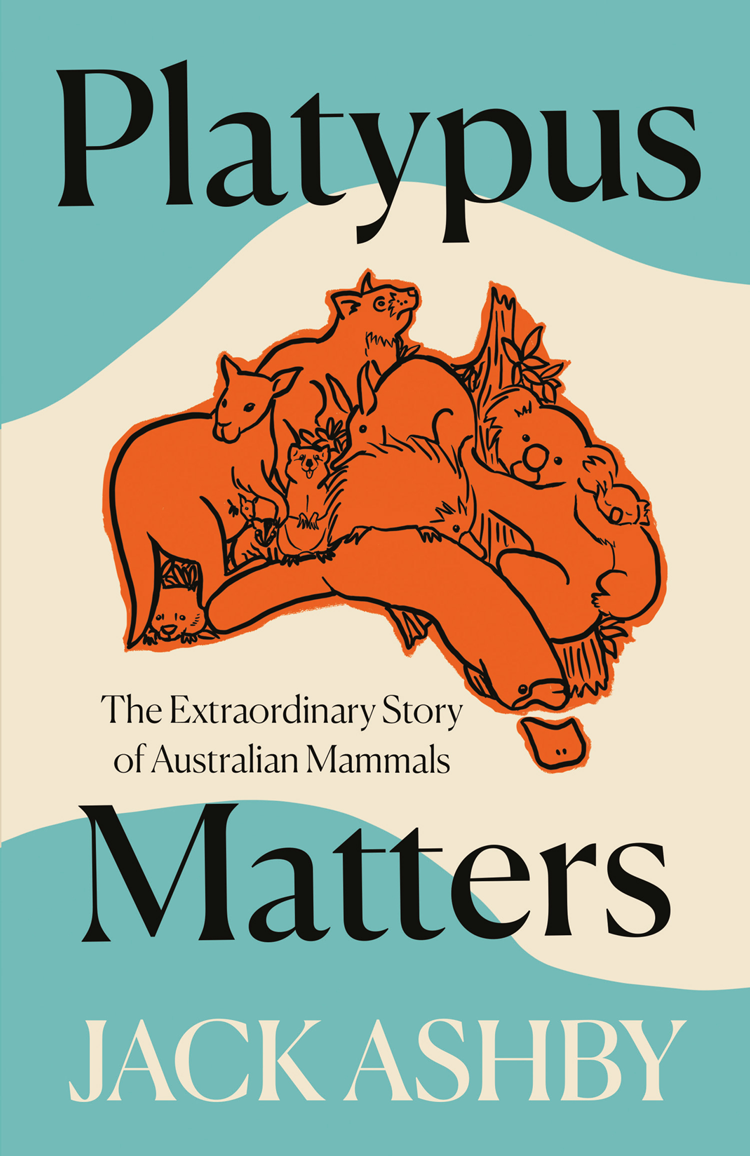

PLATYPUS MATTERS

The Extraordinary Story of AustralianMammals

Jack Ashby

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

First published in the United States by the University of Chicago Press in 2022

Copyright Jack Ashby 2022

Images individual copyright holders

Cover design and illustration by Jo Thomson

Best efforts have been made to attribute quotes to individuals, institutions and organisations mentioned in the references and acknowledgements. Any inadvertent mistakes or omissions will be gladly rectified in future editions.

Jack Ashby asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008431433

Ebook Edition March 2022 ISBN: 9780008431457

Version: 2022-03-24

To Australias naturalists,

past, present and future.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains names of individuals who are now deceased, and references to terms and descriptions that may be culturally sensitive or considered inappropriate today.

Contents

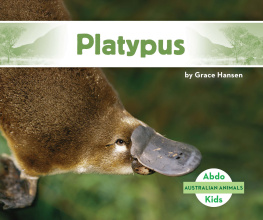

Ever since I first encountered them as museum specimens at university, platypuses have been my favourite animals. It may seem childish that a grown adult particularly one that works in science has a favourite animal, and perhaps it is, but the more I learn about them, the more I am convinced that nothing more wonderful has ever evolved.

