In a far and distant time, there was once an explorer who heard legends of a nearby mountain with natural riches so vast that it could make his town the wealthiest in the world. With his townspeoples encouragement, he took off to search for the mountain but returned months later with the disappointing news that although he found the mountain, it was arid.

Everyone forgot about the mountain eventuallyall but one person who, led by a nagging feeling that there must be some truth to the legend, left the town in search of the great mountain. When this second explorer returned, she stunned everyone by reporting that the mountain was, after all, covered in lush vegetation, towering trees, and at least a few hundred species of plants.

In confusion, the townspeople began to incriminate one another. They accused the first explorer of plotting with neighboring towns. The second explorers integrity was also called into question. However, both explorers were telling the truth; they had just viewed the mountain from different positions.

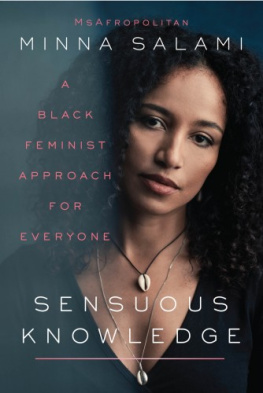

Working as a black, African-heritage woman in the white- and male-dominated world of ideas, I am like the second explorer who has navigated the other side of the metaphorical mountain. If the universal conceptsknowledge, power, beautyin this book represent the mountain, I have written about them from the second explorers perspective, in this case, an Africa-centered black feminist angle rather than the Eurocentric and patriarchalwhat I shall refer to throughout the book as Europatriarchalperspective from which we are accustomed to viewing them.

My primary motivation in writing from an Africa-centered black feminist perspective is, however, not to battle with the Europatriarchal view. It is not my aim to convince the first explorer that hes wrong about the mountain. That would place him, yet again, at the center of the narrative. What is important to me is the second explorers hidden narrative, to put her world at the center.

I emphasize the word hidden because it is also not the point of Sensuous Knowledge to provide a new or alternative perspective to the Europatriarchal one. That would also center whiteness and maleness by implying that they are the axis around which everything else must turn. My blackness and femaleness are not new or alternative angles to me. They are the only angles that I know as far as race and gender are concerned.

Also, while blackness and womanhood are qualities that make me intrinsically understand oppression and prejudice, they do not automatically put me in the position of the victim, just as every white- and male-born person is not automatically an oppressor.

Ethnicity, gender, and race are chance factors that nonetheless, thanks to the narratives that shape society, greatly affect how we view the world and how the world views us.

I would not swap a comprehension of how reality is connected to these narratives for an illusion that I live in a color-blind, postfeminist, postracial, and meritocratic fantasy world. As the irreplaceable Toni Morrison once wrote when addressing the naivete that white women have historically been afforded by virtue of being looked after by women of other ethnic backgrounds, Black women have always considered themselves superior to white women. Not racially superior, just superior in terms of their ability to function healthily in the world.

What she meant with these provocative words is that even if black womanhood can make life more challenging, to be a black woman is nevertheless a blessing, not least because it reduces the risk of a naive and ambivalent attitude to reality.

And so what is important about the explorers hidden view is that it disrupts one-dimensional thinking and contributes to a more vibrant understanding of the world. Black feminists have always stressed that feminist discourses need to be anticapitalist and anti-imperialist, capitalism being a profit-centered system and imperialism the means through which the obsession with growth and profit is satisfied. There is no point in smashing the patriarchy, as many Western feminisms claim to do, without fighting imperialism and capitalism. After all, there are no diamonds in European soil. There is no coltan in the USA. The resources that strengthen Western patriarchies are mostly unethically sourced from the Global South.

Fundamentally, patriarchal rule has also modeled systems of oppression on the violation of the environment. Developing a view of feminism as one in which humanity and nature live in a reciprocal relationship is a pressing task in the twenty-first century.

The Western feminist movement is, however, not monolithic, and Sensuous Knowledge draws inspiration from the international womens movement including figures such as the socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, ecofeminist Marie Mies, and the many Western activist groups from the Suffragettes to Womens Liberation to Me Too.

Although rooted in black feminism, Sensuous Knowledge speaks to the disaffected mood of the present time and is relevant to anyone who believes that the current Europatriarchal ruling systems are toxic and that we must develop paradigms of thought that instead are enlivening.

To rethink ideas that are central to the human mind with an Africa-centered black feminist sensibility is not to essentialize the ways that African, black, or female identities have been othered by a Europatriarchal value system. Instead, it is to unearth the subjectivity in these identities because, constructed as they may be, they shape our lives and so it is important to develop language and knowledge that works for and not against those excluded from the privileges of the status quo.

We may speak about knowledge as though it were a neutral termas though the male perspective on beauty were the same as the female perspective. Or as though power could possibly mean the same thing to black people as a group as it does to white people as a group. And sure, knowledge itself is neither female nor male, black nor white. But because we typically interpret knowledge production with a white and male bias, women and men and people of different races and ethnicities relate to it differently. To quote Morrison again, Narrative is one of the ways in which knowledge is organized.

The narrative through which we view knowledge is both the seed and the fruit of the culture it produces. To produce nourishing fruit, we need to plant sublime seeds.

And yet we typically try to cultivate a richer harvest with the same old weeds. We impose male norms on womens lives and the American Dream on every society. We raise girls so that they will grow up to become more like men but not boys to become more like women. We have to wonder why, despite all the feminist work, womanhood is still so devalued. Why do women still become annoyed when they are told (usually by men) that they are behaving like women? Conversely, why do they take pride in being told that they are behaving like men? Striving to become like men and adopt notions of masculinity is, frankly, setting a low bar. Men are just as enslaved by the social systemone that they hesitate to criticize because it amplifies an illusion about who they are. In fact, men are troubled with frustrated desires; they are caught up in the competitiveness of the rat race; they are sexually needy; they suffer from suicidal inclinations in disturbing numbers; and they possess an insatiable urge for power. Both women and men ought to reject the imprisoning definition of masculinity.

Im not saying that men arent privileged by these illusions of power. Precisely because of how power is defined, to be born male is to be born into a system that sees ones biological sex as superior to any other. But men are victims of what we can call the Superman syndrome, which is a cognitive dissonance that makes them erroneously believe that because the bars of their prison cell are golden, it is no longer a prison. The golden prison of masculinity sentences men to a life of conformity.