HISTORY OF THE URBAN ENVIRONMENT

Martin V. Melosi and Joel A. Tarr, Editors

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2020, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-4593-2

ISBN 10: 0-8229-4593-2

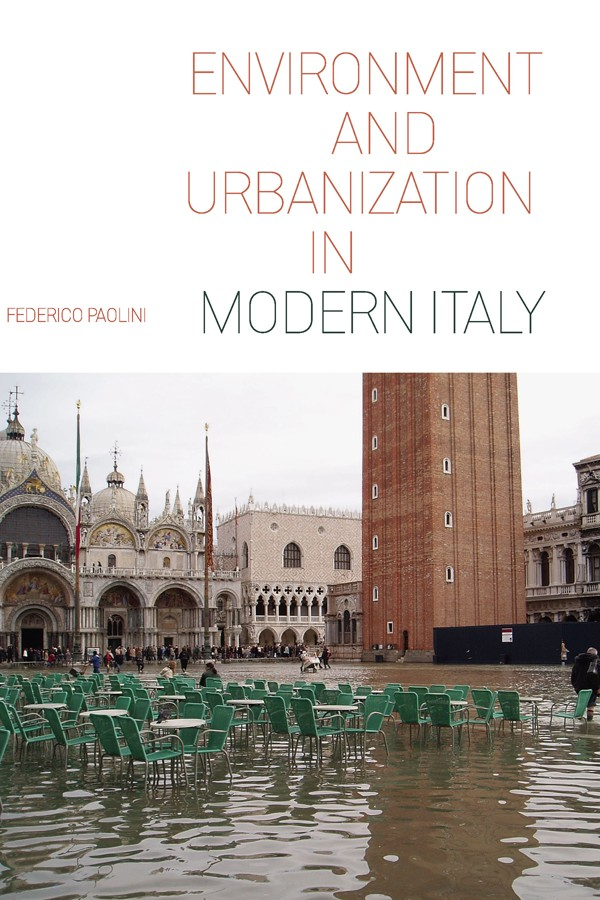

Cover photo: Acqua alta floods in Piazza San Marco, Wolfgang Moroder. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Cover design: Joel W. Coggins

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8725-3 (electronic)

INTRODUCTION

From the second half of the 1940s, when postwar reconstruction began in Italy, there were essentially three driving forces of environmental change. The first was apparent in the uncontrollable process of urban sprawl, fueled by considerable migratory flows from the countryside and southern regions toward the cities where large-scale productive activities were beginning to amass. The main consequence of demographic growth was an urban expansion modelfollowing an explosion in building favored by a cartel of interests that united builders, real estate professionals, landowners, and the investment bankscharacterized by the overseeing of scheduled settlements, by an infrastructural system tilted toward road networks, and by the lack of public services (e.g., greenspaces, public facilities). This model was repeated in all the cities that were spreading like wildfire, creating new urban areas built in a disorderly manner on portions of land set among industrial premises and inhabited chiefly by factory workers and their families.

The second driving force of environmental change was unruly industrial development, which was tolerated since it was seen as the necessary tribute to be paid to progress and modernization. The paradigm of modernization was understood as the path of exit from the rural condition, experienced as a condition of material scarcity in a static, restricted and introverted social and cultural context.

The second half of the 1960s saw the first manifestations of a third powerful driving force of environmental change: mass consumption. Failure to perceive that individual use of the environment generates a collective damage lay at the heart of the proliferation of the most common styles of consumption, such as the use of motor vehicles (which emit harmful substances that contribute to pollution of urban air and are partially responsible for the greenhouse effect) and the purchase of prepackaged goods (which contribute to the exponential increase in solid waste, whose disposal may generate metabolites dangerous to human health, such as dioxins). quickly prepared meals at limited costs), and also plastic materials, which made it possible to produce objects that rapidly became widely used.

As Jared Diamond has efficiently shown, the history of humanity offers numerous examples of environmental crises caused by collective behaviors and lifestyles of societies that were unable to measure the impact of their actions on the environment. On a par with the Danes in Greenland and the inhabitants of Easter Island, the postwar society repressed the environmental damage it was causing because it evidently saw the advantages produced by the development model as being far greater than the disadvantage of living in an ecosystem deeply modified by anthropic activities responsible for a growing environmental deterioration. Working in the factory, traveling by car, buying in supermarkets, living in newly built housing outside the old town centers, taking part in the rituals of consumer society (e.g., Saturday afternoon shopping, weekend trips, summer holidays at the seaside or in the mountains) were activities with a higher social value in comparison to the possibility of living in a more salubrious and less degraded ecosystem.