Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

A is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Suspicious Minds by Rob Brotherton

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

The Planet Factory by Elizabeth Tasker

Catching Stardust by Natalie Starkey

Seeds of Science by Mark Lynas

Nodding Off by Alice Gregory

The Science of Sin by Jack Lewis

The Edge of Memory by Patrick Nunn

Turned On by Kate Devlin

Borrowed Time by Sue Armstrong

The Vinyl Frontier by Jonathan Scott

Clearing the Air by Tim Smedley

Superheavy by Kit Chapman

The Contact Paradox by Keith Cooper

Life Changing by Helen Pilcher

Sway by Pragya Agarwal

Bad News by Rob Brotherton

Kindred by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

Mirror Thinking by Fiona Murden

Our Only Home by His Holiness The Dalai Lama

First Light by Emma Chapman

Ouch! by Margee Kerr & Linda Rodriguez McRobbie

To my favourite mammals of all, my family.

If you are reading this book, I probably dont have to convince you that fossils are interesting but are they useful ? Is palaeontology the dinosaur of science? Can old bones provide information relevant to the modern world?

When I began my palaeontology Masters degree, we started with a lecture in which my professor himself the author of multiple books on the topic opened with the famous quote attributed to Nobel Prize-winning scientist Ernest Rutherford: All science is either physics or stamp-collecting. No prizes for guessing what he studied. My professor spent the lecture explaining the many reasons why palaeontology was no mere hobby. I remember being puzzled; it hadnt occurred to me that anyone would ever think this way. Surely all science is created equal?

There is a perception that the study of palaeontology is just the study of a bunch of dead things. Apart from entertaining children, it can appear at first glance as though theres little to it but describing dusty bones, hacked from the Badlands by men in wide-brimmed hats. Many people believe it is all about dinosaurs. I know a five-year-old who would love to meet you! people say to me. Thats lovely, I reply, but do you know any forty -five-year-olds I could speak to?

Fossils are unique for the insights they provide into the deepest origins of life on Earth. They yield answers to questions that molecules can never address. At first blush, bones and teeth betray the presence and absence of organisms when did certain groups appear and disappear (or at least, what is the earliest or latest we know they certainly lived), and where did they inhabit? Next, they give us information about taxonomy, the study of how different groups are related to one another, which provides a framework for our understanding of all animal relationships. Fossils tell us how diverse animals and plants were at different times in the past, and the changing environments they inhabited. We can then use them to chart the outlandish journey evolution has made: natural selections incremental tip-toeing and occasional leaps. We can also chart fluctuating climate and atmosphere, ocean acidity and temperature, and the function and fecundity of ecosystems. Taken together, this information allows us to identify evolutionary patterns taking place across geological time on a global scale. As we face what has been rightfully named the sixth mass extinction a human-made natural disaster it has never been more vital for scientists to know how life has responded to extinction events in the past, and most crucially, how it has recovered.

But going beyond that, these old bones can tell us how extinct animals once moved . Did they run, hop or slither their way across the face of the Earth? And what was their role in their environment, their ecology ? This kind of information has been inferred for centuries via observation of skeletons, but we can now compute enormous datasets of bone shapes and test those hypotheses about form and function mathematically. We can even nick a few tricks from engineering, taking methods used to test the strength of building materials and applying them to fossils to understand their capabilities. The methods and results of these transformative new analyses have applications for human and veterinary medicine, for conservation and ecology, and of course for our knowledge of extinct life itself.

If you still have that Indiana Jones picture of the palaeontologist in your mind or even Ross from Friends you couldnt be more wrong. Forget whips, what real palaeontologists carry with them is their laptop. They may need a hat for occasional fieldwork, but most would do better investing in a comfy office chair because theyll be spending most of their lives in front of a computer. Coding is a vital tool in the kit, allowing them to gather enormous volumes of information and statistically analyse it. They type code like most of us type text messages. They fetch CT scans like ordinary people grabbing a takeaway coffee.

We are now seeing a radical transformation in the science of extinct life. That is part of the reason that I am writing this book. The use of statistical methods to analyse big data and the routine CT scanning of fossils have opened up entirely new fields of research. Our knowledge has accordingly exploded out of the boundaries to which pen, paper and a keen eye had previously confined it. The role of women is finally being recognised, both in the past and in the present. There is still a long way to go to address the diversity balance in palaeontology (as in other sciences) were still a little too white and Western. But increasingly, the countries where the most ground-breaking discoveries are being made are not Europe and America, but China, Madagascar, South Africa, Argentina, Brazil. Researchers from those countries are studying their own fossil heritage, rather than seeing it removed to museums abroad, as was once habitually the case.

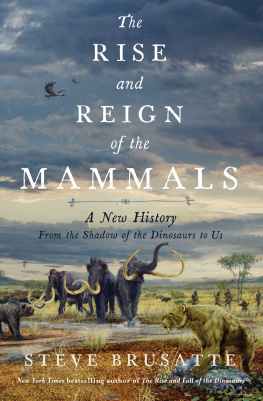

The main reason Im writing this, however, is to set the mammal story straight. You might think you know where mammals come from, but I reckon youll be surprised. If you thought it all began with the extinction of the non-bird dinosaurs, think again. If you believed mammals we fur-ball milk-givers merely scooted underfoot like terrified snacks for most of the time of the dinosaurs, you are dead wrong. If you have always repeated the tale that mammals come from reptile stock, wash your mouth out. We mammals are a lineage all our own. Our branch stretches away from the others, tied through time by our anatomy and physiology to the first backboned animals on land. Long ago we struck out in a flowerless Eden, and we made good.

I want to show you the parts of our mammal journey youve never seen before. Its impossible for me to introduce you to every animal, group, place and researcher in the history of mammals neither would you enjoy it if I did. Instead, Ive selected a smorgasbord of the tastiest morsels. Ill showcase astonishing fossil discoveries, the key twists and turns in mammal evolution, and a few of the many talented researchers who have transformed our knowledge. There are some stand-out characters you should meet, and localities to tour. I especially want to invite you to Scotland, and show you how our discoveries among the seaweed of the Western Isles fit into a global picture of mammal development, linking to mind-blowing new fossils recovered from places like China and South Africa.

Next page