Text 2017 University of Alaska Press

Published by

University of Alaska Press

P.O. Box 756240

Fairbanks, AK 99775-6240

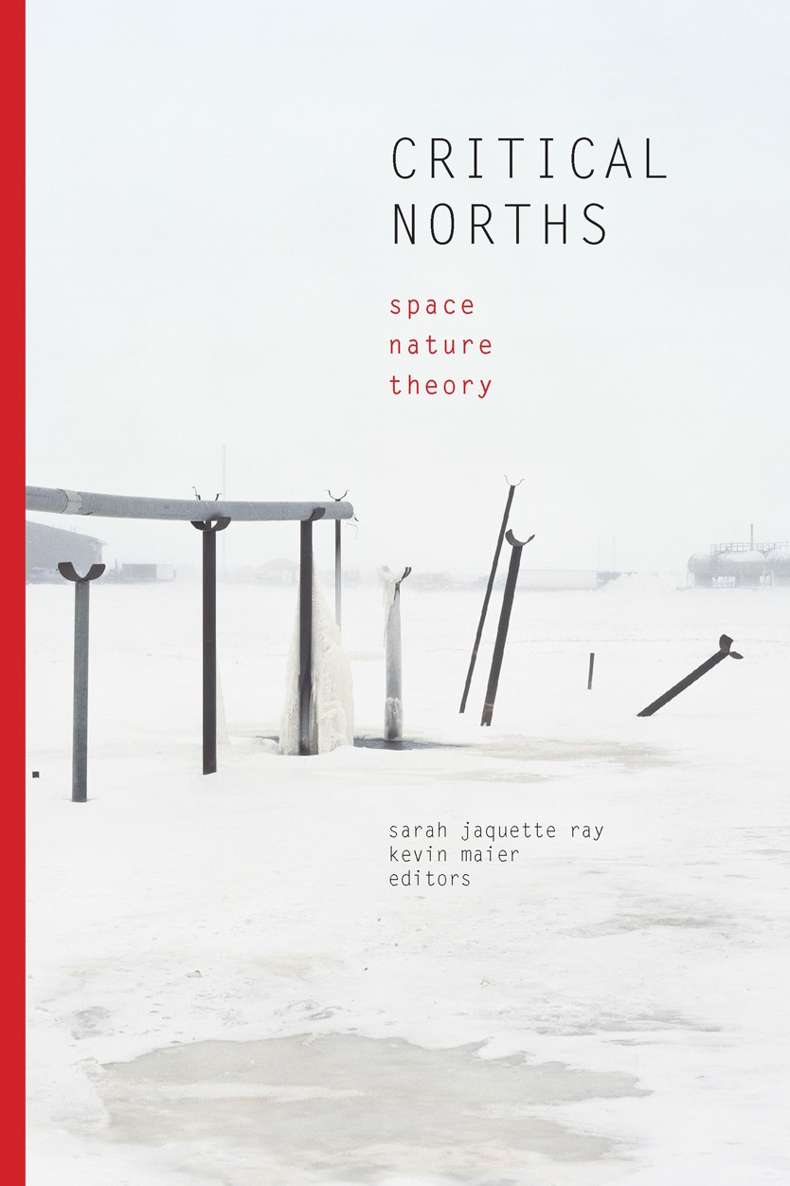

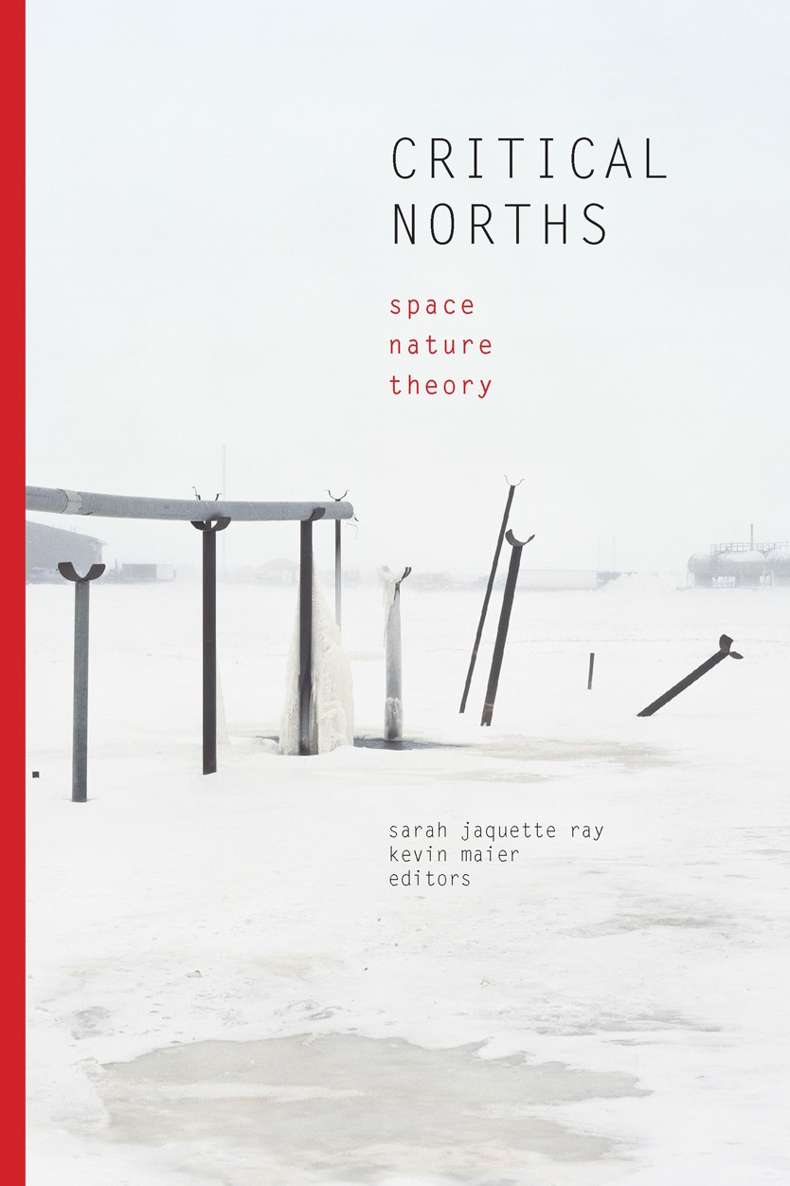

Cover design: University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks

Cover image: Broken pipe in Deadhorse, Alaska. From The Last Road North by Ben Huff.

Interior design: Rachel Fudge

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ray, Sarah Jaquette, editor. | Maier, Kevin, editor.

Title: Critical norths : space, nature, theory / edited by Sarah Jaquette Ray and Kevin Maier.

Description: Fairbanks, AK : University of Alaska Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026148 (print) | LCCN 2016045179 (ebook) | ISBN 9781602233195 (paperback) | ISBN 9781602233201 ()

Subjects: LCSH: Arctic regionsEnvironmental conditions. | Climatic changesArctic regions. | Indigenous peoplesArctic regions. | Human ecologyArctic regions. | North (The concept) | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Anthropology / General. | NATURE / General.

Classification: LCC GE160.A68 C75 2017 (print) | LCC GE160.A68 (ebook) | DDC 304.20911/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026148

Acknowledgments

