FUGITIVE TESTIMONY

FUGITIVE TESTIMONY

On the Visual Logic of Slave Narratives

JANET NEARY

Fordham University Press

NEW YORK 2017

Fordham University Press gratefully acknowledges financial assistance provided for the publication of this book from the Offices of the Provost and the Dean of Arts & Sciences, Hunter College, City University of New York.

Copyright 2017 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Neary, Janet, author.

Title: Fugitive testimony : on the visual logic of slave narratives / Janet Neary.

Other titles: On the visual logic of slave narratives

Description: New York : Fordham University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016014311 | ISBN 9780823272891 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780823272907 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Slave narrativesUnited StatesHistory and criticism. | Slavery in art. | Semiotics and the arts. | Art, Modern20th centuryThemes, motives.

Classification: LCC E444 .N43 2017 | DDC 306.3/62092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016014311

Printed in the United States of America

19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

To

Lindon Barrett

and my family

CONTENTS

The distance from Tuckahoe to Wye riverwhere my old master livedwas full twelve miles, and the walk was quite a severe test of my young legs. The journey would have proved too severe for me, but that my dear old grandmotherblessing on her memory!afforded occasional relief by toting me (as Marylanders have it) on her shoulder.... She would have toted me farther, but that I felt myself too much of a man to allow it, and insisted on walking. Releasing dear grandmamma from carrying me, did not make me altogether independent of her, when we happened to pass through portions of the somber woods which lay between Tuckahoe and Wye river. She often found me increasing the energy of my grip, and holding her clothing, lest something should come out of the woods and eat me up. Several old logs and stumps imposed upon me, and got themselves temporarily taken for wild beasts. I could see their legs, eyes, and ears, or I could see something like eyes, legs, and ears, till I got close enough to them to see that the eyes were knots, washed white with rain, and the legs were broken limbs, and the ears, only ears owing to the point from which they were seen. Thus early on I learned that the point from which a thing is viewed is of some importance.

Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom

[Future] literary history will engage in radical strategies to hear the silence of the narratives. It will attend to the gaps, the elisions, the contradictions, and especially the violations. It will turn original purposes on an angle, transform objects into subjects, and abolish the abolitionists. The slave narrators were feeling their way through strange fields in the dark, Arna Bontemps once wrote. When they found light or a break in the fences, they ran on. Abolitionist narratives, for one large instance, are critiques of certain aspects of America. A subgroup of those, in turn, are critiques of critiques.

JOHN SEKORA, BLACK MESSAGE/WHITE ENVELOPE: GENRE, AUTHENTICITY, AND AUTHORITY IN THE ANTEBELLUM SLAVE NARRATIVE

Each now is the now of a particular recognizability. In it, truth is charged to the bursting point with time.... It is not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past: rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation.

