The Age of Longevity

The Age of Longevity

Reimagining Tomorrow for Our New Long Lives

Rosalind C. Barnett and Caryl Rivers

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barnett, Rosalind C., author. | Rivers, Caryl, author.

Title: The age of longevity : reimagining tomorrow for our new long lives / Rosalind C. Barnett and Caryl Rivers.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016009086 (print) | LCCN 2016016851 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442255272 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781442255289 (Electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: LongevitySocial aspects. | Population agingSocial aspects. | Older peopleSocial conditions. | Civilization, Modern21st centuryForecasting.

Classification: LCC HQ1061 .B366 2016 (print) | LCC HQ1061 (ebook) | DDC 305.26dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016009086

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To my husband Nat, my children, Amy and Jonathan, and my grandchildren, Reuben and Tess. May they use their long lives to realize their dreams.

RCB

To my children, Steve and Alyssa, my grandchildren, Lauren, Zuey, and Azalea, and to my great-granddaughter, Tinsley Alan. And to the memory of Alan Lupo, my husband, soulmate, and best friend.

CR

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to our agent, Joelle Delbourgo, and our editor, Suzanne Staszak-Silva, for all their help and support.

Thanks to the Brandeis Womens Studies Research Center and its director, Shulamit Reinharz, and the centers student-scholar partnership program. We benefited greatly from the enthusiasm and hard work of these undergraduates:

Ellie Driscoll

Clara Gray

Elana Horowitz

Alexandra Libstag

Kiana Nwaobia

Carolyn Rogers

Thanks also to the support of the Harvard Institute for Learning in Retirement (HILR), whose director, Leonie Gordon, helped with an online survey, and to Jim Johns, who worked with us to fine-tune the survey and analyze the data. And to the hundreds of HILR members who completed the survey.

Also, for their continuing support and encouragement, thanks to Dean Tom Fiedler of the Boston University College of Communication and its journalism chairman, Bill McKeen.

Several people generously gave their time to read and review our chapters. Thanks to Ruth Nemzoff, Jacqueline James, and Erlene Rosowsky.

Finally, thanks to professor Sandra Cha of the Brandeis International Business School for inviting us to share some of the books material with one of her graduate classes.

Chapter 1

Reimagining Tomorrow

Those of us alive today will be the longest-lived generation in history. Lengthy and productive lives are not the privilege of our great-grandchildren, but the probable destiny of most of us.

The 20th century gave us roughly 20 years of additional life expectancy. A 5-year-old born in 1900 could anticipate living 55 years. By 2006, that figure had jumped to 73.3 years!

These advances will continue. Over the past half century, every forecast of how long people will live has fallen short. Despite fears that obesity, global warming, failure of antibiotics, and pandemics would reverse this trend, life expectancy in rich countries has grown steadily, by about 2.5 years a decade, or 15 minutes every hour.

What will we do with these extra years? Thats the question we need to answer. The changes to come will be sweeping, ranging from our tiny cells to our social institutions to our everyday lives. The gift of the 21st century will be increasing the quality of these added years.

For the first time in history, the timing of predictable decline is being challenged. Shakespeares seven ages of man runs from helpless infancy to helpless old age. No one in the bards time could imagine changing this scenarioand until recently, no one else could either.

