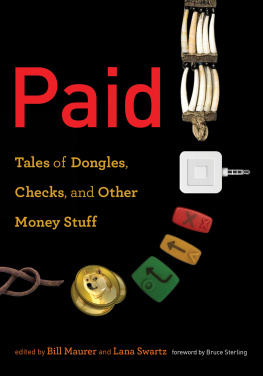

Paid

Infrastructures Series

edited by Geoffrey C. Bowker and Paul N. Edwards

Paul N. Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming

Lawrence M. Busch, Standards: Recipes for Reality

Lisa Gitelman, ed., Raw Data Is an Oxymoron

Finn Brunton, Spam: A Shadow History of the Internet

Nil Disco and Eda Kranakis, eds., Cosmopolitan Commons: Sharing Resources and Risks across Borders

Casper Bruun Jensen and Brit Ross Winthereik, Monitoring Movements in Development Aid: Recursive Partnerships and Infrastructures

James Leach and Lee Wilson, eds., Subversion, Conversion, Development: Cross-Cultural Knowledge Exchange and the Politics of Design

Olga Kuchinskaya, The Politics of Invisibility: Public Knowledge about Radiation Health Effects after Chernobyl

Ashley Carse, Beyond the Big Ditch: Politics, Ecology, and Infrastructure at the Panama Canal

Alexander Klose, translated by Charles Marcrum II, The Container Principle: How a Box Changes the Way We Think

Eric T. Meyer and Ralph Schroeder, Knowledge Machines: Digital Transformations of the Sciences and Humanities

Geoffrey C. Bowker, Stefan Timmermans, Adele E. Clarke, and Ellen Balka, eds., Boundary Objects and Beyond: Working with Leigh Star

Clifford Siskin, System: The Shape of Knowledge from the Enlightenment

Bill Maurer and Lana Swartz, eds., Paid: Tales of Dongles, Checks, and Other Money Stuff

Paid

Tales of Dongles,

Checks , and Other

Money Stuff

edited by Bill Maurer and Lana Swartz

foreword by Bruce Sterling

THE MIT PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

LONDON, ENGLAND

2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Maurer, Bill, 1968- editor. | Swartz, Lana.

Title: Paid : tales of dongles, checks, and other money stuff / edited by Bill

Maurer and Lana Swartz ; foreword by Bruce Sterling.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, [2017] | Series: Infrastructures |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028477 | ISBN 9780262035750 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Money--History. | Electronic funds transfers. | Automated

tellers. | Telematics.

Classification: LCC HG231 .M58655 2017 | DDC 332.4--dc23 LC record

available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028477

EPUB Version 1.0

Contents

Bruce Sterling

Bill Maurer and Lana Swartz

Scott Mainwaring

Lisa Servon

Lynn H. Gamble

David L. Stearns

Taylor C. Nelms

Sarah Jeong

Gary Urton

Lana Swartz

Alexandra Lippman

Bill Maurer

David Graeber

Maria Bezaitis

Whitney Anne Trettien

Julien Mailland

Jane I. Guyer

Bernardo Btiz-Lazo

Keith Hart

Michael Palm

Rachel ODwyer

Finn Brunton

Foreword

Dead Money

Foreword

Foreword

Bruce Sterling

I was charmed by this book. Its chock-full of wonder and sadness.

Im a novelist, but also an amateur historian of media. In my historical studies, I look for data with page-turning qualities, something eye-catching, marvelous, and maybe grotesque. Something that offers a high Cahill Factor, with the quirky and scarcely credible qualities of the legendary Thaddeus Cahills Telharmonium.

Cahills Telharmonium, you see, was once a gigantic, sophisticated electronic music production and distribution system. It debuted in 1906. Mark Twain was a happy subscriber to Mr. Cahills commercial music-streaming service. The Telharmonium was the technical state of the art for Gilded Age Manhattan. Millions of dollars were wasted on this grandiose device. A mastodon in a tar pit couldnt have died a more horrid and lingering death than this brilliant yet utterly doomed network machine. Ive never yet written a work of fiction about Cahills Telharmonium, but since I know something about it, I can write books with heartfelt, melancholy titles such as Gothic High-Tech.

The Cahill Telharmonium, however, for all its merits, was never nearly so vast, so all encompassing, so ambitious, so horrible, so dinosaurian as obsolete money systems. This book is all about archaic systems of financial exchange.

Its not a book about the fine hobby of numismatics, for metal coins, as physical objects, are romantic and pretty. Its about the debris that are paper checks, bills, tickets, stubs, files, records, logs, accounts, and receipts, or magnetic stripe cards, dongles, Minitel units, and defunct ATM Bancomatsa huge variety of money management technologies, but, well, theyre all trash. Nobody mulls them over with the severe joy that collectors experience with their Roman imperial coinage and obscure French postage stamps. This dead financial hardware is disgusting rubbish, even pollution.

They were once of severe and painful valuethe burden of a mortgage can kill you; a check that bounces is a lasting humiliationbut their worth on earth is brief, while their condition as junk is lastingly abject.

I surmise that this is why so many of the authors in this book feel a need to apologize for their keen interest in the topics they so entertainingly describe. This book is chockablock with technical wonderment. Who knew, for instance, that Benjamin Franklin printed fallen leaves into colonial American money because all-natural leaves are so hard for human beings to counterfeit? Who knew that the wife of Kwame Nkrumah kept a secret stash of Egyptian cash, robbed from her palace in an African coup dtat? But behind these bright sparks of historic erudition is a lasting air of mortal weltschmerz.

Why have we done such awful things to ourselves, just for our all-too-mortal systems of money? Take the Native Americans of California, for instance. These fortunate people were living in an area of nigh-utopian natural wealth and beauty, so its startling, and also depressing, to learn that these early inhabitants invested brutal effort and weird ingenuity in scraping and grinding coin-like tokens from pretty Californian seashells. Not only were these wampum-like strings of shell beads of critical importance to their own hunter-gatherer society, but they seemed to have no trouble at all exporting this system of value to everyone they could reach. They were the Silicon Valley of seashells as money.

People believe in money. But it just doesnt last.

To judge by our modern ingenuity in storing money, shipping money, and repeatedly wrecking our society with vicious financial panics, nobodys ever believed in money quite like we moderns do. What was once merely the root of all evil is now the root of our every whirring data packet. Its a grim tale, and yet this fine book conveys a heartening sense of memento mori. This too will pass. All too soon, the dismal banking systems that pester us nearly to madness will be as corny and archaic as the French Minitel, whose national saga, deftly touched on herein, is even sadder than an dith Piaf song.