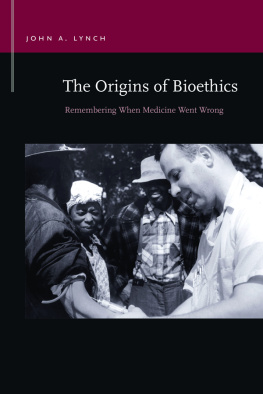

Foreword

James H. Jones

As a historian working on the Tuskegee syphilis experiment in the early 1970s, I had to make choices in my book about what I would emphasize. What would carry the narrative tale, what would become the backdrop? I knew as I wrote Bad Blood that there were other questions to explore, that other peoples sensibilities would broaden the scope of the inquiry. That is precisely what has happened.

The present volume, judiciously edited by Susan Reverby, provides its readers with a chance to see where this inquiry has gone. Beginning with a careful selection from several different archives of the letters between the Public Health Service and Tuskegee Institute, as well as other primary documents, it provides a glimpse into the mindset and decisions that made the study possible. Many of the other articles address differing ways to analyze the study. Some of these pieces do not always take an approach I would share; others even come to conclusions I abhor. But they do allow readers to see how the study has been understood and how differing values and beliefs shape historical understandings.

When I went to work on the Tuskegee Study in August of 1972, I was fresh out of graduate school. Several years earlier, I had worked on an unrelated topic in Record Group 90 of the PHS Records at the National Archives. These records pertained to the PHSs division of venereal diseases. Everything in the Record Group spoke either to the treatment or the prophylaxis of venereal disease, with one exception: four letter boxes of materials containing the records of an untreated syphilis program in Macon County, Alabama, in and around the county seat of Tuskegee. I remember spending two or three hours perusing these materials and being horrified by what I read. Still, I had seen other examples in my archival research of nontherapeutic medical research studies and I had no way of knowing that the Tuskegee Study was still active. I was, after all, in an archive.

James H. Jones holds the Alumni Distinguished Professor Chair and is professor of history at the University of Arkansas and the author of Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Printed by permission of James H. Jones.

When the Associated Presss Jean Heller broke the story of Tuskegee in July 1972, I had just completed my doctorate at Indiana University and was about to begin postdoctoral study in the history of medicine and medical ethics at Harvard University. I had been granted a fellowship to work on the social hygiene movement. Haunted by what I had read in those four boxes three years earlier, I decided to switch to the Tuskegee Study. The result, nine years later, was my book, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, A Tragedy of Race and Medicine.

In Bad Blood, I set several tasks for myself. At the broadest level, I wanted to discover what had happened and to shape the story into a coherent narrative that would reach a broad audience. But I also knew that there were important analytic points that needed to be made. First and foremost, I wanted to examine the role of race in medicine. Specifically, I sought to learn how racial attitudes affected the perception of disease that white physicians brought to their African American patients, and, having done so, I wanted to learn how those attitudes altered the ways in which white physicians responded to disease in the black community. At this point, scholars had taught us a great deal about race and politics, race and social structure, and race and the economy. But we knew very little about the relationship between race and medicine. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, I was convinced, was a critical case that could help to fill this lacuna.

Other concerns also informed my analysis. The Tuskegee Study lasted for forty years, making it the longest nontherapeutic experiment in history. Given this longevity, I was convinced that the study could teach us a great deal about the evolution of normative ethics within the medical profession, as well as the nature of decision making in bureaucracies. Moreover, I assumed that the physicians who conducted the study did not see themselves as evil agents who meant to do harm. I believed that the study could shed light on how good people could err for what many of them thought were the best of reasons. By pursuing Tuskegee, then, I hoped to learn about moral ambiguity, slippery slopes, and, in the end, moral catastrophe.

Tuskegees Truths provides a way to see how the study can be approached from many disciplines. Historians may bemoan the incursions made by others into their turf. But historical experiences have always been fair game. It is often in this disciplinary poaching that we gain new insights into the meanings that scholars or writers can make of a historical experience. By including a wide range of materials, from poetry, to plays, to medical accounts, Susan Reverby has tapped into the various ways the Tuskegee Study continues to have contemporary resonance.

What has impressed me the most about the Tuskegee Study is its staying power as a subject of public concern. We know that knowledge about the study circulates continually among many members of the African American community. The presidential apology, the film