Sex Dolls at Sea

Media Origins

Edited by Elizabeth Losh and Celia Pearce

Numbered Lives: Life and Death in Quantum Media, Jacqueline Wernimont, 2018

Sex Dolls at Sea: Imagined Histories of Sexual Technologies, Bo Ruberg, 2022

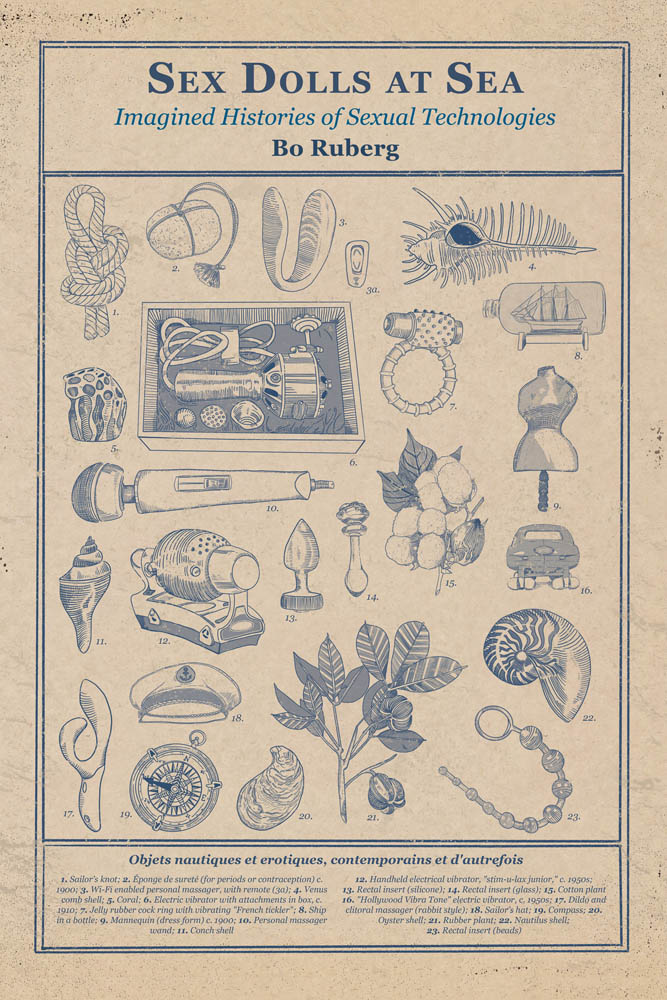

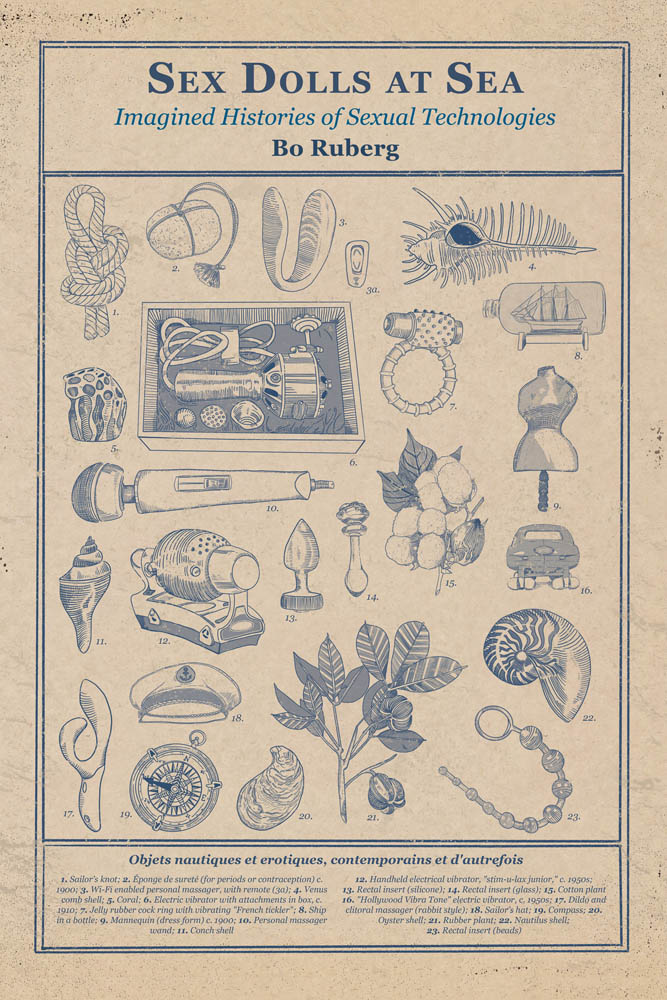

Sex Dolls at Sea

Imagined Histories of Sexual Technologies

Bo Ruberg

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This work is subject to a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license.

Subject to such license, all rights are reserved.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ruberg, Bonnie, 1985- author.