Following those undergraduate classes, finding platypuses in the wild shot straight to the top of my zoological to-do list. All zoologists have these biological bucket lists and they typically define how nature-nerds spend their time, working hard to find and observe the animals that fascinate them most.

As well as platypuses, my list also includes species that are relatively widespread and found closer to home. For example, over the years I have spent what adds up to several fruitless weeks sat at the edge of countless British bodies of water failing to see a Eurasian otter (the closest thing we have to a platypus, ecologically speaking), until I finally found one in a stream running through the middle of the town of Frome in Somerset, while teenagers loudly performed donuts in the supermarket parking lot right alongside.

It sometimes feels as though these hard-earned encounters divide ones life into discrete chunks. Before you were stared down by a family of snow leopards and after you were stared down by a family of snow leopards. At other times, though, these moments can be deeply frustrating: I only know that I have been in the presence of a sloth bear from seeing the two reflective dots of its eyes as it noisily snuffled for fallen fruit in the pitch black beyond the limits of my torchlight. To have continued closer would have been foolish with such an unpredictable and well-clawed animal.

Less dangerous, my first wombat sighting caused me to start shrieking excitedly at the driver on a packed bus as we sped past the animal I had dreamed about seeing for years. She didnt stop the bus, and I was heartbroken that the encounter was so fleeting. Until, that was, we got off at the next stop and found perhaps fifty wombats wombling around the immediate area. Each moment with a sought-after species becomes burnt into the memory like other significant life events.

For me, the idea of a zoological bucket list isnt about ticking boxes on an animal bingo card. Working with museum specimens, reading descriptions or watching footage can only go so far in furthering our appreciation for a species. We can never hope to truly know an animal, only to try, but nothing beats seeing them being there with them on their own terms and in their own environment as they go about their business. An exercise in list-ticking would involve being satisfied by just a single encounter, before moving on to the next species down the list. Instead, finding a passion species typically means you want to keep working to see them again.

A year into my first proper job at the Grant Museum of Zoology in London, I had saved enough money for a return flight to Tasmania to search for the first animal to make my list: the platypus.

In our first few days in Tasmania, my friend Toby Nowlan (now a wildlife filmmaker) and I managed to find wombats, Tasmanian devils, quolls (slender, spotted mongoose-like relatives of the Tasmanian devil) and echidnas (platypuses spiny ant-eating relatives), but had not set eyes on a platypus. We were walking the Overland Track across the Tasmanian highlands one of Australias great long-distance treks at the height of summer. This week-long hike takes you through temperate rainforest, buttongrass moors and mountain passes, and via many lakes and streams that are perfect for spotting platypuses.

Unfortunately, the Overland Track in summer is so beautiful that it is also extremely busy. Every evening we would head for the nearest body of water and look for platypuses, only to find that other walkers had made it there first for a relaxing swim, which reduced our chances of success to zero.

Tasmania is famous for its ability to swing rapidly from T-shirt weather to freezing conditions, even in midsummer. On the penultimate leg of the trek on the day before Christmas Eve the weather broke for the worse, and it started to snow. The days route took us down out of the mountains, descending to the northern tip of leeawulenna, or Lake St Clair, Australias deepest lake. With the drop in altitude, the snow turned into rain. Torrential, rainforest rain. We were thrilled: with the other walkers sheltering safely in the nearest hut, Toby and I waited for evening and headed to the lake.

As mammals, foraging platypuses must return to the surface to breathe, giving platypus-watchers a few seconds of precious viewing interspersed with what feel like interminable periods when you fear that they have disappeared into their burrows. Such brief appearances are probably for the best, though, if like me you involuntarily stop breathing while they are in sight. Holding ones breath could be wise, however, as platypuses are extraordinarily sensitive to both movement and sound when at the surface. The tactic for approaching them is like a childrens party game: you creep closer, but if the platypus sees you move, youre out.

Platypuses are small, so the challenge is to get close enough to get a good look. While they are underwater, you can move and communicate with your fellow watchers as much as you like, because the platypuses eyes and ears are closed. But when the platypuses are on the surface you must become a silent statue, or they will disappear. Game over.