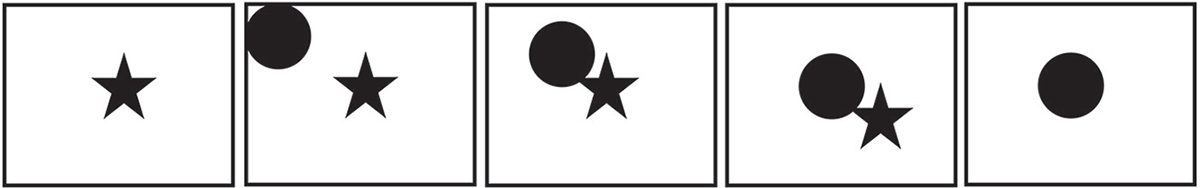

Look at the series of pictures in the figure from left to right. What do you see?

When I ask a lecture audience this question, I hear some very creative and interesting answers. Some are literal, such as A circle appears from the top left and moves toward the center, and the star moves out of the frame. Other replies are more creative: How mediocrity wins over talent; Its better to be a moon than a star; Only the strong survive; or The ball is being rejected.

Whats your story?

The audience injects meaning into the abstract shapes to make sense of them. After having fun with the answers to the first question, I ask the audience to guess what happens next. Again, people have no problem filling in the gaps: Dont worry, the star will come back to claim the center; We learn to live in an unfair world; or The circle is punished.

The psychology behind these reactions is interesting. Our brain tends to fill the gaps between pictures by creating a story out of what we see; instead of simple pictures of objects, our brain creates a narrative and even moral values such as fairness and punishment. Stories help us understand our experience by attaching meaning to complicated events that affect our lives. Stories have many uses: they help us memorize events, evaluate them, and make sense of the world.