CRITICAL NORTHS WAS INSPIRED BY AN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF Literature and Environment (ASLE) symposium Environment, Culture, and Place in a Rapidly Changing North, held at the University of Alaska Southeast in 2012. We would like to thank ASLE, especially managing director Amy McIntyre and then-president Joni Adamson; John Pugh, who was the chancellor at the University of Alaska Southeast; and Alison Krein, Virginia Berg, and Margaret Rea, our administrative support at UAS. They all enthusiastically supported the symposium in funding, time, website updates, program design, on-the-ground implementation, and genuine investment in this event and intellectual project.

The conversations held at that symposium precipitated many collaborations and projects, and so we would like to share the achievement of this books publication with all those who attended, spoke, and volunteered. We are indebted to our keynote presenters for shaping our discussions: Julie Cruikshank, Ernestine Hayes, Nancy Lord, and Ellen Frankenstein. In the spring semester leading up to the June symposium, we co-taught an upper-division undergraduate course and were inspired and awed by the students, who helped plan, orchestrate, and implement the symposium, in addition to contributing their own research as presenters. Their myriad commitmentsfrom volunteering at the registration table to leading tours to catering the salmon bake to hosting guestsmade hosting the symposium easier for us, but mostly it merged our research and teaching lives in meaningful ways.