Title: Sex dolls at sea : imagined histories of sexual technologies / Bo Ruberg.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2022. | Series: Media origins | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021033923 | ISBN 9780262543675 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Sex dollsHistory. | SexSocial aspects. | Sex (Psychology) | Sex in mass media.

Classification: LCC HQ23 .R83 2022 | DDC 306.77dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021033923

d_r0

For Jonah, who, like me, has always loved the water

Contents

Media Origins is a venue for interdisciplinary, humanistically informed research that recovers and interrogates the origin stories of contemporary media technologies. The titles address a range of cultural objects in the history and prehistory of computation. The series explores the politics of design and labor, the role of economics more broadly imagined, and the cultural frameworks of shared meaning making that undergird not only innovation but also maintenance, consumption, and disposal. Such origin stories often examine precomputational precursors to understand the larger social patterns, values, and beliefs behind a given mediums trajectory into the contemporary technological milieu. Volumes in the series may deploy feminist, postcolonial, queer, or antiracist theory to foster deeper conversations about the framing narratives of innovation.

The Media Origins series cautions that, in its obsession with the new, new media have developed an alarming ahistoricism that puts media studies at risk of losing valuable and largely undocumented accounts, particularly when cultural memory resides in rapidly aging witnesses or in records that are precariously stored in informal or neglected archives. Rather than reinforce assumptions about the technological survival of the fittest based on market metrics, the series excavates foundational platforms that have been all but ignored due to their perceived lack of commercial success.

Media Origins was launched to counter historical narratives that tend to emphasize the inventor myth, crediting a lone auteur. Unfortunately, overtelling one origin story usually comes at the expense of often-marginalized groups and participants that were instrumental at inception or adoption. Equally damaging to understanding media origins can be the reification of artifacts with little attention to the larger discursive contexts of their invention, manufacture, and adoption. In looking at the interactions between actors and objects, books in the Media Origins series may revise existing views about the dynamics of power and control, specialization and distribution of labor practices, or systems of credit.

The process of researching and writing this book has often felt like a solitary one, the result of many months spent hiding away in my office, pouring over documents, delving deeply into archives, and thinking about the relationship between technology, sexuality, and this odd thing we call history. In reality, this project has come into being through the generosity and support of many peoplein no small part because much of my work has taken place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of these people have been my collaborators, colleagues, and friends. Others have been archivists and librarians. A number of others have lent me their assistance even though we have no official professional ties. For a number of years now, I have been that stranger on the internet sending cold-call emails about sex dolls to anyone I had reason to believe might hold a clue I could use in my search for the dames de voyage. To my great benefit, almost all of them answered, and I learned something new from each one.

A number of the scholars whose work I discuss at length in the early chapters of this book have generously replied to my queries about their sources and shared with me some of their unpublished works. Among these are Cynde Moya, Anthony Ferguson, David Levy, Amy Wolf, and Hallie Lieberman. I am also grateful to Minsoo Kang for his thoughts on the veracity of the tale of the dames de voyage, as well as to scholars and archivists of maritime history Gina Bardi, Peter Kasin, Gibb Schreffler, and Amy Parsons for their expert guidance. My thanks to Andrea Horbinsky and Zoyander Street for their assistance with my research into the textual lineage behind the story of the Dutch wives, specifically in verifying my readings of Japanese-language texts. Relatedly, thank you to Kathryn Levine and Aubrey Gabel for indulging me and reading a schlocky serialized short story from the 1890s so that we could double- and triple-check the context meaning of references to dames de voyage.

Thank you to Elizabeth Losh and Celia Pearce, the editors of the Media Origins series, for believing in this project even in its nascent stages and for supporting my vision of a book that is somehow simultaneously quirky and serious, highly specific and extremely wide-ranging. My gratitude also goes out to my editors at the MIT Press, first Doug Sery and now Noah Springer, for their encouragement and support through the publishing process. I am thankful for the work of my anonymous peer reviewers, who offered feedback at multiple stages, including during the hubbub of the pandemic. Their feedback on the original full draft of the manuscript, which was admittedly still rough, was invaluable. I am especially grateful to my most exacting reviewer, whose careful engagement with the manuscript draft was exactly the push I needed to make this into the book it is today.

Librarians, archivists, and curators are the true heroes of this project. My enormous thanks to Jenna Dufour, research librarian for the visual arts at the University of California, Irvine. I have lost track of the number of times I have emailed Jenna in a state of exuberance or panic to ask for help tracking down some obscure sex-related document. The Humanities and Rare Books Reference Teams at the British Library, and Elias Mazzucco in particular, went above and beyond to help me track down the album of advertisements for sex toys discussed in chapters 2 and 4. Despite a series of obstacles, from pandemic travel restrictions to the realization that the documents in question were too fragile for reproduction or public viewing, the British Library staff was able to send photos at the eleventh hour that I was so happy to receive that I spent a whole morning alone in my office laughing with delight.

Next page