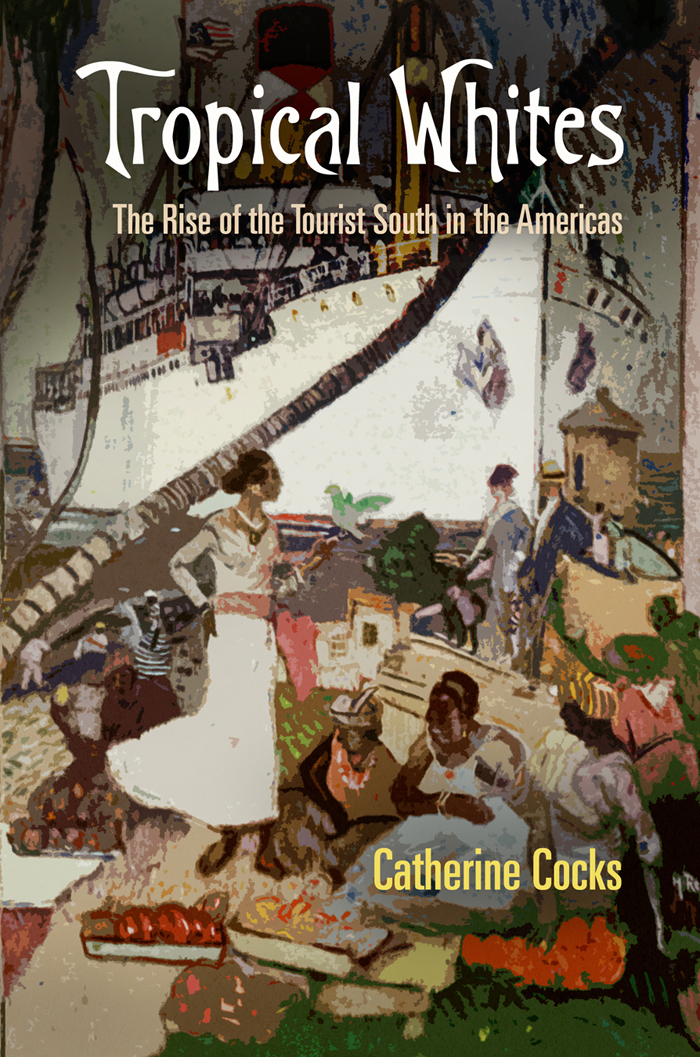

Tropical Whites

NATURE AND CULTURE IN AMERICA

Marguerite S. Shaffer, Series Editor

Volumes in the series explore the intersections between the construction of cultural meaning and the history of human interaction with the natural world. The series is meant to highlight the complex relationship between nature and culture and provide a distinct position for interdisciplinary scholarship that brings together environmental and cultural history.

Tropical Whites

The Rise of the Tourist South in the Americas

Catherine Cocks

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

copyright 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cocks, Catherine

Tropical whites: the rise of the tourist south in the Americas /

Catherine Cooks.1st ed.

p. cm.(Nature and culture in America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4499-1 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. TourismTropicsHistory19th century. 2. TourismTropicsHistory20th century. 3. AmericansTropicsHistory19th century. 4. AmericansTropicsHistory20th century. 5. Race relationsTropicsHistory19th century. 6. Race relationsTropicsHistory20th century. 1. Title.

G155.T73C64 2013

338.47918093dc 23

2012048416

For HanleyA NOTE ON AMERICA AND AMERICANS

Throughout this book, I use American to describe people and things from the Western Hemisphereall of it. When I mean people and things from the United States, I use the adjective U.S. or some similar locution. In a book that is about the travels of people from the United States in other areas of the Americas, using American to mean of the United States would be confusing as well as arrogant. Not following the customary usage, in contrast, underscores one of the central points of my argument: that tourism helped to constitute and formalize national differences at the end of the centuries-long colonization of the Western Hemisphere.

All translations are mine unless otherwise noted.

Introduction

Was there ever such a change? asked Ida Starr, steaming south from New York City to the Caribbean and feeling as serene and happy as a woman in a white linen frock can feel. She was not alone in her pleasure: Every one must have gone down into every ones trunk this morning to find white attire suitable for the warming temperatures. Travelers going south in winter at the turn of the twentieth century almost all changed into lightweight white clothing as the air warmed and the sun strengthened. On the third day of a Panama Mail cruise from San Francisco to New York, all the officers appear in white duck trousers. Another day and their blue uniform coats give way to white. Among the passengers, white flannel trousers vie with linen knickers among the men. The women... dazzle the ship with the sheerest of white summer things. Advertisements and illustrations for travel articles about the tropics regularly placed white-clad tourists in colorful market scenes. Even the ships carrying northern travelers into tropical waters were painted white, and the United Fruit Company dubbed its Caribbean passenger line the Great White Fleet upon its launch in 1899.

The temptation to dismiss this change of clothing as a trivial performance of high society etiquetteonly in summer did the fashionable wear whitemay be powerful. Hard on the heels of that reflex judgment may come the belief that whites wore white in the tropics in a defensive doubling of their pale-skinned privilege. Both of these analyses contain considerable truth, but they do not shed much light on what southward travel, ritually marked by the donning of white apparel, meant and why its popularity grew rapidly at the turn of the twentieth century. Because North Americans and Europeans believed that climate was one of the chief influences shaping their characters, travelers change of dress was far more than mere convention, a shield against contamination by the dark fecundity of the tropics, or even a practical response to the rising temperatures.

Donning sheer, snowy garments, northerners opened themselves to

The story of how such Faustian bargains became unnecessaryhow whites learned to love the tropics without losing their soulsis the subject of this book. Tropical Whites sketches the American history of the development of the global tourist south, or what I call the Southland, drawing on sources from Florida, Southern California, Mexico, and the Caribbean. In 1880, most European and North American whites regarded the tropics as the white mans grave; by the early 1940s, everyone knew that they constituted the most ideal winter resorts for vacationers from the temperate zones. This about-face required a significant rearticulation of popular beliefs about the relationship between the environment and human bodies, a rearticulation that diminished natures power to shape humanity and enhanced humanitys power to manage nature for its own benefit. Such a reweighting of the balance necessarily entailed changes in the way that North American whites conceived of human variation, especially the distinctions that constituted race and sexuality. In other words, the historical shift usually understood as the emergence of a modern society, one characterized by cultural pluralism and moral liberalization, owed much to the tourist industrys production of tropical whitescivilized, pale-skinned people with the youthful, sensuous joy of dark-skinned primitives.

Tropicality

Readers may protest that Southern California, Florida, and northern Mexico are not in the tropics. Indeed, these places do not lie between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, or 23 26 22 north and south of the equator. Nor do Bermuda and most of the Bahamas, which also figure in this history. And although Mexicos central plateau and Jamaicas Blue Mountains do lie between those lines, they are cooled by their lofty altitude. But travel writers, boosters, and diarists readily labeled these placesor at least some of their featuresas tropical. At the closing of the summer resorts in the northeastern and midwestern United States, Travel magazine reported in 1901, Many eyes turn to the sunny South, to far away Hawaii or tropical California; a column on travel books in the same magazine spoke of a brochure published by the Florida East Coast Railroad that featured photographic reproductions of the tropical charms of the state. Writing to his sister during his first visit to Florida in January 1880, John Gilpin reported that we have been here now a day and a half and are beginning to feel established tho every hour develops something new and strange in this tropical land.