WALTER BENJAMIN, THE ARCADES PROJECT

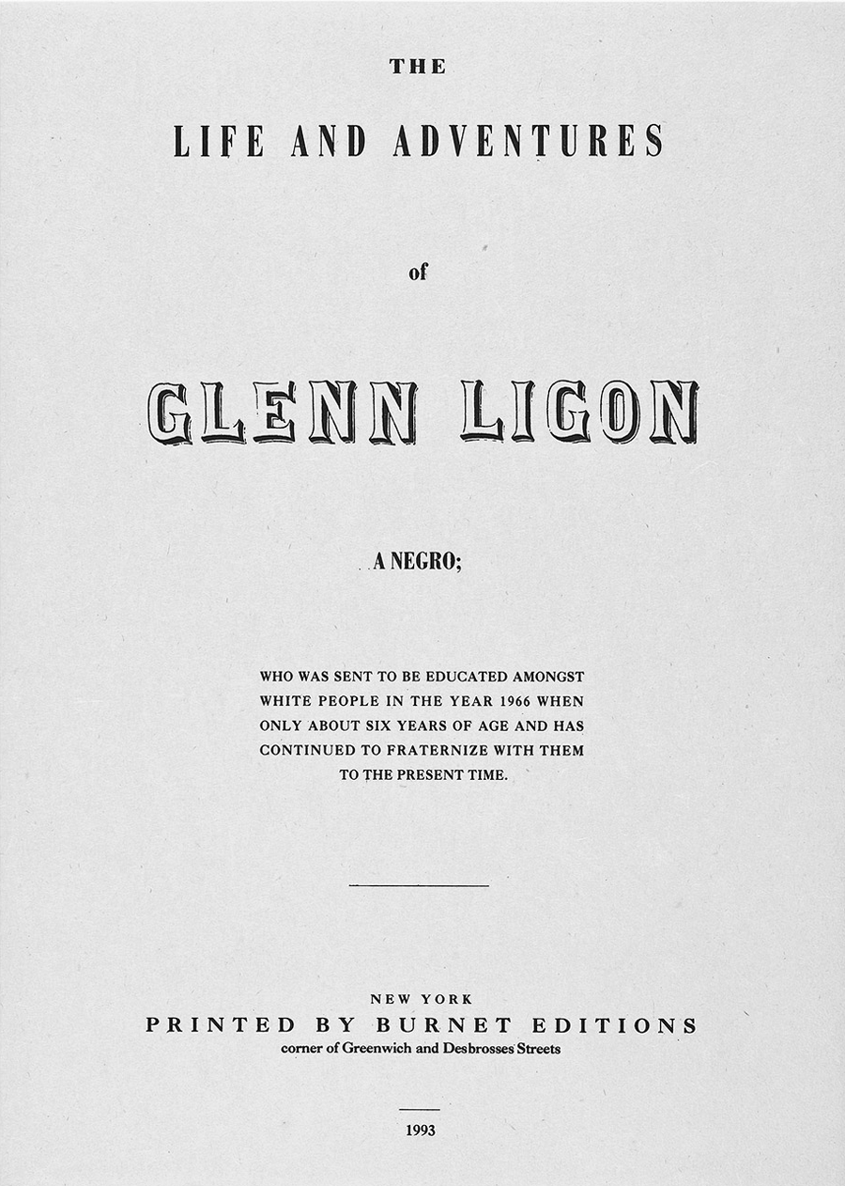

In 1993 visual artist Glenn Ligon debuted Narratives, a series of prints using eighteenth- and nineteenth-century slave narrative title pages as templates for ironic commentaries on contemporary American race relations. Reproducing the baroque form and syntax of the genres titles and typography but substituting his own autobiographical details in place of those of the ex-slave narrator, Ligon creates large mock-ups of imagined title pages, which provocatively link the conditions of contemporary African American art production with that of the literary production of fugitive slaves. One of the prints in the series, for example, The Life and Adventures of Glenn Ligon, A Negro, who was sent to be educated amongst white people in the year 1966, when only about six years of age, and has continued to fraternize with them to the present time, sends up viewers potentially inflated notions of racial progress by confronting them with the unexpected collision of nineteenth-century literary conventions and late-twentieth-century autobiographical disclosure ().

FIGURE 1. Print from Ligons Narratives series. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Glenn Ligon. The Life and Adventures of Glenn Ligon, A Negro, who was sent to be educated amongst white people in the year 1966, when only about six years of age, and has continued to fraternize with them to the present time (1993).

Using anachronism to open a space between Ligon-as-object (the Negro of the title) and Ligon-as-subject (the artist and subject of the autobiographical disclosure), Narratives challenges viewers expectations of black art and life, skewering the ways black cultural production has been consistently constrained and commodified to fit a market that does not always reflect the goals of black artists or writers themselves. By rigorously maintaining the formal elements of slave narrative title pages but supplying a contemporary subject and modern intertextual references, Narratives is a sly critique of the very notion of authenticity as it has been unequally applied to black artists and writers. Ligons historical displace

Ligons recovery of the publication conventions of slave narrative title pages allows him to critique contemporary constraints on African American artists while locating his art within a history of attenuated African American cultural production. Just as the ex-slave narrator entered into negotiation with white amanuenses or abolitionist editors and publishers, presenting his or her narrative to an overwhelmingly white readership, Ligon must weigh the benefits and constraints inherent in producing art in a gallery system dominated by historically white liberal institutions.Narratives illustrates the historical legacy of the negotiations the contemporary African American artist undertakes with the gallery and the public, drawn by Ligon as consumers of black distress.

Although Narratives presents us with, perhaps, the most explicit example, a diverse cadre of visual artists turned to slave narratives as fertile ground for contemporary cultural critique at the end of the twentieth century. In addition to Ligon, Kara Walker, Ellen Driscoll, Rene Green, David Hammons, Isaac Julian, Kerry James Marshall, Lorna Simpson, and Fred Wilson have all produced what I call contemporary visual slave narratives at the end of the twentieth century: works that combine nineteenth- and twentieth-century practices of visual representation with conventions of slave narration to question the historical threshold of legibility for the black subject.