For BJS and LJS

Contents

When we met, Eliza was twenty-four and had just moved in with her then boyfriend, and Haley was twenty-two and quite literally chasing a man across Europe. Things quickly got personal; over our first lunch date, Haley asked if there were wedding bells in Elizas future, a question Eliza preferred to avoid. Meanwhile, Eliza suspected that Haleys feverish pursuit had far more to do with her own history than any true love connection (spoiler alert: she was right).

Over the eight years since, weve traveled across the country together, celebrated several Friendsgivings, and attended important life events as plus-ones. Weve advised each other on health-care plans, impulse buys, haircuts, and questionable apartment features of all kinds (shout-out to Elizas bathroom with a cramped stall that resembled an industrial freezer more than a shower).

And though our respective relationship statuses have changed, our own bond hasnt faltered. Neither has our interrogation of singlehood. Through it all, weve asked each otherlate at night, first thing in the morning, holidays and birthdays especiallywhat will our lives look like if one or both of us never marry? If neither of us ever has children?

Eliza eventually became so obsessed by these questions that she designed an English course for college first-years on the rhetoric of singlehood. Every semester, she began by explaining why she used the word singlehood rather than the more colloquial singledom. The suffix called to mind other inevitable life stageschildhood, adulthoodimplying that being single was not a lesser kingdom to which spinsters were exiled but a phase of life that each of us inhabits for an indeterminate length of time, entering and exiting at intervals, occasionally straddling the line.

Some students were more skeptical of the subject than others. One young woman in particular, who quickly identified herself as a feminist, challenged Eliza from the back row. She felt the course devalued marriage. Eliza thought of herself at her students age: engaged, grieving a miscarriage, sleeping in her car between classes to avoid the peers who stared openly at her ring.

Thats not my intention, Eliza assured her student. The point is to value the options.

Eliza had spent the better part of a decade sifting through those options: as a twenty-year-old divorce starting over in a new city, a twenty-six-year-old leaving behind a perfectly suitable partner for no other reason than she felt she must, a stubbornly independent twenty-nine-year-old so intent on self-sufficiency that she refused to ask close friends for even a brief ride to the airport.

And so, Eliza led her students onward: screening clips from Bridget Joness Diary, Insecure, and Queer Eye; questioning the romantic motivations in action movies and the differences between being alone and being lonely. She graded more than one paper on the oeuvre of Taylor Swift.

Up next on the syllabus was a twentieth-century throwback.

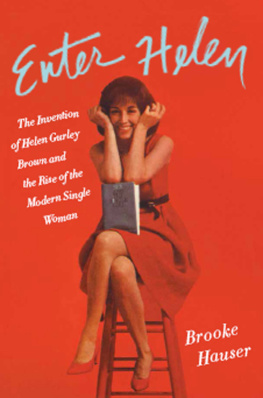

On May 23, 1962, Helen Gurley Browns Sex and the Single Girlthe unmarried womans guide to men, careers, the apartment, diet, fashion, money and meninnocuously appeared on bookshelves, its plain teal cover and simple serif type in no way hinting at the brazen sex positivity within. Helens publisher had changed the title from Sex for the Single Girl to Sex and the Single Girlanything to smooth over the vulgarity of unmarried, sexually active women. (Of course, this was well before Helen, as editor in chief of Cosmopolitan, began running now-signature, then-scandalous headlines like What to Do with (and to) a Sexually Selfish Man.)

That slim volume went on to sell two million copies in its first three weeks. It would be creditedamong other texts, most notably Betty Friedans The Feminine Mystique, which was published a year laterwith sparking second-wave feminism.

Only a few pages in, Eliza texted Haley: You have to read this.

Haley didnt miss a beat in buying her own copy. (We take each others recommendations with the utmost gravity; no one but Haley couldve convinced Eliza to watch CW teen classic The Vampire Diaries.) As predicted, Haley flew through the book, tearing up at its closing note: You, my friend, if you work at it, can be envied the rich, full life possible for the single woman today. Its a good show... enjoy it from wherever you are, whether its two in the balcony or one on the aisledont miss any of it.

Helens parting words deeply resonated with Haley. In her twenties, Haleys mom had been a voice-over agent regularly grabbing cocktails with 1987s brightest upcoming talents. And then the switch, as she calls it, got flipped: she wanted a baby with the hunger previously reserved for her career.

And so, the family lore of how Haleys mother decidedor rather, felt compelledto become pregnant framed it as the ultimate choice without choice, a gripping need that a younger Haley feared would one day overtake her, too. She remembers sitting in her adolescent bedroom wondering how much time she had left before her goals of writing and editing in New York City morphed into daydreams of nursery dcor and keeping time by her biological clock.

Motherhood, it seemed, was an inevitability.

But now, at thirty, Haley is acutely aware that her switch hasnt been flipped. In fact, with each passing day, not only does she expect that innate stirring less and less, but more and more shes questioning why motherhood was framed this way: not as a path sometimes taken after weighing ones options, but as a desire that all women experience and are consumed by, rendering the process of deliberation moot.

However, she did end up getting engagedthough it didnt involve bended knee or compulsory answer. It was a months-long conversation that had more to do with finances and the plan if one of them died (romantic!) than it did with booking a venue for a Saturday wedding in June. The most surprising part of the proposal wasnt the question; rather, it was how there was really no question at all. She and her partner made a decision about their futuretogether.

And so, the end of her own singlehood era is probably what sent Haleys chin quivering at the close of Helens bookthough she had more than a few gripes with the manifestos so-called feminist rhetoric that Eliza was also eager to dissect. It couldnt be ignored or glossed over: Helen was a complicated figure, and like all feminist icons, an imperfect one.

Originally pitched as a single girls guide to having an affair (which in 1962 parlance just meant having sex), Helens decidedly gleeful advice encompassed pursuing men (Men like sports; can you afford not to?), getting ahead at work, spending money, cultivating sexiness (Good health is sexy. Tired girls are tiring!), styling ones apartment, hosting parties, and cleaving to absurdly elaborate beauty regimens.

With Sex and the Single Girl, Helen launched her very particular brand of singlehood, one that told women their unmarried years could be too rewarding to rush out of while simultaneously handing them a laundry list of ways to land a husband. Still, like us, Helen seemed to conceive of singlehood as an era, and she wanted women to revel in theirs, including but not limited to enjoying sex. Her radical stance paved the way for narratives like Murphy Brown, Living Single, and Sex and the City.

For the time, Helens book was damningly provocative. Friedan wasnt alone in describing it as obscene and horrible, and reading it today can evoke similar responses. Not only does Sex and the Single Girl contain messages that feel woefully outdatedsuch as eliciting expensive gifts from powerful men in the workplacebut Helens language is also at times racist, homophobic, fatphobic, classist, and ableist. Her recommendations for a life well lived fail to acknowledge her own significant privileges as a cisgender, straight, able-bodied white woman with a wealthy husband and lucrative professional connections.