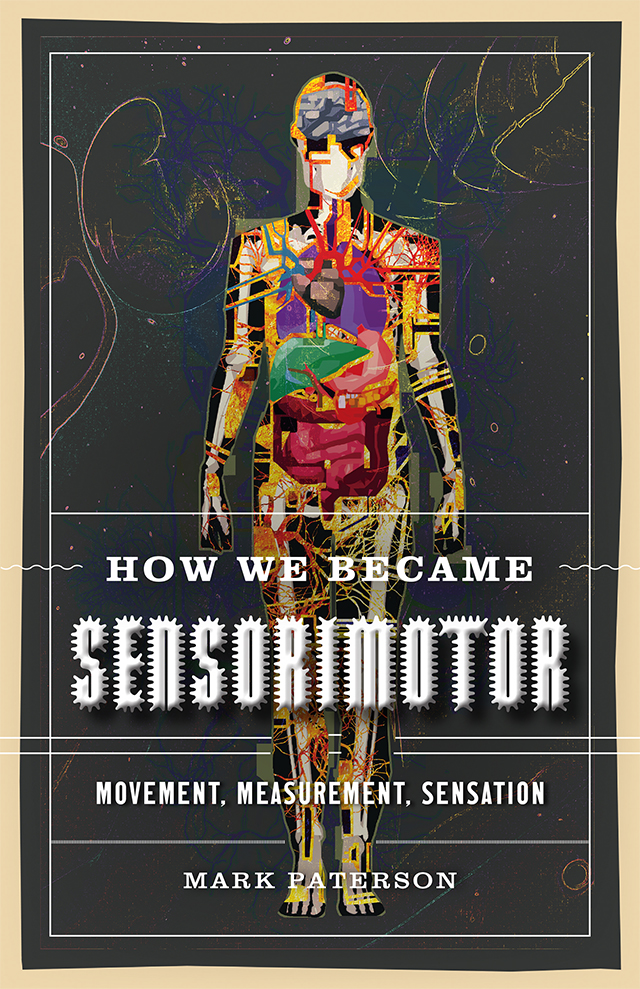

Mark Paterson - How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation

Here you can read online Mark Paterson - How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: U of Minnesota Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation

- Author:

- Publisher:U of Minnesota Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mark Paterson: author's other books

Who wrote How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Mark Paterson

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

Chapter 2 was published in a different form as On Pain as a Distinct Sensation: Mapping Intensities, Affects, and Difference in Interior States, Body and Society 25, no. 3 (2019): 10035; copyright 2019 SAGE Publications; reprinted with permission. Portions of chapter 3 were published in Architecture of Sensation: Affect, Motility, and the Oculomotor, Body and Society 23, no. 1 (2017): 335; copyright 2017 SAGE Publications; reprinted with permission. Portions of chapter 6 were published in Motricit, Physiology, and Modernity in Phenomenology of Perception, in Understanding Merleau-Ponty, Understanding Modernism, ed. Ariane Mildenberg, 17084 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019); reprinted with permission of Bloomsbury Academic.

Copyright 2021 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

ISBN 978-1-4529-6438-6 (ebook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021921945

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

Unlike sight or hearing, where a single identifiable organ is associated with that sense, we are less certain of the various kinds of sensation that arise within the bodily interior. As the founder of psychophysics Gustav Fechner put it in 1860: Objective sensations, such as sensations of light and sound, are those that can be referred to the presence of a source external to the sensory organ, whereas changes of the common sensations, such as pain, pleasure, hunger, and thirst, can, however, be felt only as conditions of our own bodies (1966, 15). A decade earlier, the physician and psychologist Ernst Heinrich Weber had initially bundled these sensations together as common sensibilities (Gemeingefhl) in his Der Tastsinn und das Gemeingefhl (1851, translated as On the Sense of Touch and Common Sensibility, 1978). Webers work on the physiology and psychology of touch inspired Fechners work to rigorously identify, differentiate, and measure sensations such as touch and pain using specially adapted instruments and devices. As the century progressed, an upsurge of interest in experimental physiology and the beginnings of experimental psychology further focused attention to bodily interiority, including the so-called muscle sense, fatigue, balance, and the bodys sense of movement and its position in space, bringing together diverse areas of scientific expertise from figures such as Wilhelm Wundt and his idea of muscular sensation, Charles Bells proposal of a muscle sense, Ernst Machs analyses of sensations and movement, and Charles Sherringtons coinage of proprio-ception (the sense of bodily position in space).

