Contents

Page List

Guide

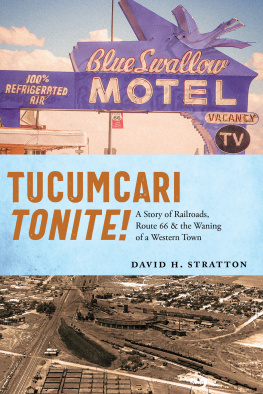

TUCUMCARI TONITE!

TUCUMCARI TONITE!

A Story of Railroads, Route 66, and the Waning of a Western Town

DAVID H. STRATTON

University of New Mexico Press | Albuquerque

2022 by David H. Stratton

All rights reserved. Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021953099

ISBN 978-0-8263-6339-8 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-8263-6340-4 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the Library of Congress

Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New MexicoPueblo, Navajo, and Apachesince time immemorial have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

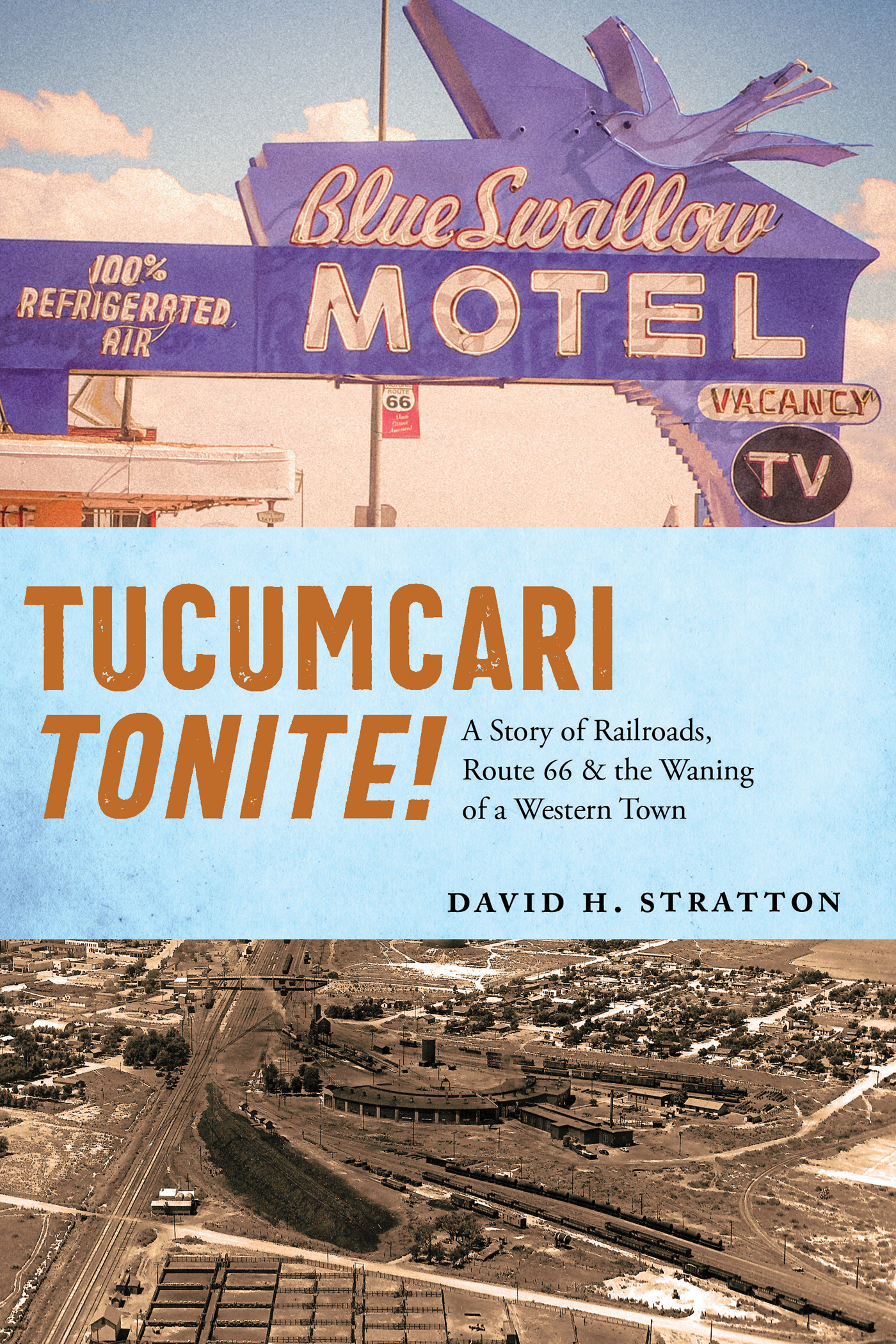

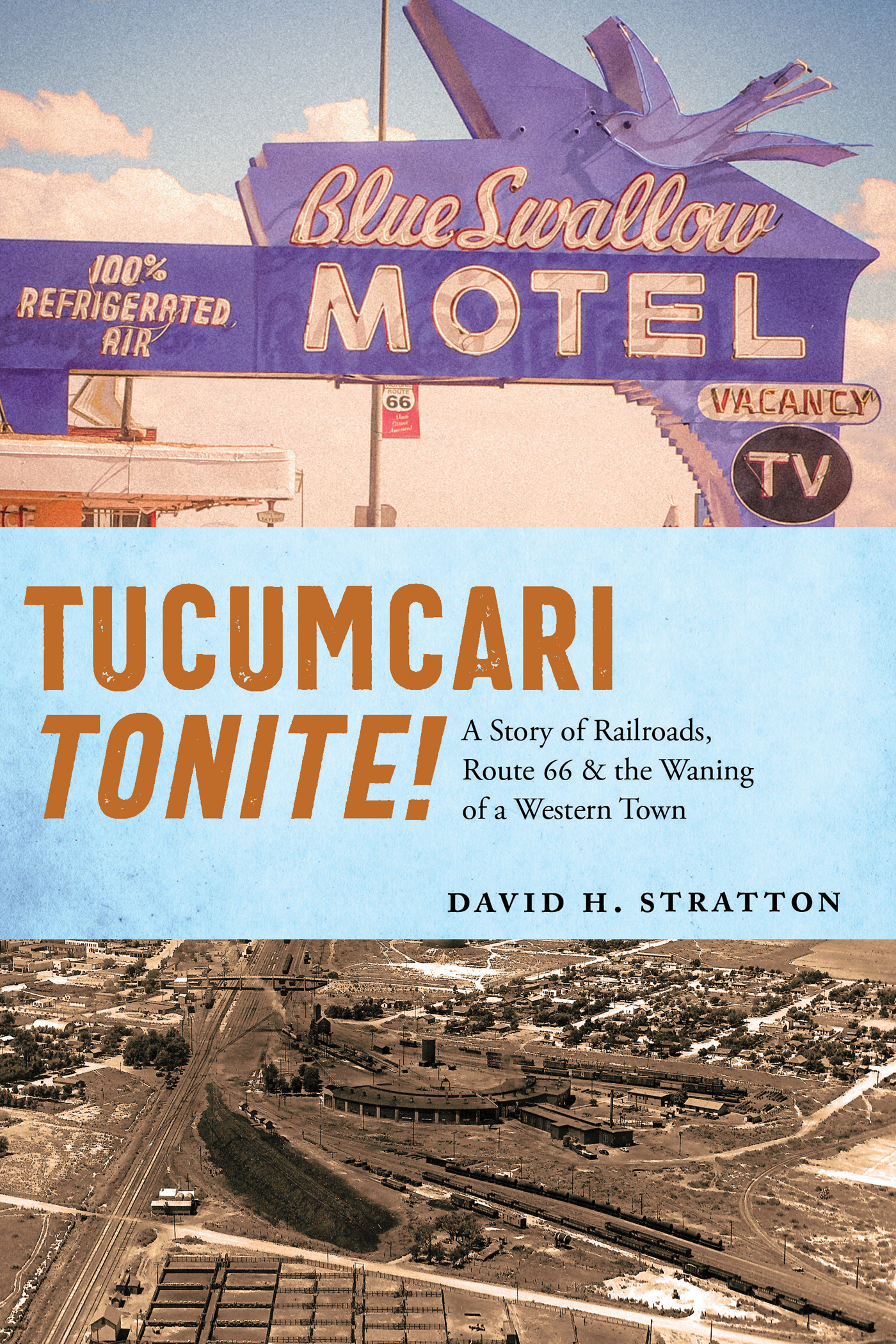

Cover illustration: (top) adapted from photograph by Mobilus in Mobili, licensed under CC by 2.0; (bottom) courtesy of Le Deane Studio.

