Contents

Guide

Breakfast

with the

Centenarians

First published in Italy in 2017 as A spasso con i centenari by Il Saggiatore, Milan.

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2019

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Daniela Mari, 2017

Translation Copyright Denise Muir, 2019

The moral right of Daniela Mari to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Denise Muir to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 483 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 484 9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

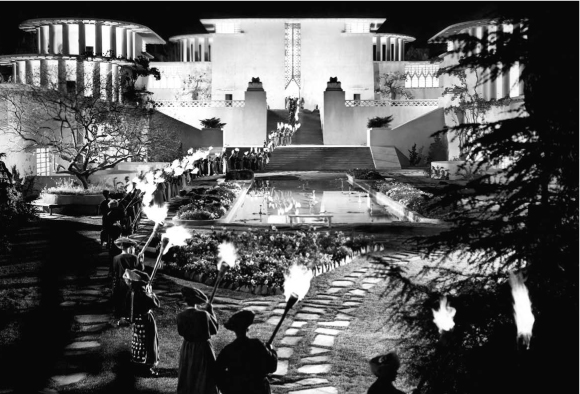

A still from Frank Capras 1937 movie Lost Horizon, which immortalized the fictional utopia Shangri-La ( Alamy).

CONTENTS

Introduction

What does ageing mean? Is it the inexorable passing of time until you catch sight of yourself in the mirror one day and dont recognize the person looking back? That moment in time when you realize the reflected you is no longer the way you see yourself in your head? But what time-spectrum are we talking about exactly? Is it the one that starts at birth but feels different as we progress through our twenties, forties, and into our sixties and beyond? Or is it the one thats shaped by individual biological and life experiences, meaning it can vary from person to person?

Ageing is a complex, dynamic and ultimately variable phenomenon. When I was younger, for example, and had to juggle family, work and study commitments, all at breakneck speed, I saw old age as a time when I would finally be able to start working my way through the stacks of books piled everywhere (the only true feature in my house), take that trip Id put off for years, enjoy lots of free time, and finally stop worrying about how I look. After many years spent studying ageing, I realize that the most common scientific definition the accumulation of changes in cells and tissues as we grow older, bringing about the increased risk of illness and death is oversimplified and refers purely to biological ageing.

The first time I met my publisher to discuss this book, in a pretty fish restaurant in the centre of Milan, near the university where I had taught for many years, he asked me why I had become a geriatrician. All of a sudden, the distant memory of myself as a young student flooded my consciousness, like perfume filling the air when the top is taken off. In the mid-1970s, geriatric medicine was not a compulsory part of the medical degree programme, merely a subsidiary exam. With the enthusiasm of youth, I thought Id be studying the secrets of ageing and would discover a new Shangri-La (the Tibetan valley that was home to a community of especially long-lived monks, described by novelist James Hilton in Lost Horizon (1933), which was later adapted for the big screen by Frank Capra). But a meeting in a hospital outside Milan with the lecturer I wanted to supervise my dissertation brought me back to reality with a bump: the hospital had only one tiny ward and scores of elderly patients, many lying in corridors. He was so busy providing patient care, not to mention exhausted due to staff shortages and a lack of funds, that he had no time for anything else. It was only many years after graduating, when I found myself studying the blood profiles of a group of ultra-long-lived individuals, that my interest in ageing was revived.

The thing that fascinated and surprised me the most was getting to know these grand old individuals and being able to explore the worlds theyd grown up in worlds so different to the one we know today. My work in the field has taught me that ageing is a complex phenomenon, and as such requires a humanistic approach if were to see beyond the purely biological. As my research progressed, the wider academic world also acknowledged that the demographics of the Western world had changed, as elderly adults accounted for an increasingly large chunk of the population. Geriatrics deals not only with the prevention and treatment of conditions afflicting the elderly, but also provides psychological, environmental and socioeconomic assistance. It is a discipline which is also known as gerontology (namely, the study of the biology, physiopathology and psychosocial aspects of ageing).

My experiences with older individuals and the clear need for more teaching staff in geriatrics were what made me want to be a geriatrician and choose gerontology as my field of study. It allowed me to focus both on teaching young people and on caring for the elderly. Breakfast with the Centenarians is the result of that decision, a choice I have never regretted.

Unsurprisingly, geriatrics is a fairly young area of study, given that we as a species have only recently been lucky enough to make it so far into old age. In the first chapter of this book, I try to convey just how fascinating the early studies of ageing were. Some of them even earned their authors a Nobel prize!

Like many of the myths surrounding the ageing process, to equate ageing with old age can be misleading ageing begins from conception, and the second chapter explores our first years on earth.

The care aspect of my profession cannot be viewed separately from the scientific observation and research part they are two sides of the same coin and their duality forms the backbone of this entire book, but in particular. It looks at the issue of cognitive decline, which is a major concern as we grow old. Spending time with the many patients I have treated over the years, each with their own past, has shown me that cognitive decline depends on the experiences people have throughout their lifetimes. Our job as clinicians is to explore these individual histories and suggest treatments which dont always have to be pharmacological. My own research delves into such experiences, primarily looking at the importance of art, music, culture and an active lifestyle in remaining healthy in old age.

The notion that lifestyle choices can substantially affect our ageing is one of the most exciting debates in current gerontological research, the objective now being to achieve what the World Health Organization calls active ageing. looks specifically at this aim. I delve into new and innovative technologies that can assist us in this regard: robotics, for instance, has made the leap from the realms of fantasy to the real world as a viable research and treatment tool.

Coming full circle, in the last chapter I return to my early experiences in gerontological research, to a time in the 1990s when I embarked on the study of successful ageing, as it was becoming known. Centenarians, of which there are more and more in society (due to increased life expectancy and better access to healthcare in infancy, childhood and adolescence) are an extraordinary model of humanity, and a compendium of the many ageing theories proposed over the centuries.