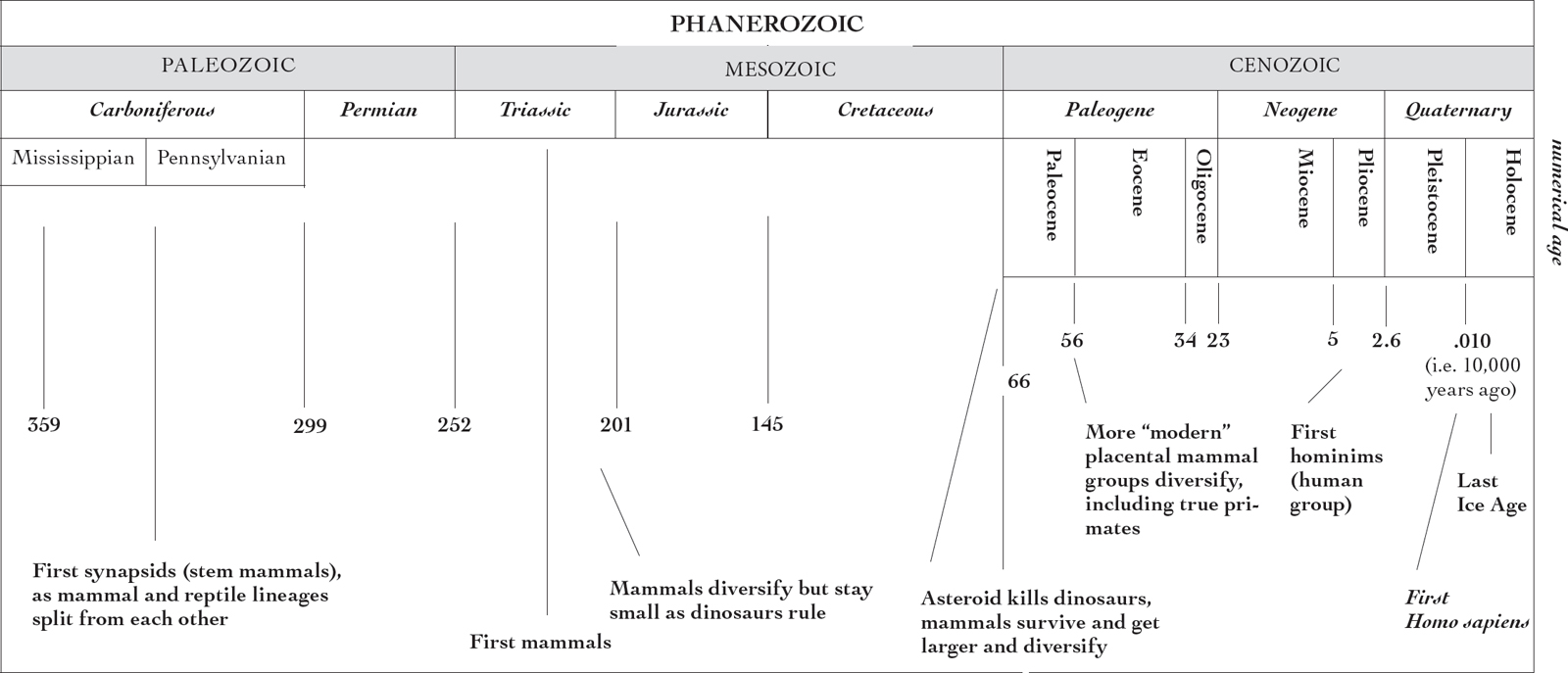

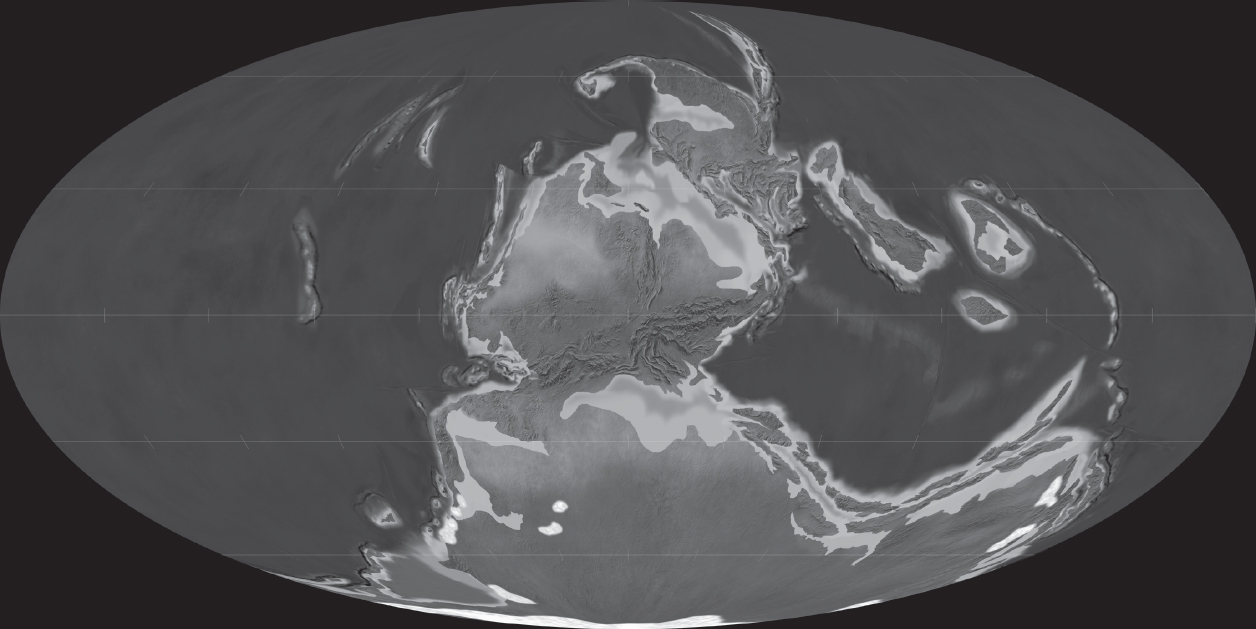

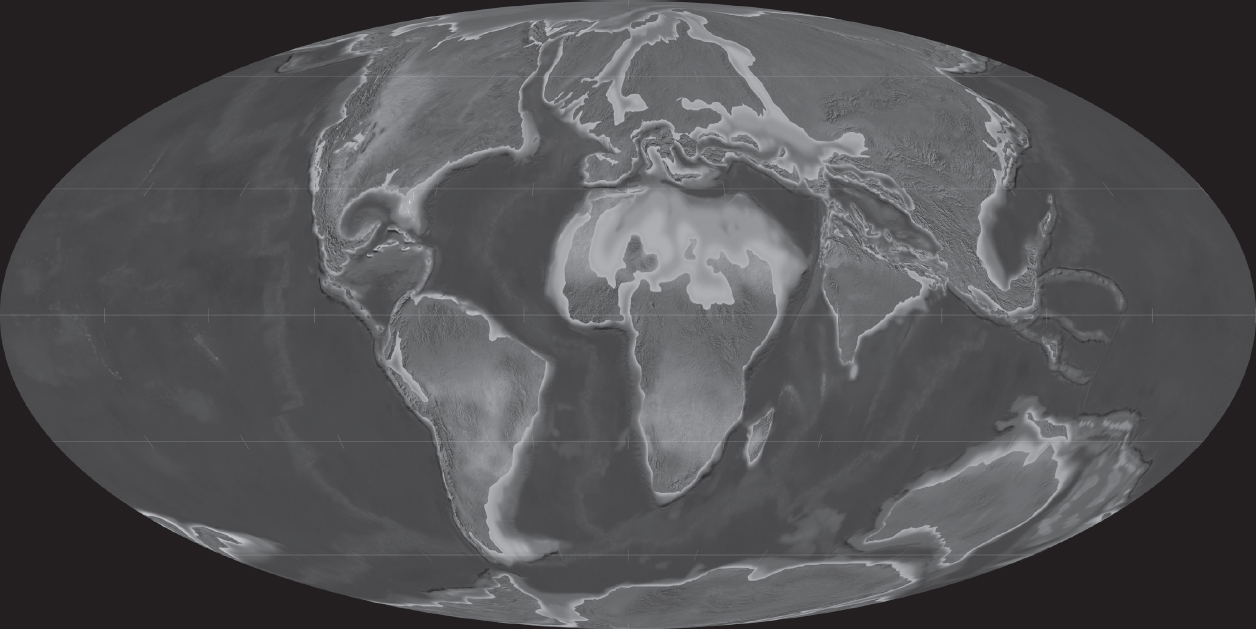

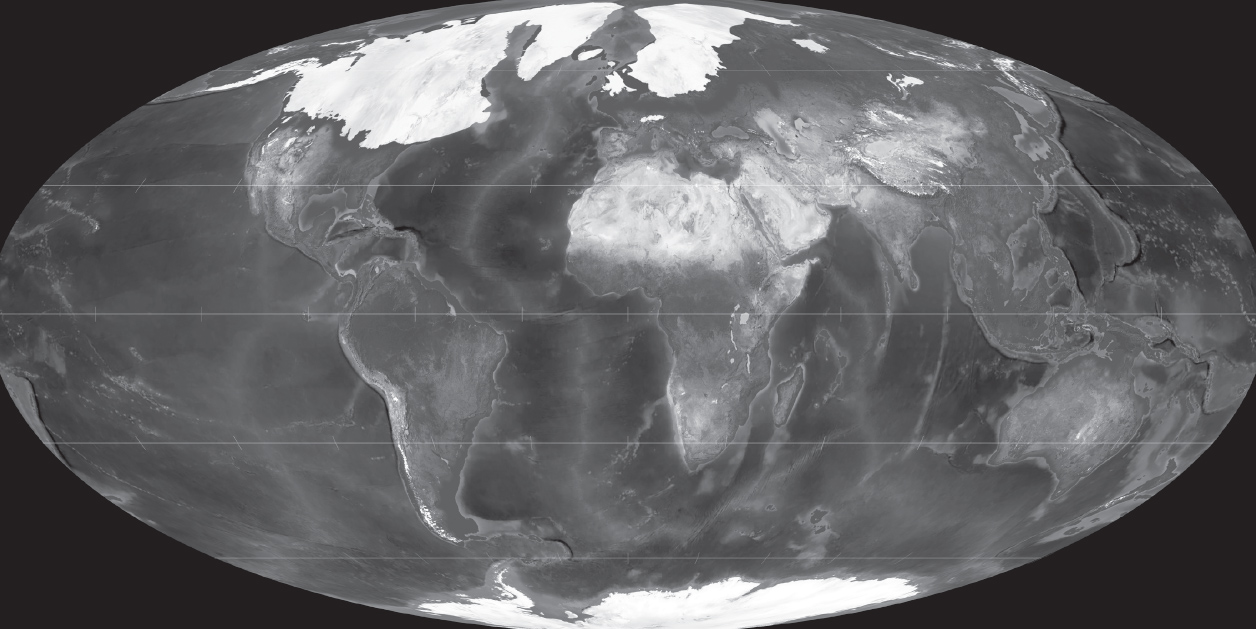

21,000 years ago, last advance of the Ice Age

FOR THE FIRST TIME IN years, the sun broke through the darkness. There was still a whiff of smoke wafting from the gray clouds, which blanketed the ground in shadow. Down below, the land was wrecked. It was all dirt and mud, a wasteland absent any greenery or color whatsoever. Silence hung in the wind, punctured only by the churn of a river, its currents clogged with sticks and stones and the residue of decay.