Designed by Felicia Cedillos

To my children:

Nancy Stratton Hall, MEd, National Board-Certified Teacher

And to the memory of

Scott David Stratton, PhD

(19622014)

Michael J. Stratton, PhD

(19552016)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Lets face it at the outset. A book about an authors hometown sounds fishy. But this is not an account of high school romances or youthful exploits on the gridiron. Various world religions require their converts to make pilgrimages, usually to an especially important place associated with that particular faith. The purpose is a renewal of individual spirituality or, more simply, to give the pilgrims a sense of fulfillment, a realization of who they are, and the meaning of life through a journey back to the source of holy beginnings. The following account, although it may fall short as a pilgrimage, is neither a definitive history of a town nor my own coming-of-ageor, in this case, old-agememoir. For the most part it is a case study with scholarly intent of the influence of twentieth-century transportation development, largely of railroads and highways in the context of national trends, and its effects on one Western town. In short, besides railroads, the importance of early and modern roads, but particularly Route 66 and its successor Interstate 40, receive major attention.

Founded by the Rock Island Railroad in 1901, Tucumcari, New Mexico, became a regional rail center and division point where four lines converged and the Rock Island and the Southern Pacific met. Later, with the creation of the federal highway system in 1926, US Highway 66 ran through the middle of town. The period covered is mainly the twentieth century, although some parts run slightly beyond to give them a logical conclusion or for purposes of continuity. Tucumcari flourished as a railroad center and highway tourist mecca for most of the twentieth century, but it went into sharp decline as the century ended.

This account identifies, as the main interpretive explanation of Tucumcaris decline, the influence of powerful external forces that were at work, mainly those of a national technological and corporate industrial nature involving railroads as well as highway systems. On the other hand, largely to promote economic progress and offset external pressures, the town itself either employed certain internal forces or sanctioned outside initiatives that also contributed to the decline, particularly an urban renewal project that practically destroyed the original downtown business district. In short, Tucumcaris story is one that has been repeated countless times in small towns across the West and in other sections of the country as well.

It is important to note that I was born and raised two blocks south of US Highway 66, the fabled Mother Road and Main Street of America, when it was still filled with tourists getting their kicks on the way from Chicago to Los Angeles. In fact, in his monumental novel The Grapes of Wrath, about the exodus to California during the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Steinbeck coined the term mother road on the same page that he mentioned Tucumcari as a town located on the legendary highway. Also, where I grew up on South Adams Street was close enough to the rail yards that I could hear, night and day, the harsh, banging, steel-on-steel sounds of freight cars being coupled together. And in bed at night, I went to sleep to the sweet music of steam locomotive whistles as the mighty engines passed through or did switching duty locally.

When starting to write this book, I had the firm determination to avoid slipping into some sort of emotional relationship with the subject, on the order of a worshipful biography, and making my hometown an idyllic place like those depicted by Hollywood in the old Andy Rooney movies of the 1930s. I must confess that along the way I fell under the classical spell, as described by Plato (with allowances for paraphrasing), that the city is the soul of its citizens writ large. As a result, I sometimes bestowed human qualities, both virtues and vices, on the town as if it were a person. In fact, toward the end of my scholarly efforts, while mulling over an analysis of Tucumcari history, I realized that, indeed, I did actually love the place, a sentiment that had once surfaced in an awkward, although sincere, expression of my feelings. I could imagine myself

Running across the grey prairie

Through yellow-beaned mesquite and squat prickly pear cactus bearing scarlet fruit

Down ferrous-red arroyos and past purple-walled mesas

Up steep canyon slopes wrinkled like cowhide and dotted with scrub junipers

Over the rocky Eyebrow

To the endless Llano stretching away over the horizon.

I have no excuses for my sentimental attachments to Tucumcari, past or present, nor do I intend to make any now. In fact, I believe that my personal involvement with the subject of this book has given me important insights that a more detached writer would lack. At the same time, I pledge that my emotions did not take the place of more sober scholarly judgments of my old hometown, even though there was always room for both.

The reader will notice a heavy reliance on local newspapers for source material in this account. This is the case because the subject has a large element of local history and also because, for most of the twentieth century, the Quay County newspapers recorded everything the editors considered as important in the community they servedand beyond. It is true that these publications almost always remained in a booster mode, which required careful interpretation, but by concentrating on reading between the lines, it was possible to ferret out the essential information. Otherwise, in dealing with an astute editor and colorful personality, like Paul Dodge of the Tucumcari Daily News, it was easy to trust most of his news and views as being reliable. Large segments are also told through the personal experiences of notable women, men, and ethnic and racial groups. Conventional source materials, such as government documents, manuscript collections, interviews, and memoirs, provide a large part of the information. Since my parents and grandparents came to the area soon after Tucumcaris founding, and I have always called it my old hometown, their recollections, as well as my own, are a vital part of this book. Overall, it was my intent to write an informative narrative of a Western towns involvement with railroads and highways that brought less than happy results.