Originally published 1997 by City University Press

Published in 1999 by Transaction Publishers and arrangements with City University Press

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 by the author and City-universitetet, unless otherwise stated in a footnote on the first page of the articles.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 98-9390

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

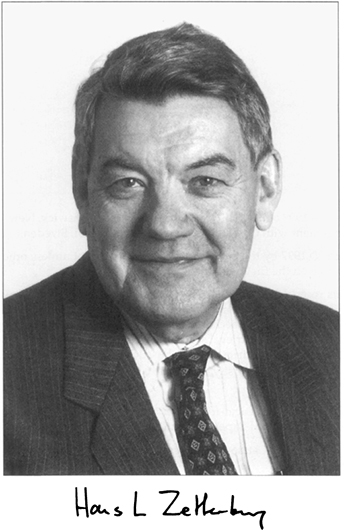

Zetterberg, Hans Lennart, 1927

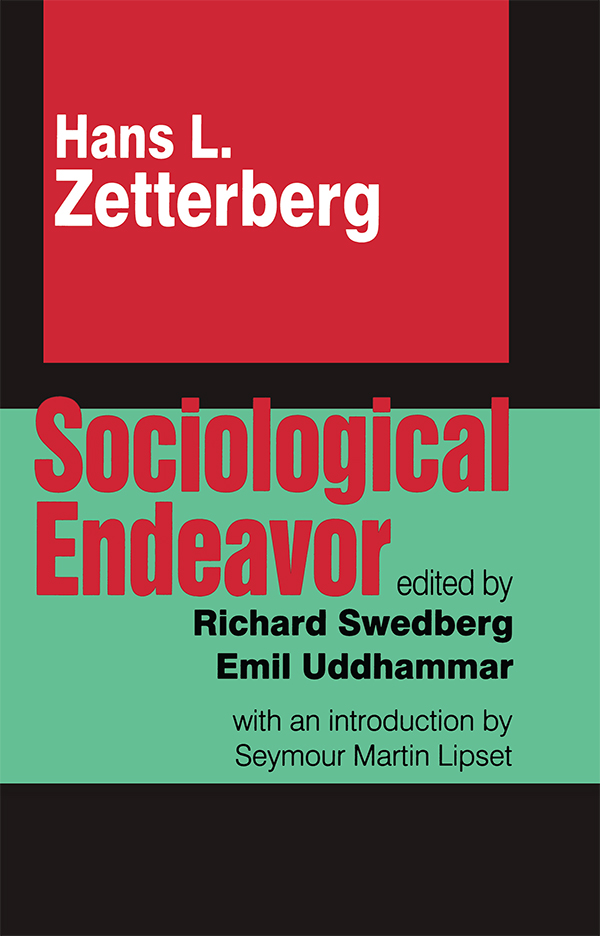

Sociological endeavor / Hans L. Zetterberg ; edited by Richard Swedberg and Emil Uddhammar ; with an introduction by Seymour Martin Lipset.

p. cm.

Originally published: Stockholm : City University Press, 1997.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56000-380-4 (cloth)

1. Sociology. I. Swedberg, Richard. II. Uddhammar, Emil, 1957 . III. Title.

HM51.Z46 1998

301dc21

98-9390

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-1-56000-380-9 (hbk)

It is hard to accept the fact that Hans Zetterberg is seventy. He looks much younger and is obviously still quite dynamic. But then I have to be cognizant of my own age even if, like Hans, I remain energetic and productive.

I first met Hans in the early 50s, when we were both new and young faculty members in what was then the most intellectually interesting sociology department in the world. Its senior members, Kingsley Davis, Paul Lazarsfeld, Robert Lynd and Robert Merton, were clearly world leaders. The self-conception of the department, including junior faculty and the graduate students, was that it was the center of world revolution, not politically of course, but not only in sociology, in social science generally.

The revolution was identified with Talcott Parsons and Robert Merton in theory and with Paul Lazarsfeld and Samuel Stouffer in methodology. Parsons and Stouffer, of course, were at Harvard. The theory, variants of structure functionalism, subsumed all that had gone before. The methodology, largely innovations in quantitative analysis and formal logic, involved great advances over the seemingly simplistic, more qualitative work done earlier.

Hans Zetterberg was a major contributor to the discussions and innovations in the 1950s. His linguistic abilities enabled him to be conversant with all the important European scholarship, and to bring these writings to bear on American social theory. He was also well trained in quantitative analysis, so that he could bridge work on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as the gap between qualitative work and quantification. This background gave him a unique and important perspective.

I left Columbia in 1956 to go to Berkeley. Hans ultimately returned to Sweden. That was the end of our interaction as colleagues. Before we separated, we planned to collaborate on a comparative study of social mobility, gathering survey data in a number of countries. We wrote a good proposal trying to secure funding, which summarized the literature and was, I believe, intellectually innovative, spelling out explicit hypotheses to be tested. Unfortunately, the foundations to which we applied did not see it our way, or perhaps thought the project would cost more money than they were willing to give to two young scholars.

We dropped the effort to finance the project, but we were able to rewrite the proposal into article form and presented it at the 1956 world sociology meetings. It was then published in the Transactions of that conference, and was later in revised form included as a chapter in Lipsets and Bendix Social mobility in industrialsociety (1959). Zetterberg, of course, was a co-author of the paper and chapter. The article is still worth reading today.

The most interesting or useful idea we presented is one derived from Thorstein Veblen, which we used to explain the comparably high rates of mobility in all advanced industrial societies as well as in post-feudal systems, which placed much greater emphasis on hereditary position and in less developed highly stratified poor agrarian societies. The empirical question we tried to answer, was the source of the motivation to improve position, to rise in such highly disparate cultures. Before Social mobility in industrial society was published, everyone expected higher rates of mobility in achievement in meritocratically oriented societies like the United States than in the more status (stand) bound systems of Europe and the Third World. Our hypothesis, however, was that all systems of stratification motivate the lowly to try to move up, because inequality, low position, is experienced as punishment, as social rejection, and therefore the less privileged always and everywhere try to take advantage of opportunities, whether by legal means or other, to improve their position. The latter part of the proposition, of course, was derived from Robert Merton.

This book, Sociological endeavor, is a good sampling of Zetterberg. , The confirmation and ordering of sociological propositions, taken from his influential work, On theory and verification in sociology, is pure Zetterberg as methodologist and theorist. On theory and the chapters included here should be must reading for aspiring sociologists.

, The historical differentiation of European Institutional Realms, is of particular interest to me as the author of a recent work on American exceptionalism, since Zetterberg defines the problem of this chapter as What is unique about European Civilization? He sees the continent as having a special path to social differentiation. Zetterberg focuses on the state and the church as the key institutions that structured Western European society in the Middle Ages. They resulted in six realms of freedom, economy, politics, science, religion, ethics and art. National independence gave rise to regimes which ultimately resulted in full freedom for individuals and associations. By contrast, Alexis de Tocqueville, and I following him, have, in trying to account for American exceptionalism or uniqueness, stressed the countrys emphasis on anti-statism and the resultant weak state, as well as the effect of voluntary and congregational, non-hierarchical, religion on the nature of American society. Zetterberg, in any case, by dealing with European uniqueness, provides a foil to analyses of American exceptionalism.