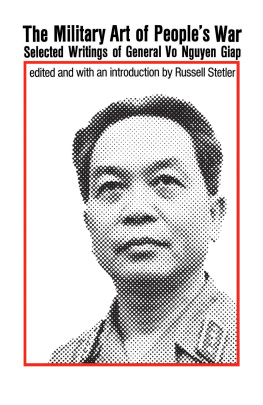

The Military Art

of Peoples War

The Military Art

of Peoples War

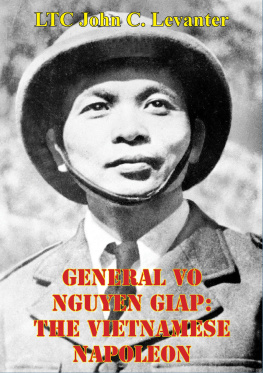

Selected Writings of

General Vo Nguyen Giap

Edited and with an introduction

by Russell Stetler

New York and London

Copyright 1970 by Monthly Review Press

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75105317

First Modern Reader Paperback Edition 1971

Monthly Review Press

146 West 29th Street, Suite 6W

New York, NY 10001

www.monthlyreviewpress.org

To the memory of Dr. Pham Ngoc Thach,

Minister of Health of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam,

who died in November 1968 at the front,

in fulfillment of the highest duties of an internationalist

and a revolutionary.

Acknowledgments

Many friends throughout the world helped in the preparation of this volume. While no one else bears any responsibility for the books shortcomings, many should share the credit for making it a more comprehensive volume. I am grateful to Mark Cook, Claude Henaff, Bruce Kuklick, Leonard Liggio, and Ray Ryan for helping to locate texts which could not be found in London. The staff of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation and the British Library of Political and Economic Science were efficient in providing texts and documents from their files and stacks. The most valuable cooperation and assistance came from the three London representatives of Vietnam Courier (Cuu Quoc), an information weekly of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. These three friends, Nguyen Van Sao, Nguyen Linh Qui, and Phan Due Thanh, gave generously of their time and repeatedly interrupted their busy schedules to see me to discuss the book. They furnished official translations of new texts very promptly, provided several photographs which we have reproduced here, and were an invaluable source of information for my introduction and footnotes. Another friend from the DRV, Colonel Ha Van Lau, took time out from his work in the Paris talks to discuss the early military history of the Vietnamese resistance and the genesis of General Giaps thought, and I wish to express my full appreciation of his help.

I also wish to thank Wilfred Burchett, Madeleine Riffaud, and Roger Pic for permitting me to include their interviews with General Giap in this volume. Pic kindly provided photographs as well, and I am very pleased that we were able to use them in the book. My discussions with Pic and Burchett over a period of several years have helped to clarify many of my ideas about Vietnamese military strategy and have given me a more vivid understanding of its application.

All the translations used in this volume are official, with the exception of the three interviews, which were conducted originally in French rather than in Vietnamese. In these three cases, my own translations, from authoritative French texts, appear. In the case of official translations, the reader will find some variation in style and quality. Some were carefully prepared for publication in English-language journals originating in Hanoi; others were produced more hastily for limited mimeograph distribution and were not originally intended for publication in book format. With these latter texts, we have therefore made occasional alterations, so that the particular article or essay will be more readable and the book as a whole more uniform.

Finally, I must thank Lesley Churchill, Sarah Poulikakou, and Terri Raymond for helping to type portions of the manuscript.

Contents

Introduction

In real life, Mao Tse-tung once remarked wryly, we cannot ask for ever victorious generals. This characteristic realism derives from decades of hard struggle, in which progress is measured not according to customary battle statistics or in terrain gained and held but in the persistence of the revolutionary forces, in their sheer capacity to survive over time. As in China, so, too, in Vietnam: the revolutionary forces have emerged the victors by showing their ability to endure protracted conflict. Vietnam has experienced nearly uninterrupted war since the mid-1940s, and the insurgents have had an ever widening impact. Set in deeper perspective, Vietnam has fought for its independence for two thousand years. Her statesmen frequently refer to this long history of resistance warfare, and they do so for more than rhetorical effect. Out of this long history a distinctive military science has evolved, with direct relevance to the present situation.

In all their wars, the Vietnamese have confronted a more powerful enemy, whether numerically, as in the case of the ancient Chinese, or technologically, as in the case of their contemporary opponents. A strategy of passive defense, in which one relies on fortresses and treats material resources and terrain as ends in themselves, has never worked. The Vietnamese suffered their own Dien Bien Phu five and a half centuries before the French, when the impregnable stronghold of Da Bang in the interior of Thanh Hoa fell under siege by the Chinese. The common features of the successful resistance wars stand out clearly. All relied on tactical, and often strategic, flexibility. (This conception was elaborated in the first Vietnamese handbook of the military professionin the thirteenth century!) All have utilized the natural advantages of terrain and environment to permit a mobile defense. All have utilized the expanse of time to the advantage

The inventiveness of the Vietnamese is well known. We are familiar with the use of thousands of bicycles to carry ammunition and supplies to Dien Bien Phu and with the tunnel warfare of the National Liberation Front. All this has a precedent in the Vietnamese past. In the 1780s, Quang Trung surprised an army of two hundred thousand Chinese by raising a massive army and bringing it five hundred miles in a month and ten days. He grouped his men in threes: in the long, swift march, two men carried the third between them in hammocks. Few in the West have comprehended the significance of this tradition. From a sociological and historical point of view, the Vietnamese are uniquely equipped to understand military dynamics and to fight the present war.

The contrast with American strategists and popular thinking is stunning. As secretary of defense in 1962, Robert S. McNamara stated: Every quantitative measurement we have shows were winning this war. It is fruitless to speculate on the extent to which successive administrations fell victim to their own propaganda: the Pentagon appears to be incapable of understanding the dynamics of peoples war. It is not so much that McNamaras statistics were exaggerated or even false. His military algebra is itself barren. America has been unable to endure the Vietnam war; yet this moral incapacity has never shown on the IBM punchcards. It was well understood in Hanoi long before the first GIs mutinied at Da Nang, for the Vietnamese understanding of war goes deeper than balance sheets and kill ratios. More than this, their senior strategist approaches, in real life, the status of an ever victorious general.

The life of Vo Nguyen Giap, taken as a whole, evinces remarkable energy and determination. Although he is less than sixty years old at

As a teen-ager, Giap was dismissed from school because of his role in the growing student movement. His involvement with the underground nationalist organization, Tan Viet (Revolutionary Party for a Great Vietnam), drew the attention of the police soon thereafter. In 1930, the entire Indochinese colony was shaken by an eruption of nationalist revolts. These events stirred young Giap, who had been recalled to Hue by the Tan Viet. The Vietnam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD), a nationalist party styled after the Chinese Kuomintang, began an abortive revolt with an uprising at the Vietnamese garrison at Yen Bai, along the Chinese border, on February 9. It was crushed ruthlessly, and the VNQDD virtually ceased to exist for the next fifteen years. The fledgling Communist Party attempted to maintain the revolutionary mood. When railwaymen struck at Vinh and other workers followed suit in the Ben Thuy match factories, the communists organized solidarity actions among the peasants in the provinces of Ha Tinh and Nghe An in Annam, who had themselves felt acutely the effects of the