As this book will show, the scientific work of the identification and measurement of somatic sensations necessitated an inventiveness not only in the building of specialized instruments and apparatus for empirical research, but also in the conceptual framework, inevitably leading to shifts in terminology between time periods and disciplinary areas. Empirical and conceptual work in this area surges between 1833 and 1945, and includes those early sensory experiments in psychology and psychophysics (by Weber and Fechner in Germany), but also physiology (Sherrington in Britain), neurology (Gordon Head and Henry Holmes in Britain, Kurt Goldstein in Germany), and neurosurgery (the mapping of the human motor cortex by Wilder Penfield in Canada); and the tracking of animal and human locomotion through chronophotography (Eadweard Muybridge in the United States, tienne-Jules Marey in France), the measurement of fatigue in the laboratory and then the factory (Angelo Mosso in Italy, Jules Amar in France), and a return to the very idea of movement, the physiological concept of motricity, within embodied consciousness (Maurice Merleau-Ponty in France, who explicitly adopts Head and Holmess idea of body schema in 1945). Accordingly, each chapter focuses upon a particular thematic related to bodily sensation, including the muscle sense, pain, fatigue, balance, proprioception, and the philosophical uptake of the physiological concept of motricity. Each chapter engages with the corresponding scientific background, including the design and application of specialized measuring instruments. Successively, a picture of how these scientific discoveries informed new approaches to the body emerges.

Fast-forward to the near-present. In his last few months of office, President Obama made a highly publicized tour of the United States to celebrate the countrys progress in science, medicine, and technology. On October 13, 2016, Obama visited Pittsburgh as part of this White House Frontiers tour and shook the robotic hand of a wheelchair-using paraplegic named Nathan Copeland. Copeland had lost the use of both arms and both legs after a car accident left him with spinal cord damage as a teenager in 2004. A brain implant developed through DARPAs (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) Revolutionizing Prosthetics program, along with National Science Foundation funding, allows Copeland not only to control the movement of his robotic prosthesis but also to regain a sense of touch, to feel objects and people interacting with his artificial hand. This was all part of the part of the BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) initiative, previously announced by Obama with great fanfare and a $100 million budget in 2013. Obama, clearly enjoying himself and aware of the TV news cameras, turned the robotic handshake into a fist bump, and then said impulsively, Lets blow it up! Both mimicked exploding fingers, one with his human hand and the other with a robotic one. Obama turned to the gathered crowd and asked rhetorically: Does everyone fully grasp whats going on here? (Alba 2016).

The act of grasping is indeed the key. Obama explained to the audience that Copeland was not only directing his robotic hand through conscious intention, but also receiving feedback on his own hands position in space and its resistance to objects. Previous configurations of robotic prostheses had allowed object manipulation, but without this feedback, often experienced as a component of touch, movements are slow and imprecise. To test whether Copeland actually registered the tactile feedback correctly, researchers blindfolded him and then touched each of the fingers of the robotic right hand (see Figure 1). Each time, Copeland correctly identified the location. As the Washington Post reported at the time, Copeland said: I can feel just about every finger. Sometimes it feels electrical, and sometimes its pressure, but for the most part, I can tell most of the fingers with definite precision. It feels like my fingers are getting touched or pushed (Nutt 2016). These words show the difference between the touch involved in grasping and the more familiar ideas of cutaneous touch, or sensations on the skin. Scientists call the self-perception of bodily position in space proprioception, coined by the physiologist Charles Sherrington in 1906, and it is a necessary but uncelebrated component of our everyday somatic experience, as I discuss in chapter 1. In extremely rare cases of neurological disorders, proprioception is lost completely, and Oliver Sackss (1986) case study of Christina, The Disembodied Lady, and Jonathan Coles (1995) account of I.W. (Ian Waterman) both show the extraordinary consequences of having to learn how to move and walk again, maintaining control of limbs only through constant visual scanning and with great mental effort and concentration.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation»

Look at similar books to How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How We Became Sensorimotor: Movement, Measurement, Sensation and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.