Also by Dr. Robin R. Meyers

To the faculty, staff, and administration of Oklahoma City University, for giving me students to teach, and the freedom to teach them. To the beloved members of Mayflower Congregational UCC Church, for restoring my faith in organized religion. To my mother and father, for their legacy of love and language. To Bill Moyers, for his friendship and encouragement. And to Bruce Tracy at Doubleday, for believing in this book.

Introduction

The premise of this book is that most of us are working frantically to secure the good life, while expending the only life we have in the process. We put off living until the living is good, only to discover that we never learned how to live in the first place.

Theres a lot of talk these days about slowing down, simplifying, returning to Walden Pond, but I dont see it happening. Thoreau makes a great artifact for the coffee table, but in real life people seem to be moving faster and faster and enjoying their lives less and less.

Oddly, just as we seem to be on the verge of discovering a Unified Theory of Creation, we appear to be no closer to a Unified Theory of Living. While scientists are discovering the interconnectedness of everything in nature, the business of life itself still seems hopelessly fragmented: work is more punishment than vocation (Monday symbolizes tedium, while Friday stands for liberation); play is some form of indulgence that never quite satisfies; and meanwhile we pass each other in the halls, making plans for the perfect vacation.

In short, we serve time in search of real time and never quite grasp the fact that now is as real as it gets. Life happens while we wait for something to happen, and so its no wonder that when we get there nothing seems to be happening!

Our problem, now as always, is that we pass life by in search of it. We decide in advance which moments are worthwhile, and which are ordinary, and thus we stifle the very movement of the spirit that we seek. Because we view simple things as mundane. its no wonder that most of the time we are bored. Constantly reminded that sophisticated people do sophisticated things and simple people do simple things, we end up feeling sorry for our simple selves most of the time.

If the Beautiful People are doing decadent things in the south of France, who are we to suggest that watching the moon rise or rocking a baby is better than the party? If someone is bungee-jumping into the Royal Gorge, who are we to say that ironing a shirt, or sipping coffee, or breathing in the fragrant cheek of a child is somehow more satisfying, even if it is less thrilling?

What we need, more than anything, is not just to sing the song (Simplify Life), but to learn the dance. We need suggestions, concrete and sensible prescriptions for living the simple and sacramental life. Weve heard all about how good this would be for us. Now we need to talk about how to do it.

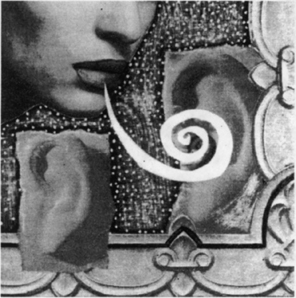

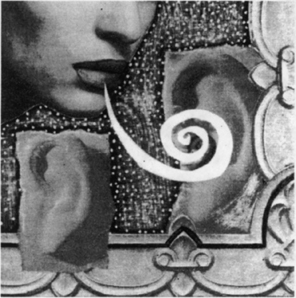

This book intends to provide just such practical advice. It is both a rationale for the simple life and a menu of sorts, a dozen homilies on a dozen lost arts of living. Its a book about the moment, and about all the seemingly insignificant things occurring every day that are worthy of worship. Its about hearing again, in a culture that has gone deaf. Its about seeing again, in a culture that is blinded. Its about feeling again, in a culture that overstimulates and thus numbs itself.

Ever mindful that happiness is a by-product, as John Stuart Mill reminded us, this is a book about how to be happy without really trying and about how to make ones home into a temple, regardless of the decor. It is written in the hope that some of the tenderness of childhood remains in all of us, long after childish fear and cruelty have been outgrown. Its a simple book, about simple truth and the simple living that brings it to light. As the twentieth century winds down and a new millennium dawns, human beings need to move forward, but not by leaving the best of themselves behind.

I

The Lost Art

of Conversation

Expression is the one

fundamental sacrament.

Alfred North Whitehead

Every morning, as our infant son lies cooing in his crib, we make sure that he hears his name before he sees our faces. Cass Cass Isaac, we call out in a drawn and almost forlorn tone of voice. His cooing stops. He hears a familiar sound. If we hide around the corner out of sight, his eyes grow bright, but he doesnt make a sound. Without a face to watch, all his energy goes to listening. The adults are making noises again, he thinks. Vibrations that name me, and prove that I exist, have traveled across the air from Someplace Else and into my fuzzy and not-well-focused world.

This may not sound like much, but it is the essential human transaction. We speak the world into beingit is linguistically constituted, as Heidegger would say, because humans are Homo loquins (speaking animals). The whole of our civilization and sophistication depends on language. In the poetry of Genesis, God speaks the world into being, saying. Let there be light. In the prologue to Johns Gospel, Jesus is the linguistic incarnation, Gods best word, which became flesh and dwelt among us full of grace and peace.

The story of the Tower of Babel is meant to show that when language fails, human communication and, therefore, cooperation are impossible. These days, the tragedy is not confusion, but silencepeople moving, ghostlike, in glass houses against which no one dares to throw the stone of a word.

Consider our little boy again. He is learning not only that human beings make sounds to reach out to one another, but that a face will follow the soundbecause the world is acoustical cause and effect. Its the ear that welcomes the footsteps of the world. The dog barks, the thunder rolls, the screen door bangs out its hyphenated greeting. Sound is a messenger, and an interpreter.

Long before our culture opted for the visual over the auditory; it was an acoustical highway that God traveled: in the ear of the prophet, in the narrative of the water well, in the ringing simplicity of the Sermon on the Mount. To live the simple, sacramental life again, we must put conversation back where it belongs: at the center of human life.