The work of producing a book is mostly invisible to us scholars, so it is our pleasure to name the stalwart advocates of this project at the University of Alaska Press: James Engelhardt, Amy Simpson, Krista West, Rachel Fudge, and the Editorial Board. Eric Heyne deserves special recognition for his thorough reviews of the manuscript at multiple stages; thanks also to the blind peer reviewers for their thoughtful suggestions.

Thanks to photographer Ben Huff for the cover image. To us, the ironic hope suggested by the decrepit pipeline raises ambivalence about the petro infrastructure and gestures toward a central rhetorical goal of this volume. Huff evokes the irony in finding a landscape beautiful through the oil-shaped perspective of a windshield, or from the point of view of a road, a perspective we hope this volume elicits throughout. The line of the pipe also hints at the tensions between seeing the North as wilderness and seeing the North as resource. Finally, twenty-first-century pipelines inevitably highlight the transnational connections we raise in this book.

And thanks especially to the contributors who patiently responded to peer review, bent their disciplinary styles to fit this transdisciplinary project, and generally inspired us with their work.

Sarah Jaquette Ray and Kevin Maier

Introduction

Approaching Critical Northern Issues Critically

sarah jaquette ray and kevin maier

THE NORTH HOLDS A POWERFUL AND OFTEN PARADOXICAL PLACE in the Western imaginary. As a region, it is often seen as simultaneously empty of life and full of promise, the home of indigenous communities yet utterly conquerable, pristine and desolate yet marked by a long human history, and isolated from the problems of civilization while at the same time the stage for a planets climate drama. Symbolically, the North as resource has justified explorations both scientific and colonial, and continues to attract prospectors and adventurers in search of escape, transcendence, and fortune.

We see these northern notions in such popular texts and cultural productions as the Discovery Channels suite of shows set in the North, including Alaska: The Last Frontier and Deadliest Catch, and the 2007 film Into the Wild. Literary icons like Jack London, John Muir, and Farley Mowat have immortalized the North as a space of (white) exploration, adventure, and natural wonder. Meanwhile, indigenous perspectives of the North remain marginalized in these narratives, despite figuring heavily as central to the trope of a vanishing and noble landscape. Northern literary and cultural productions have contributed immensely to colonial narratives of indigeneity and nation.

Recently, the North has taken on profound environmental significance. Images of melting ice caps and starving polar bears as well as internationally publicized debates about the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) place the North at the center of discussions about the urgency of the planets environmental crisis. It is an indicator region for climate change. At stake are questions about developed nations right to consume, economic progress, animal protection, indigenous sovereignty, and various tragedies of the commons. This transnationalization of the North is one story about the North that revises dominant perceptions of the region as a barren, isolated backwater. Even Sarah Palin understood this new view of the North when she claimed international diplomacy expertise by pointing to the fact that Russia can be seen from land in Alaska (a point that comedian Tina Fey famously rephrased to I can see Russia from my house in a Saturday Night Live skit). While this sentiment did not have the desired effect of increasing Palins profile as a diplomat, it did exemplify a way of thinking about Alaska that those who dismiss her do not grasp.

This transnationalization of the North isnt necessarily a new story, of course, as battles over the Norths resources have long been waged via distant and diverse political and economic networks. When we add climate change to the equation, however, the scale of our contemporary environmental problems is simply greater, the consequences higher for everyonehere as well as from away (from the perspective of the North). The developing worlds desire for consumer electronics, rapid transportation, and constant high-speed connectivity have also upped the ante, as suggested by the slate of mineral extraction projects proposed, in development, and in production in the North. From the battle between corporations, nations, environmentalists, and First Nations communities over the tar sands in Alberta to the embattled Pebble Mine project proposed in the heart of key watersheds draining to Alaskas salmon-rich Bristol Bay to recent projections that the best places to live* in a climate-changed future will be in the North, the Norths visibility in the past several decades has decidedly been due to its nature(s).