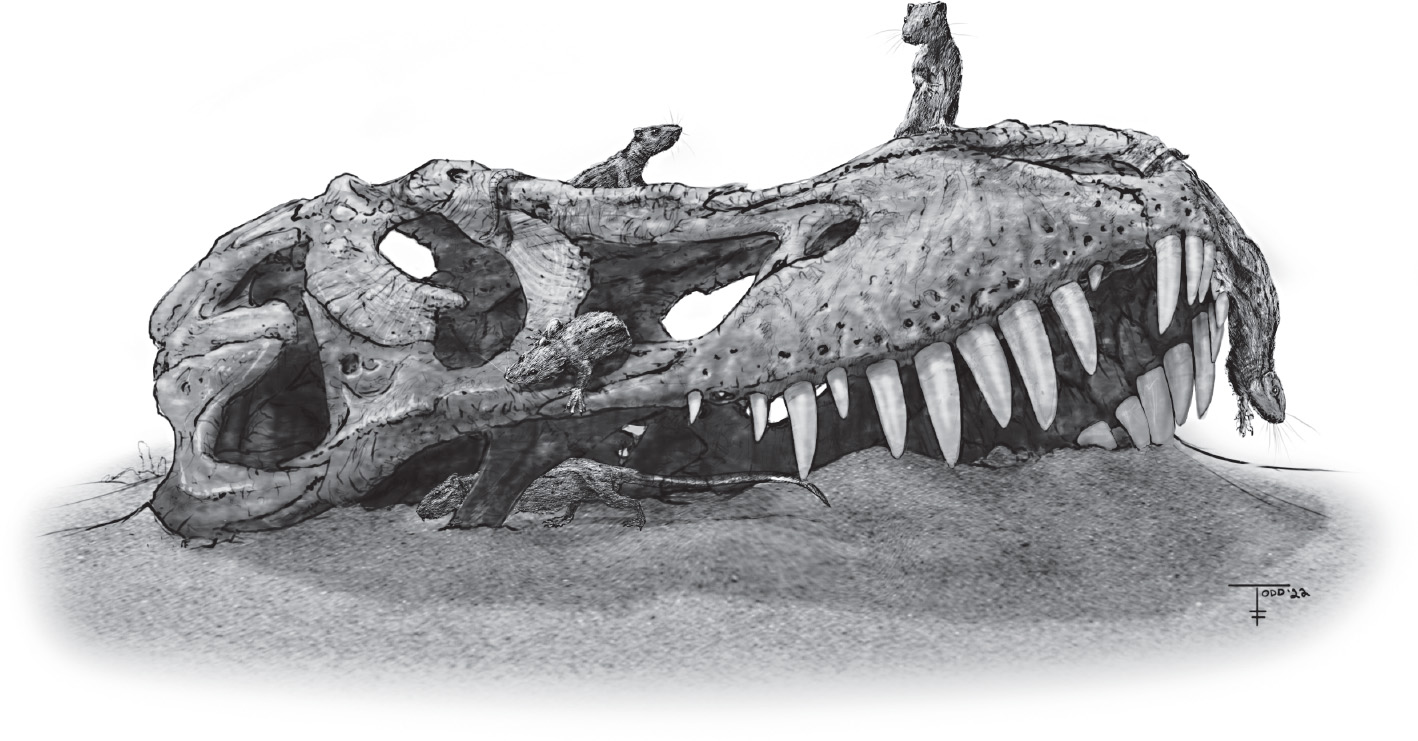

The skeleton of a beast lay upon the riverbank. Its flesh and sinew were long gone, its bones a moldy beige. Its jaws were agape in a scream, its teeth busted and scattered in front of its face. Each one the size of a banana, with the sharp edges of a knife, the murder weapons this monster had used to dismember and crush the bones of its prey.

It was, once, a Tyrannosaurus rex, the tyrant lizard, the King of the Dinosaurs, the oppressor of a continent. Now its entire species was no more. And little else seemed to be alive.

Then, from somewhere within the behemoth, a soft sound. A clicking chatter, a flutter of footsteps. A tiny nose poked out between a couple of T. rex ribs, haltingly, as if afraid to go any farther. Its whiskers trembled, in expectation of danger, but it found none.

Time to come out of hiding. It leapt upward, into the light, and scurried onto the bones.

Clothed in fur, with bulging eyes and a snout full of teeth that looked like mountain peaks and a whiplash tail, this critter couldnt have been more different than a T. rex.

It paused for a moment to scratch the hair on its neck, turned its ear to the air, and scampered forward on all fours. Hands and feet planted firmly underneath its body, it moved fast, with purpose. Up the rib, across the backbone, and onto the dinosaurs skull.

There, on the side of the head, where the eye of this T. rex once glared at herds of Triceratops, the furball stopped. It looked back in the direction of the rib cage, and let out a high-pitched squeak. From the bowels of the beast, out bounded a dozen smaller furballs. They raced toward their mother, and latched onto her belly, lapping up a breakfast of milk as they experienced their first minutes aboveground.

