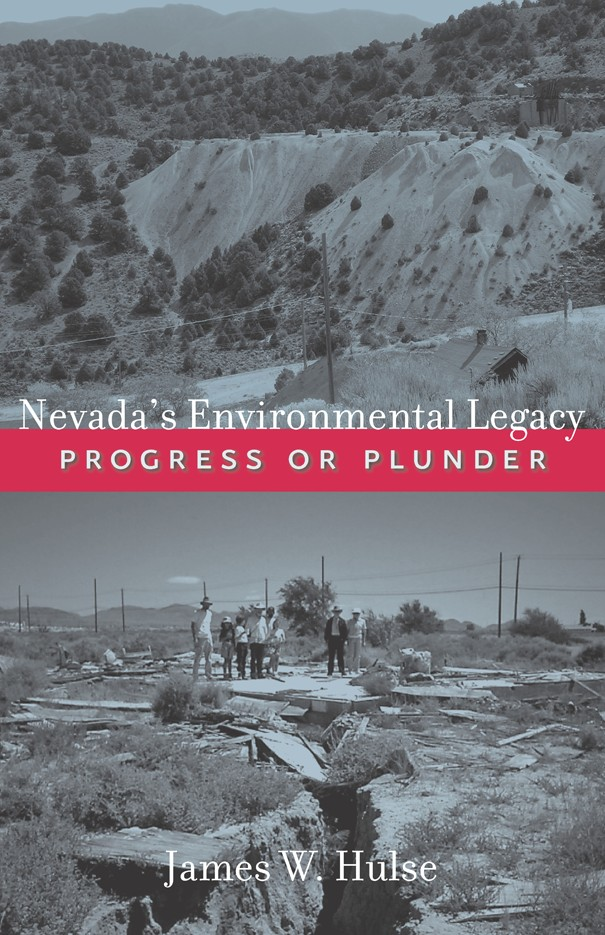

Wilbur S. Shepperson Series in Nevada History

PREFACE

Have we citizens of Nevada been snoozing while the exploiters and profiteers have been taking over our homestead? This is a crude rhetorical question about what has been happening to Nevada in the recent past. It invites more serious public debate on environmental issues.

In this book I offer an assessment of Nevadas environmental experience over the past 150 years. Within the lifetime of some of our senior citizens, we have witnessed profound changes in the natural environment of the state and in our attitudes toward these changes. We have witnessed urban sprawl, a revolution in mining and smelting techniques, transformations of the rangelands, an expanded military presence, development of the Atomic Test Site, the M-X fiasco, a presidential decision to place a national nuclear waste depository in Nevada, and a proposal to make a massive water transfer from rural eastern Nevada to the Las Vegas Valleyamong other challenging events. My intention is to discuss these developments within the broader perspective of Nevada history.

One of the most daunting problems facing our contemporary world, including Nevada, is the pollution and degradation of the environment. So far, historians writing on Nevada have said too little on this subject, and we have made little use of the most obvious evidence before us. I offer this document as a corrective, especially to my own writings but also to others. This book has few answers to the many questions about Nevadas environment that have arisen in recent decades, but my hope is that it will promote further serious inquiry and deeper investigation into the pressing issues.

Environmental concerns have been on the margins of books about Nevada from the beginning of the states history. Most early writings focused on extracting wealth from the earth, improving the land, and building profitable businesses on a challenging terrain. But some of these texts gave little attention to the long-term environmental consequences of all this activity.

Subsequent writings have presented Nevada as a tourist-tempting destination, a relic of the romantic Old West, or a colorful setting in which people can escape their mundane lives within a neon-lit casino. But again, most general studies of Nevadas culture and commerce have left environmental questions on the periphery, like extras or a chorus on the fringes of the stage. This book tries to give these questions a higher billing.

Recently, there have been some scholarly studies and popular writings about the one aspect of Nevadas environmental realities that seems to concern a wide audience. However, most discussions about the Nevada Test Site and military training and testing activities are fairly limited and not especially enlightening.

A small but crucial body of writing has been produced by protestors, using their prophetic voices to sound the alarums for protection of Nevadas fragile natural heritage. Nevada has benefited from private groups like the Sierra Club, Citizen Alert, Great Basin Mine Watch, and the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada (PLAN). These organizations have been the conscience of Nevada on environmental matters for many years. I have tried to draw upon this workwhich represents a fairly slender body of writing and effective activismand to glean from it wherever possible important information about threats to Nevadas environmental well-being.

Late in 2004, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that Nevada led the nation in the percentage of population increase for the eighteenth consecutive year. Most of this growth happened in the Las Vegas Valley, and some of it also along the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada around Reno and Carson City. The southern triangle around Las Vegas is a laboratory where population explosion, a consumption-oriented economy, and ongoing technological revolution are merging in a puzzling triangulation. Whether the problems created by this situation are soluble, and if so, how they are to be solved, are matters of vital national concern as the countrys population continues to grow and continues to shift into the arid, environmentally fragile West.

The rest of the state90 percent of its territoryhas endured less population pressure than the swelling urban centers, but the environmental problems arising there from other causes are among the most profound and most worrisome in the nation. The impacts of overgrazing, massive mining operations, military testing, and water transfer to urban centers may, if not addressed, prove catastrophic.

This book is a chronicle about attracting, tempting, and seducing Nevadans, not only by those who came to exploit, make money, and explode their arsenal on this turf, but also by those who have loved the state. The text that follows is about the uses and abuses of Nevadas land, water, and air, and about the efforts of those who have tried to build the commonwealth and mitigate the damage created by their own efforts or those of their predecessors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My intellectual debts as a historian grow larger every year. Nevada scholars and friends whom I have often acknowledged in the past are high on my list. The scholarly legacies of Russell Elliott and Wilbur Shepperson still provide useful dividends. More recent historians, especially William Rowley of the University of Nevada, Reno; Eugene Moehring and the late Hal Rothman of the University of Nevada Las Vegas; and Michael Green of the College of Southern Nevada have all offered new investments to the fund of insights. The works of Scott Slovic and Cheryll Glotfelty of the University of Nevada, Reno, English Department have also been invaluable.

Once again, librarians and archivists across the state have made this task easier. In their league also are the public information officers of the government and private agencies. Among these are Cindy Peterson, formerly of the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection; Franklin Pemberton and Ed Monnig of the U.S. Forest Service; and Jo Simpson. James Taranik, director of UNRs Mackay School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, was generous as usual with his time and assistance. My quest was empowered by the kindness of Vanya Scott of the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas. Kathy War of the UNLV Librarys Special Collections Department has repeatedly responded to my search for information. Glenn Miller, the senior expert of the Nevada environmental movement, read this manuscript at an early stage and was most helpful. Tina Nappe and Bob Fulkerson read it at a later stage and gave indispensable advice. Robert Loux and Joseph Strolin of the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects have been extremely helpful. And I thank Elizabeth Dilly of The Nature Conservancy, who played an important role in improving this text and its photographs. Its gaps or lapses belong to me.