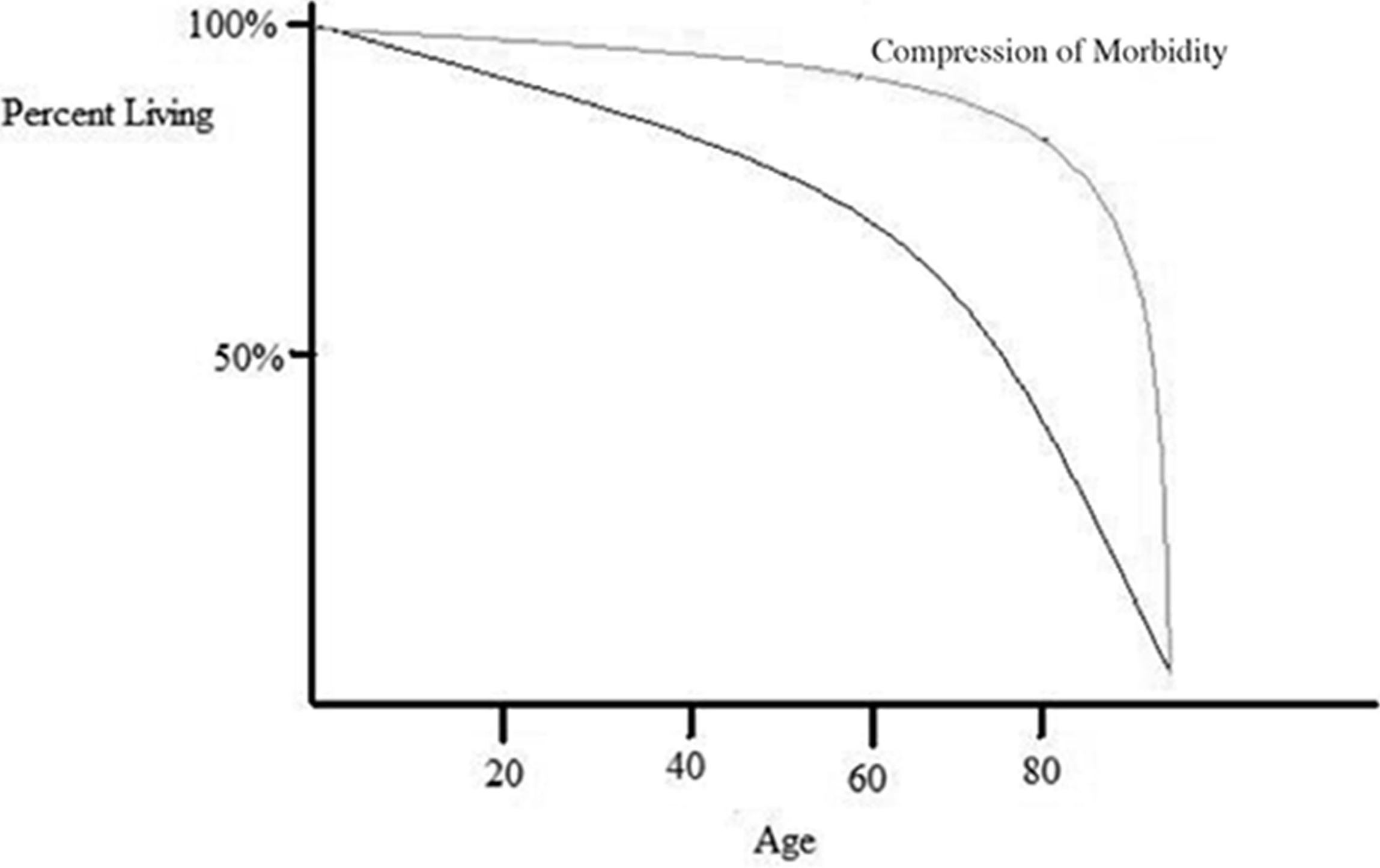

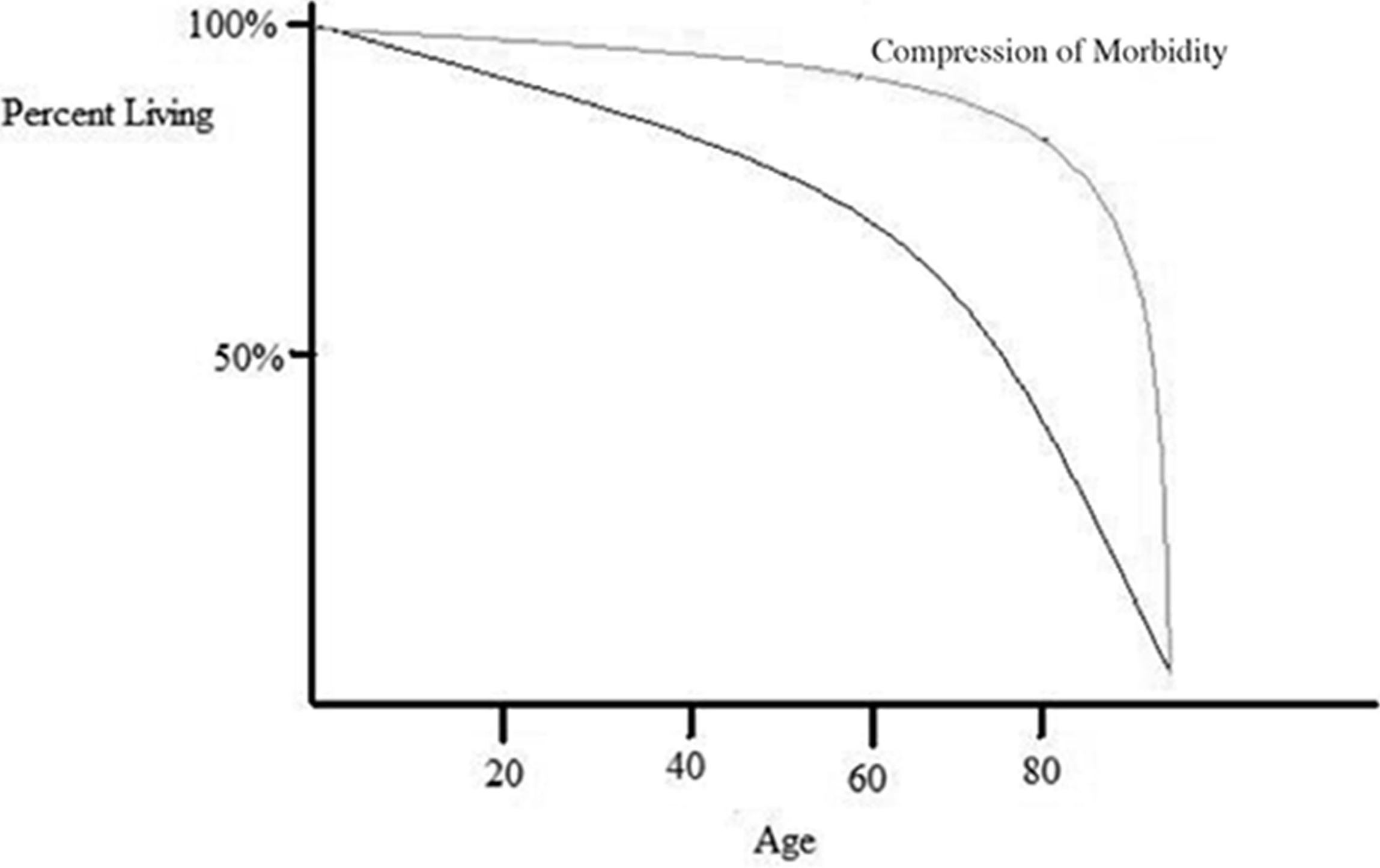

Of course, we all eventually wear out; we all die. But thanks to galloping advances in science and technology, decline is occurring much later in life and will be even steeper than it is today, as seen in the graph in figure 1.1. So, we will have many years of productive living before confronting end-of-life issues.

In the past century, we eradicated or defanged many of the killers of childrenpolio, whooping cough, influenza, scarlet fever, smallpox, TB, measles, cholera, and so on. Today, nearly 100 percent of American children survive to age 15. In this century, we will surely see a similar story about the killers of the older adult years. We already see signs that the years ahead will be as different from what has gone before as today is from 1915. Back then, test tube babies, flights to the moon, penicillin, heart transplants, blade runner limbs, and the conquest of childhood diseases would have been thought impossible fantasies.

The Shape of Things to Come

People are living longer; for some that is a scary scenario. The media in particular spin grim tales of steady slow declines that make a long life a nightmare instead of a gift. Pessimists regard this as a horrifying trend, sure to bankrupt Social Security and Medical School reports that adult vigor can be extended well into the ninth decade of life, with illness and disability compressed into a period that shortly precedes death.

Compression of Morbidity.

Fries calls this phenomenon compression of morbidity. His research finds that if the age at the onset of the first chronic infirmity can be postponed, then the lifetime illness burden may be compressed into a shorter period of time. The idea behind compression of morbidity is to squeeze or compress the time horizon between the onset of chronic illness or disability and the time in which a person dies.

In other words, if you suffer major illnesses later rather than earlier in life, you will spend fewer years in decline, and sickness will occur nearer to the age of your death. Medical technology is rapidly finding answers for serious health conditions that occur early in life.

Professor S. Jay Olshansky of the University of Illinois at Chicago says, The modern rise in life expectancy is one of humanitys crowning achievements, and he notes that compression of death has been squeezed into a fairly narrow region between the ages of sixty-five and ninety.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.