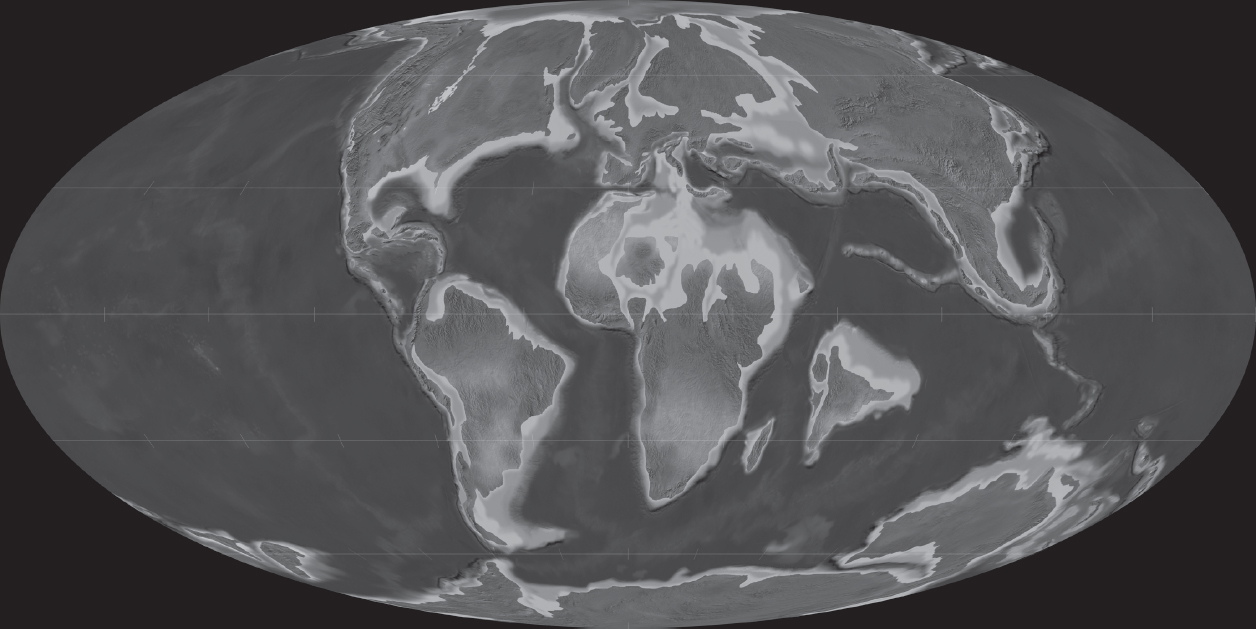

As she nursed her babies, the mother stared into the sunlight. The world now belonged to her, and her family. The Age of Dinosaurs was over, put to rest with the fiery destruction of an asteroid and a long, dark, global nuclear winter. Now the Earth was healing. The Age of Mammals had begun.

SOME 66 MILLION years later, more or less, another mammal stood in the same spot, swinging a pickaxe. Sarah Shelley was my first PhD student after I started my job as a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. We were in New Mexico, on a fossil hunt, searching for the bones and teeth and skeletons that would help us understand how mammals survived the asteroid, outlasted the dinosaurs, and made the world their own, becoming the furry animals that we know, love, and sometimes fear today.

Mammals are the most charismatic and beloved creatures on the planetwith all due respect to reptiles and birds and the other eight-million-plus animal species that are not mammals. Perhaps this is because many mammals are simply cute and fluffy, but in part, I think its because, on a deeper level, we can relate to them, and see ourselves in them. The cheetahs and gazelles locked in chase on the television screen, as David Attenboroughs dulcet tones narrate the drama. The mother otter playing with her pups on the cover of a nature magazine. The elephants and hippos that make every child beg their parents to take them to the zoo, and the endangered pandas and rhinos that pull at our heartstrings when so many other appeals for charity might annoy us. The foxes and squirrels that tolerate our cities, the deer that encroach on our suburbs. Whales with bodies longer than basketball courts, emerging from the abyss to spray blowhole geysers several stories into the sky. Vampire bats that literally drink blood, lions and tigers that make our hair stand on end. Our cuddly pets, of the feline or canine or sometimes more exotic variety. For many of us, our foodbeef burgers, pork sausages, lamb chops. And, of course, us. We are mammals, in the same way that a bear or a mouse is.

As a porcupine shaded itself from the New Mexico afternoon in the nook of a cottonwood, and a colony of prairie dogs chirped in the distance, Sarah brandished her pickaxe. Each strike into the rock released a haze of foul, sulfur-smelling dust. Each time she would wait for the dust to clear, to see if anything interesting had loosened from the Earth. For at least an hour, each strike brought only more rock. Until, with one thwack, something with a shape, a different texture, a different color poked out. She knelt down to take a look. And then hollered a victory cheer so loud, and so happily profane, that I cant repeat it here.